>

Analytics>

How sanctions are enforced in the United States: a multi-level mechanism of responsibilityHow sanctions are enforced in the United States: a multi-level mechanism of responsibility

Chapter I

Legal basis for sanctions in the US

In the United States, the legal basis for the application of sanctions is a special law, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or IEEPA, which grants the President special economic powers to respond to an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to national security, international politics, or the economy that originates in whole or in part from abroad (50 U.S.C. 1701(a)).

In order for the special powers regime to be triggered, the President must declare a national emergency, a "national emergency", with respect to the threat in question (50 U.S.C. 1701(b)).

In the case of the events of 2014 in Ukraine, this urgency was declared by the Executive Order of then-President Barack Obama of 6 March 2014 No.13660, and since then it has been renewed by subsequent executive orders (No.13661, No.13662, No.13685, No.13849, No.13883 and No.14065) and has not been terminated to date.

In general, the US sanctions system imposed in connection with the war in Ukraine includes three categories of sanctions:

Blocking of assets of individuals and legal subjects designated in accordance with Executive Orders No.13660, No.13661, No.13662 and No.13685. Executive Orders define broad categories of persons whose assets are subject to blocking, and the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) maintains a list of specific names and companies (the List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons, SDN List).

Sectoral sanctions against subjects operating in the sectors of the Russian economy designated by the Secretary of the Treasury pursuant to Executive Order 13662 and included in the Sectoral Sanctions Identification List (SSIList);

A ban on new investments and exports or imports of goods, technology or services to or from Crimea.

To implement Executive Orders, OFAC has issued a number of regulations, which are codified in Part 589 of Title 31 of the Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.).

The complete list of prohibited transactions is contained in paragraphs 31 C.F.R. §§ 589.201-209.

In particular, according to 31 C.F.R. § 589.201 (a):

“All property and interests in property that are in the United States, that come within the United States, or that are or come within the possession or control of any U.S. person of the following persons are blocked and may not be transferred, paid, exported, withdrawn, or otherwise used for any other purpose”.

In accordance with clause (b) of the same paragraph:

“The prohibitions in paragraph (a) of this section include prohibitions on the following transactions:

(1) The making of any contribution or provision of funds, goods, or services by, to, or for the benefit of any person whose property and interests in property are blocked pursuant to paragraph (a) of this section; and

(2) The receipt of any contribution or provision of funds, goods, or services from any person whose property and interests in property are blocked pursuant to paragraph (a) of this section”.

Paragraphs 31 C.F.R. §§ 589.202-205 contain restrictions with respect to sectoral sanctions targeting various sectors of the Russian economy (finance, energy, defense and oil production). In 31 C.F.R. §§ 589.206-208 prohibit investments in Crimea, as well as the export of goods, services, and technology to Crimea or their import from Crimea. Finally, paragraph 31 C.F.R. §§ 589.206-208 are devoted to prohibitions and strict conditions with respect to correspondent or payable-through accounts of foreign financial institutions that have knowingly facilitated certain significant transactions.

Chapter ІІ

Types of liability for sanctions violations

Liability for violation of sanctions imposed under IEEPA is provided for in 50 U.S.C. 1705(c):

“(a) Unlawful acts

It shall be unlawful for a person to violate, attempt to violate, conspire to violate, or cause a violation of any license, order, regulation, or prohibition issued under this chapter.

(b) Civil penalty

A civil penalty may be imposed on any person who commits an unlawful act described in subsection (a) in an amount not to exceed the greater of

(1) $250,000; or

(2) an amount that is twice the amount of the transaction that is the basis of the violation with respect to which the penalty is imposed.

(c) Criminal penalty

A person who willfully commits, willfully attempts to commit, or willfully conspires to commit, or aids or abets in the commission of, an unlawful act described in subsection (a) shall, upon conviction, be fined not more than $1,000,000, or if a natural person, may be imprisoned for not more than 20 years, or both”.

Thus, the sanctions regime in the United States is enforced at two levels - civil and criminal liability. Accordingly, the enforcement measures designed to ensure compliance with special restrictive measures are civil fines, criminal fines and imprisonment for individuals. In addition, there are two types of forfeiture - criminal forfeiture in personam (against a person) and civil forfeiture in rem (against property).

Criminal forfeiture relates to a specific person and requires a criminal indictment against such a person, issued in the framework of criminal proceedings. Criminal forfeiture is a punishment. Such confiscation is also provided for in Ukrainian law.

