>

Analytics>

Transposition of EU Directive 2024/1226 by EU Member States: Definition of Criminal Offences and Penalties for Violations of Union Restrictive MeasuresTransposition of EU Directive 2024/1226 by EU Member States: Definition of Criminal Offences and Penalties for Violations of Union Restrictive Measures

Publisher: think tank ‘Institute of Legislative Ideas’. All rights reserved

Authors: Andriy Klymosyuk, Mykola Rubashchenko, Oksana Huzii, Tetiana Khutor

The study is produced by NGO «Institute of Legislative Ideas» with the support of the Askold and Dir Fund as a part of the Strong Civil Society of Ukraine - a Driver towards Reforms and Democracy project, implemented by ISAR Ednannia, funded by Norway and Sweden. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Institute of Legislative Ideas and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Government of Norway, the Government of Sweden and ISAR Ednannia.

Summary

This analytical study examines the transposition of EU Directive 2024/1226 on the definition of criminal offences and penalties for violations of Union restrictive measures by EU Member States and the formulation of recommendations for improving Ukrainian sanctions legislation on the criminalisation of violations and circumvention of sanctions in connection with European integration.

A detailed comparative analysis was conducted of the experience of 16 EU Member States which, after the Directive entered into force, adopted special implementation acts or published relevant draft laws (Greece, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Germany, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, Finland, the Czech Republic, and Sweden). The study is structured in four sections and an appendix and covers the procedural aspects of transposition, forms and means of implementation, the scope of criminalisation of 12 types of violations and circumvention of restrictive measures, methods of formulating acts, cost thresholds for criminalisation, the system of penalties for individuals, aggravating and mitigating circumstances.

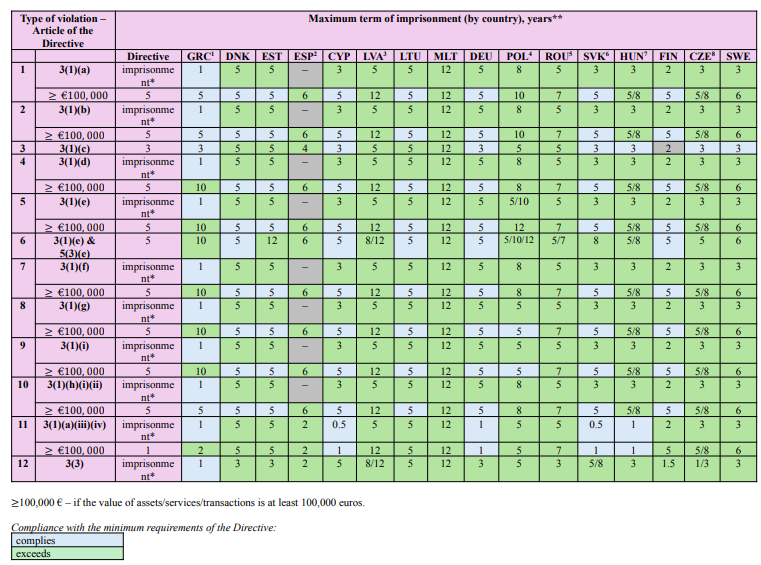

Two main approaches to the formulation of acts have been identified: abstract (general formulation of ‘sanctions violations’) and specific (detailed list of 8 forms of violations and 4 forms of circumvention of sanctions in accordance with Article 3 of the Directive). Most states have chosen to amend their criminal codes, mainly by placing the relevant provisions in sections on international crimes, crimes against the state or economic crimes. States are moving significantly away from the minimum requirements of the Directive on punishability towards tougher penalties, setting maximum prison terms of 5 to 12 years. Only some countries have introduced an optional value threshold for criminalisation of €10,000.