By contrast, civil forfeiture is not directed against the person who committed the crime, but against the property that was obtained through the crime or used to commit the crime. Unlike criminal forfeiture, there is no criminal conviction required, although the government is still required to prove in court by a preponderance of evidence that the property was linked to criminal activity. In a civil forfeiture case, the state is the plaintiff and the property itself is the defendant. This is the so-called “defendant in rem” (Defendant-In-Rem).

The procedure allows the court to bring together all those who have an interest in the property in one case and resolve all issues related to the property at one time. In a civil forfeiture case, the state is considered the defendant, and any person who claims an interest in the property is a claimant.

Civil forfeiture allows the government to bring cases against property that is not available for criminal forfeiture, such as property of criminals who are outside the United States, including terrorists and fugitives. Civil forfeiture also allows for the recovery of assets belonging to deceased defendants or in cases where the defendant cannot be identified.

Civil forfeiture is provided for in paragraph 981 of Chapter 46 of Title 18 of the United States Code.

Accordingly, this paragraph the following property is subject to forfeiture to the United States:

“(A)Any property, real or personal, involved in a transaction or attempted transaction in violation of section 1956, 1957 or 1960 of this title, or any property traceable to such property. [...]

(C)Any property, real or personal, which constitutes or is derived from proceeds traceable to a violation of section 215, 471, 472, 473, 474, 476, 477, 478, 479, 480, 481, 485, 486, 487, 488, 501, 502, 510, 542, 545, 656, 657, 670, 842, 844, 1005, 1006, 1007, 1014, 1028, 1029, 1030, 1032, or 1344 of this title or any offense constituting “specified unlawful activity” (as defined in section 1956(c)(7) of this title), or a conspiracy to commit such offense”.

The concept of “specified unlawful activity” mentioned in the section is formulated in such a way that it includes violations of the sanctions regime.

Chapter ІІІ

Level of civil liability: OFAC regulations and practice

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is responsible for the civil aspect of sanctions enforcement. It monitors compliance with sanctions restrictions and imposes civil penalties in case of violations of the sanctions regime. To this end, OFAC issues regulations that consolidate existing legislation on sanctions restrictions.

In accordance with these OFAC regulations (31 C.F.R. § 589.213):

“(a) Any transaction on or after the effective date that evades or avoids, has the purpose of evading or avoiding, causes a violation of, or attempts to violate any of the prohibitions set forth in this part is prohibited.

(b) Any conspiracy formed to violate the prohibitions set forth in this part is prohibited”.

For a more detailed explanation of this term, see 31 C.F.R. § 589.414:

“With respect to § 589.215, a prohibited facilitation or approval of a transaction by a foreign person occurs, among other instances, when a U.S. person:

(a) Alters its operating policies or procedures, or those of a foreign affiliate, to permit a foreign affiliate to accept or perform a specific contract, engagement, or transaction described in §§ 589.206 through 589.208 without the approval of the U.S. person, where such transaction previously required approval by the U.S. person and such transaction by the foreign affiliate would be prohibited by this part if performed directly by a U.S. person or from the United States;

(b) Refers to a foreign person purchase orders, requests for bids, or similar business opportunities involving a transaction described in §§ 589.206 through 589.208 to which the U.S. person could not directly respond as a result of the prohibitions contained in this part; or

(c) Changes the operating policies and procedures of a particular affiliate with the specific purpose of facilitating transactions that would be prohibited by this part if performed by a U.S. person or from the United States”.

In addition, OFAC has a special Economic Sanctions Enforcement Guidelines. The Guidelines, in particular, define how OFAC may respond to identified violations of the sanctions regime.

The list of possible administrative acts includes:

- No Action;

- Request Additional Information;

- Cautionary Letter;

- Finding of Violation;

- Civil Monetary Penalty;

- Criminal Referral;

- Other Administrative Actions.

The Guidance also contains a broad list of factors that OFAC takes into account when deciding which administrative act to apply and (in the case of a fine) what amount of fine to impose.

Among these factors:

- Willful or Reckless Violation of Law;

- Awareness of Conduct at Issue;

- Harm to Sanctions Program Objectives;

- Individual Characteristics;

- Compliance Program;

- Remedial Response;

- Cooperation with OFAC;

- Timing of apparent violation in relation to imposition of sanctions (e.g., one thing is when it happened as soon as the sanctions were imposed, and another is when the sanctions have been in effect for a long time);

- Other enforcement actions taken against the Subject Person;

- Future Compliance/Deterrence Effect;

- Other relevant factors on a case-by-case basis.

Each of these factors, depending on the situation, may turn into a mitigating or aggravating circumstance for the subject.

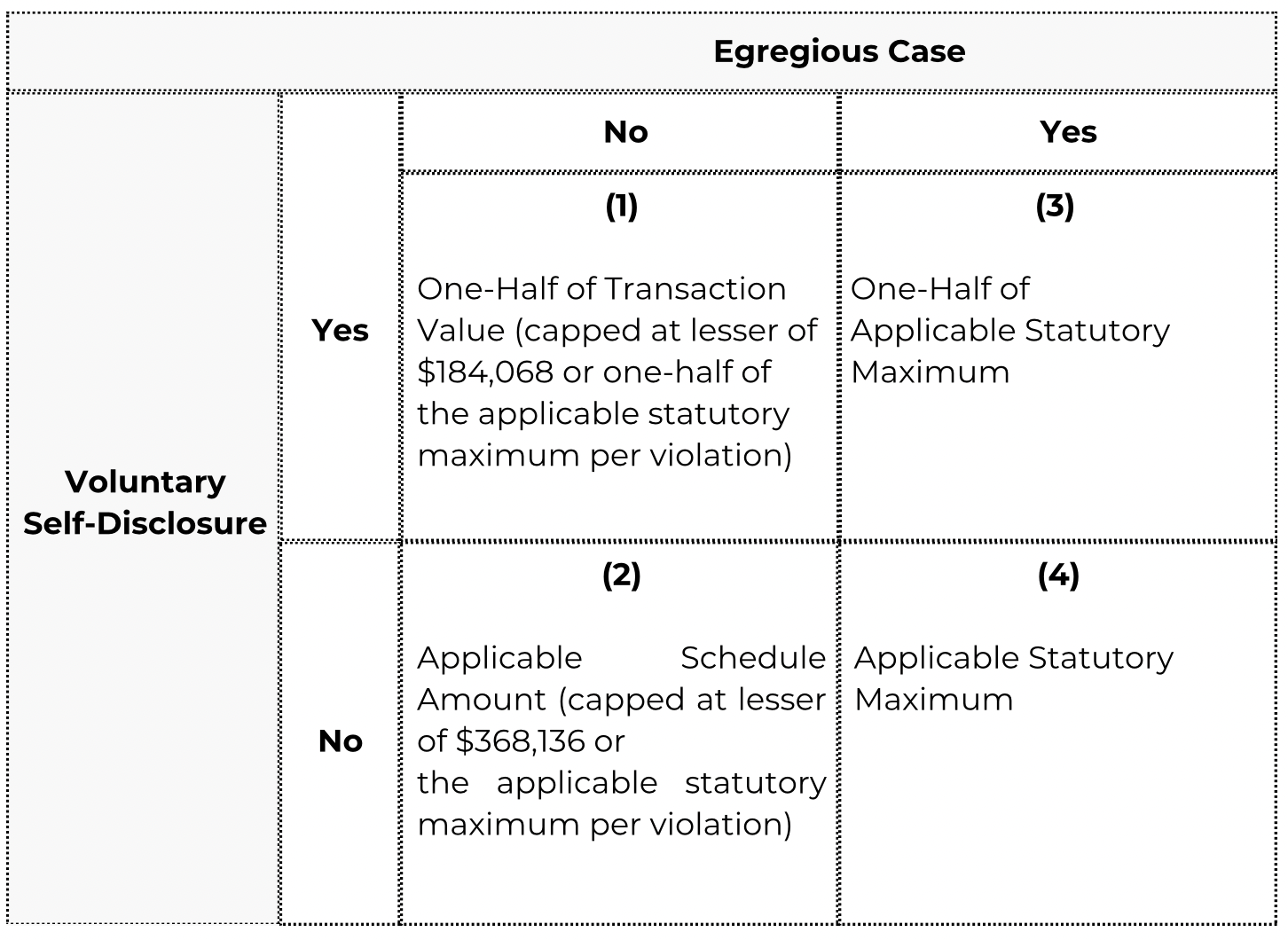

The Guidelines also provide a matrix for determining the maximum amount of a fine depending on a combination of two factors – the egregiousness of the violation and the availability of a voluntary notification of the violation by the subject itself.