For Ukraine, it is recommended to systematically update the sanctions legislation, which provides for the revision of the Law ‘On Sanctions’, the establishment of a formal composition of the crime, the inclusion of criminal provisions in the Criminal Code as crimes against peace or the state, the introduction of a value threshold of around €10,000 with administrative liability for minor violations, mandatory criminalisation of negligent violations regarding military and dual-use goods, differentiation of liability depending on the severity of violations, and the creation of a coordinating body in the field of sanctions policy.

Introduction

Sanctions are one of the most important tools for countering actions that threaten a country's national security or even the international legal order. In the context of today's challenges to international security, the role of sanctions is growing significantly, prompting constant improvement of the mechanisms for their application.

In the European context, the issue of sanctions policy has become particularly relevant since Russia's brazen invasion of Ukraine in 2014. In response to these illegal actions, in March of that year, the Council of the European Union adopted Regulation No. 269/2014 of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine. This document introduced personal sanctions against Russian accomplices, in particular representatives of the occupying authorities of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

However, these measures were not the only manifestation of the European countries' position on Russia's illegal actions. In July 2014, Regulation No. 833/2014 of 31 July 2014 concerning restrictive measures in view of Russia's actions destabilising the situation in Ukraine was adopted, introducing sectoral sanctions against key areas of the Russian economy. However, these measures were limited in nature and did not exert systematic pressure on the Russian economy.

The situation changed after the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022. The scale of sanctions pressure on Russia has increased significantly. As of August 2025, the European Union alone has imposed 18 packages of sanctions, and, according to the head of the European Commission, a 19th package of sanctions is in preparation. However, sanctions pressure on Russia is not only being exerted by the EU. The United Kingdom is taking an equally active stance in this regard, systematically imposing sanctions on the aggressor state's accomplices.

Other countries in the sanctions coalition, including the United States, Switzerland and others, are also making significant contributions to the formation of sustained international sanctions pressure on Russia. As a result of the joint efforts of the international community against Russia, an unprecedented number of sanctions have been imposed – more than 23,000, making it the most sanctioned entity.

However, the application of sanctions against the aggressor and those who support it is only part of a systematic approach to achieving the goal of introducing this instrument. It is also extremely important to create effective tools to ensure compliance with sanctions and to bring violators to justice.

The experience of the European Union, which in recent years has been working particularly hard to improve the legal framework for sanctions policy, is significant in this context. In accordance with Article 83(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, the European Parliament and the Council may, by means of directives, regulate minimum rules concerning the definition of criminal offences and sanctions for their commission in the area of particularly serious cross-border crime.

By Decision No. 2022/2332 of 28 July 2022, the Council of the EU classified violations of restrictive measures as criminal activities that meet the criteria set out in Article 83(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Thus, the European Union has obtained a legal basis for establishing a minimum standard for regulating criminal liability for sanctions violations.

However, the differentiated approach of EU Member States to regulating the issue of liability for sanctions violations has led to significant differences in the definition and scope of the concept of sanctions violations, the types and severity of penalties for committed acts, as well as other compulsory measures applied to violators. This problem is also highlighted in recital 12 of EU Council Decision No. 2022/2332, which states: “The fact that Member States have very different definitions of and penalties for the violation of Union restrictive measures under their national laws contributes to different degrees of enforcement of sanctions, depending on the Member State where the infringement is pursued. This undermines the Union objectives of safeguarding international peace and security and upholding Union common values. Therefore, there is a particular need for common action at Union level to address the violation of Union restrictive measures by means of criminal law”.

That is why, on 24 April 2024, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU exercised their powers to set a minimum standard for regulating liability for sanctions violations by adopting Directive 2024/1226 on the definition of criminal offences and penalties for the violation of Union restrictive measures and amending Directive (EU) 2018/1673.

Directive (EU) 2024/1226 establishes a legal framework to ensure the effectiveness of the EU's sanctions policy and covers the following issues:

- a list of acts covered by the concept of "sanctions violations";

- forms of guilt;

- the optional criminalisation threshold;

- types of penalties applicable to natural and legal persons;

- circumstances that mitigate or aggravate penalties;

- statutes of limitations for violations committed;

- rules of jurisdiction;

- investigation tools, coordination and cooperation between the competent authorities of Member States and EU institutions;

- other criminal law measures.