In making the egregiousness determination, OFAC generally will give substantial weight to General Factors A (“willful or reckless violation of law”), B (“awareness of conduct at issue”), C (“harm to sanctions program objectives”) and D (“individual characteristics”), with particular emphasis on General Factors A and B. A case will be considered an “egregious case” where the analysis of the applicable General Factors, with a focus on those General Factors identified above, indicates that the case represents a particularly serious violation of the law calling for a strong enforcement response.

The Guidance also provides for the possibility of entering into agreements between OFAC and the subject being held accountable. And responsible subjects often enter into such agreements.

Chapter IV

Some OFAC cases

The case of the Binance crypto exchange

Binance Holdings, Ltd., a Cayman Islands-based virtual currency exchange with branches around the world, has agreed to pay $968,618,825 to settle its potential civil liability for 1,667,153 alleged violations of multiple sanctions programmes (including the Russia sanctions programme in connection with the war in Ukraine). For more than five years, from August 2017 to October 2022, Binance matched and executed virtual currency transactions on its online exchange platform between U.S. citizens and users from sanctioned jurisdictions or blocked persons. The total amount of transactions in violation of the sanctions restrictions was $706,068,127.

Buffalo Grove, Illinois-based financial services and payments company daVinci Payments (daVinci) has agreed to forfeit $206,213 to settle its potential civil liability for 12,391 alleged violations of OFAC sanctions relating to Crimea, Iran, Syria, and Cuba. Between 15 November 2017 and 27 July 2022, daVinci, which operates prepaid rewards card programmes, allowed the redemption of rewards cards from individuals who were residents of sanctioned jurisdictions. The settlement amount reflects OFAC's determination that daVinci's violations were not egregious and that the violations were voluntarily disclosed by the company.

Swedbank Latvia AS, a subsidiary of Swedbank AB, an international financial institution headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, has agreed to pay $3,430,900 to settle its potential civil liability for 386 alleged violations of OFAC sanctions relating to Crimea. Throughout 2015 and 2016, a Swedbank Latvia customer used Swedbank Latvia's e-banking platform from an IP address in Crimea to send payments to individuals in Crimea through US correspondent banks. The customer initiated 386 transactions totalling $3,312,120, which were conducted through US correspondent banks. The settlement amount reflects OFAC's determination that Swedbank Latvia's conduct was not egregious, although it was not voluntarily disclosed.

Poloniex, LLC, a Delaware company headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts, which operated an online trading and settlement platform, has agreed to pay $7,591,630 to settle its potential civil liability for 65,942 alleged violations of numerous sanctions programmes (including the Russia sanctions programme). Between January 2014 and November 2019, Poloniex's trading platform allowed customers believed to be located in sanctioned jurisdictions to engage in online transactions involving digital assets, including trades, deposits and withdrawals, with a total value of $15,335,349, despite having reason to know their location based on Know Your Customer information and Internet Protocol address data. The settlement reflects OFAC's determination that Poloniex's alleged violations were not voluntarily disclosed and were not egregious.

On behalf of itself and its subsidiaries, Microsoft Ireland Operations Ltd. and Microsoft Russia, Microsoft has agreed to pay $2,980,265.86 to settle its potential civil liability related to the export of services or software from the United States to jurisdictions subject to comprehensive sanctions and to sanctioned persons or blocked persons, in violation of the Cuba, Iran, Syria, and Russia sanctions programmes.

Between July 2012 and April 2019, Microsoft entities committed 1,339 alleged violations of multiple OFAC sanctions programmes by selling software licences, activating software licences and/or providing related services from servers and systems located in the United States and Ireland to sanctioned persons and other end users located in Cuba, Iran, Syria, Russia and Crimea. The total value of these sales and related services was $12,105,189.79.

The settlement amount reflects OFAC's determination that the conduct of Microsoft's entities was not egregious and was voluntarily disclosed, and reflects the significant remedial actions that Microsoft took after discovering the potential violations.

Chapter V

Level of criminal liability: the practice of the department of justice

The criminal aspect of sanctions is the responsibility of the US Department of Justice.

In addition, compliance with the sanctions regime in the United States is monitored, in particular, by the following agencies: The U.S. Department of the Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS).

FinCEN and BIS have published an Alert (see here and here) urging financial institutions to be vigilant against efforts by individuals or entities to evade export controls implemented in connection with the Russian Federation’s further invasion of Ukraine. This joint alert provides financial institutions with an overview of the current export restrictions, a list of commodities of concern for possible export control evasion, and select transactional and behavioral red flags to assist financial institutions in identifying suspicious transactions relating to possible export control evasion.

In March 2022, an interagency law enforcement task force was launch “Task Force KleptoCapture”. Its task is to ensure the sweeping sanctions, export restrictions, and economic countermeasures that the United States has imposed, along with allies and partners, in response to Russia’s unprovoked military invasion of Ukraine. In particular, as a result of the efforts of this team, the United States initiated a number of cases of sanctions violations, which resulted in fines and confiscation of property.

The initiation of a criminal case against a person on the relevant charges provides for the possibility of forfeiture of assets that qualify as proceeds of crime. This includes civil forfeiture in rem, i.e. forfeiture without a criminal indictment.

In December 2022, the United States passed the law that allows transferring to Ukraine the funds received from the sale of forfeited assets of sanctioned persons. According to this law, the Attorney General may transfer to the Secretary of State the proceeds of any covered forfeited property for use by the Secretary of State to provide assistance to Ukraine to remediate the harms of Russian aggression towards Ukraine. Any such transfer shall be considered foreign assistance under the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2151 et seq.), including for purposes of making available the administrative authorities and implementing the reporting requirements contained in that Act.

Chapter VI

Some criminal cases brought by the Department of Justice

The Malofeev case

The first case in the United States to test the mechanism of civil forfeiture (as part of criminal proceedings on charges of sanctions violation) with the subsequent transfer of funds to the needs of Ukraine was the case of Konstantin Malofeev (for more information on this case, see here).

In April 2022, a criminal case was opened in the United States against Russian oligarch, media mogul, founder of the Orthodox TV channel Tsargrad TV, Konstantin Malofeev. He is accused of violating sanctions imposed by the United States back in 2014, during the first stage of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

The indictment states that Malofeev, contrary to the established prohibitions, hired an American citizen, Jack Hanick, to work for Malofeev-owned TV companies in Russia and Greece, as well as to participate in the acquisition of a TV company in Bulgaria. In addition, Malofeev attempted to retroactivelyre-register his USD 10 million US investment to a shell company in order to circumvent the sanctions imposed on him. Simultaneously with the indictment, the prosecutor's office announced the confiscation of Malofeev's assets.

On 2 February 2023, the court granted the prosecutor's motion to confiscate Malofeev's US assets totalling USD 5.4 million.

District Judge Paul Gardephe (Manhattan Federal Court) allowed the prosecution to confiscate Malofeev's funds totalling $5.4 million. Malofeev did not appeal against the confiscation decision. The US Attorney General Merrick Garland said that the funds would be transferred to help Ukraine.

The case of the Amadea yacht

On 23 October 2023, the US Department of Justice filed a lawsuit in a federal court in New York to confiscate the $300 million Amadea superyacht, the beneficial owner of which is believed to be the sanctioned Russian oligarch Suleiman Kerimov.

KleptoCapture Task Force co-director Michael Khoo said in a statement that the decision to seize Amadea was made ‘after a thorough and painstaking effort to gather the necessary evidence to demonstrate Suleiman Kerimov's clear interest in Amadea and repeated abuse of the US financial system to support and maintain the yacht for his benefit’.

Between July and October 2021, Kerimov purchased Amadea through a company owned by Imperial Yachts President Yevgeny Kochman. All subsequent expenses for the maintenance of this yacht (maintenance, fuel, equipment, inspections and port dues, etc.), contrary to the sanctions restrictions, were made using US financial institutions or in favour of US resident companies. For the period from September 2021 to April 2022, such expenses amounted to approximately USD 1.3 million.

As Kerimov was under sanctions at the time of the purchase of the yacht, he was prohibited from making any payments to or receiving any services from US companies, as well as from using US financial institutions for the relevant transactions.

In addition to the two cases mentioned above, which have received wide media coverage, there are a large number of cases that, although little known to the general public, indicate the vigorous struggle of the US law enforcement system against violators of the sanctions regime. Here are just a few of them.

The case of Goltsev and others

At the end of October 2023, the US Department of Justice unveiled a criminal indictment against Nikolai Goltsev, Salimdzhon Nasriddinov and Kristina Puzyreva on conspiracy and other charges related to an international procurement scheme on behalf of Russian companies under sanctions. The defendants are accused of illegally exporting millions of dollars worth of semiconductors, integrated circuits and other dual-use electronic components to Russia through shell companies in Brooklyn. Some of the components supplied were found in Russian weapons and electronic intelligence equipment seized in Ukraine. The case implicates two Brooklyn-based companies, SH Brothers Inc. and SN Electronics Inc. who allegedly facilitated the scheme by sourcing, purchasing and delivering the prohibited items to sanctioned end users in Russia. The defendants, knowing of the potential military applications of the electronics, used intermediary corporations in various countries to divert the goods to Russia. The government is represented in this case by the National Security and Cybercrime Division, and the investigation was coordinated through the Disruptive Technology Strike Force and the KleptoCapture Task Force.

Igor Panchernikov, a former member of the US Armed Forces, was sentenced to 27 months in federal prison for conspiring to illegally export defence articles, including thermal imaging scopes and night vision goggles, to Russia without the required licence, in violation of the Arms Export Control Act.

Panchernikov, a former Air Force officer, pleaded guilty in March to conspiracy charges. The scheme, which operated from December 2016 to May 2018, involved accomplices purchasing defence goods from US online sellers, sending them to Panchnernikov, who would then mail them to Russia after checking and concealing them. Panchernikov used fictitious names of the senders, falsely identified the goods and hid them in other shipments to conceal the illegal exports. His accomplice, Yelena Shifrin, pleaded guilty, another defendant, Vladimir Prydacha, pleaded not guilty, and two are fugitives. The investigation involved the FBI offices in Los Angeles and Chicago, the US Postal Inspection Service, and the National Security Investigations Service.

The case of Orekhov and others

The US Department of Justice has unveiled an indictment charging Russian citizens Yuri Orekhov, Artem Uss, Svetlana Kuzurgasheva, Timofey Telegin and Sergey Tulyakov, as well as Juan Fernando Serrano Ponce and Juan Carlos Soto. They are accused of conspiring to illegally obtain US military technology and sanctioned Venezuelan oil through a complex scheme involving shell companies, cryptocurrency and illegal transactions. Orekhov and Kuzurgasheva, using Nord-Deutsche Industrieanlagenbau GmbH (NDA GmbH) as a front, allegedly obtained sensitive military technology from US manufacturers and smuggled hundreds of millions of barrels of oil from Venezuela to Russia and China. The indictment details a complex network of transactions, shell companies and falsified documents, including cryptocurrency transfers and large amounts of cash, for which the defendants face up to 30 years in prison if convicted. The investigation is being led by the FBI with the support of the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of International Affairs, the U.S. Department of Commerce and European law enforcement agencies.

The case of Romaniuk and others

According to court documents, Eriks Mamonovs and Vadim Ananits, Latvian nationals and CEOs of CNC Weld, along with Stanislav Romaniuk of Ukraine and others, are charged with conspiring to violate US export laws by attempting to smuggle a precision grinding machine from Connecticut to Russia. The machine, which is used in nuclear proliferation and defence programmes, required an export licence to Russia, which the defendants did not obtain. U.S. authorities, in cooperation with Latvian authorities, intercepted the grinding machine in Riga, Latvia, preventing it from being shipped to Russia. The indictment also includes charges against CNC Weld and BY Trade OU. Mamonov, Ananits and Uzbalis, who were arrested in Latvia, are awaiting extradition, while Romaniuk was arrested in Estonia in June 2022.

Conclusions

In response to Russia's unprovoked aggression against Ukraine, Western countries reacted with one voice by imposing unprecedentedly broad sanctions against the aggressor state. However, in order for the sanctions to be truly tangible for Russia and to really undermine its ability to wage war, an effective mechanism for enforcing the sanctions restrictions is needed, which would ensure severe and inevitable punishment for those who seek to circumvent or avoid these restrictions.

The mechanism that operates in the United States can serve as a model for other partner states and for Ukraine itself, which is most interested in the strength of its sanctions policy.

The US model of sanctions enforcement is multilayered: it includes both criminal and civil law levels. The criminal law level provides not only for the familiar fine as a measure of punishment and imprisonment for individuals, but also for the possibility of in rem (civil) forfeiture of assets related to criminal activity without a criminal indictment against the owner. The civil level, in turn, provides for an extensive and flexible system of fines that can significantly increase the state budget.

These legal mechanisms, or at least their individual elements, should be adopted by states seeking to vigorously combat sanctions evasion.

The Institute of Legislative Ideas is an independent think tank that studies the implementation of anti-corruption policy in Ukraine and its compliance with international anti-corruption standards. We analyze the asset recovery mechanism and explore the opportunities for its improvement and extension. Today, we consider it one of the primary tasks to ensure compensation for the damage caused by the Russian aggression against Ukraine at the expense of Russian assets.