Given the legal nature of the document, EU Member States are required to implement its provisions into national legislation. In this context, it is worth recalling that Article 83 TFEU only sets out ‘minimum rules’, so when implementing the provisions of the Directive, Member States may introduce stricter legislation, in particular by criminalising acts not covered by the Directive or by providing for more severe penalties for the commission of acts.

The deadline for implementing Directive (EU) 2024/1226 is 20 May 2025.

However, as of August 2025, the results of the implementation of Directive (EU) 2024/1226 show significant differences among Member States. Some EU Member States have fulfilled their obligations. These countries include Denmark, Estonia, Finland, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Latvia and Slovakia.

Denmark is a good example in this context. In accordance with Article 2 of Protocol No. 22 on the position of Denmark, annexed to the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Denmark was not obliged to implement the provisions of Directive (EU) 2024/1226. Nevertheless, on 20 June 2025, it adopted the relevant legislation.

At the same time, a significant number of EU Member States have not yet completed the implementation process. As a result, on 24 July 2025, the European Commission announced that it was initiating proceedings against 18 EU Member States (Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Hungary, Malta, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovenia) that had not notified measures to fully implement Directive (EU) 2024/1226 into national law. This calls for a detailed analysis of Member States' approaches to implementing the provisions of the Directive and identifying best practices for implementation.

The purpose of this analytical study is to examine best practices for implementing the provisions of Directive (EU) 2024/1226 into the national legislation of Member States, as well as to formulate conclusions and recommendations for improving Ukrainian sanctions legislation regarding the criminalisation of violations and circumvention of sanctions in connection with European integration.

In view of this, the scope of the study covers only those EU Member States which, after the entry into force of Directive (EU) 2024/1226, adopted legislation containing new criminal provisions for the purpose of transposing this Directive or officially published in open access drafts of relevant acts developed for the purpose of such transposition.

The subject of the study is limited to those provisions of adopted legislative acts or published draft laws that directly relate to:

- procedural aspects of transposition, the understanding of which is a necessary initial step towards the development and adoption of the necessary legislative changes by Ukraine (section 1 of the analysis);

- the criminalisation of violations of restrictive measures, including the methods, forms and means of its implementation, and the scope of criminalisation (section 2 of the analysis);

- penalisation – ensuring compliance with the provisions of the Directive in terms of determining the punishability of violations of restrictive measures (section 3 of the analysis);

Particular attention is paid to the formulation of general conclusions and recommendations for Ukraine (section 4 of the analysis).

1 Transposition – procedural aspects (Articles 19 and 20 of the EU Directive)

І) Тransposition of EU directives: legal basis

Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (excerpt)

Article 83.

- 1 The European Parliament and the Council may, by means of directives adopted in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, establish minimum rules concerning the definition of criminal offences and sanctions in the areas of particularly serious crime with a cross-border dimension resulting from the nature or impact of such offences or from a special need to combat them on a common basis.

These areas of crime are the following: terrorism, trafficking in human beings and sexual exploitation of women and children, illicit drug trafficking, illicit arms trafficking, money laundering, corruption, counterfeiting of means of payment, computer crime and organised crime.

On the basis of developments in crime, the Council may adopt a decision identifying other areas of crime that meet the criteria specified in this paragraph. It shall act unanimously after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

- 2 If the approximation of criminal laws and regulations of the Member States proves essential to ensure the effective implementation of a Union policy in an area which has been subject to harmonisation measures, directives may establish minimum rules with regard to the definition of criminal offences and sanctions in the area concerned. Such directives shall be adopted by the same ordinary or special legislative procedure as was followed for the adoption of the harmonisation measures in question, without prejudice to Article 76 (...)

Article 288.

To exercise the Union's competences, the institutions shall adopt regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions.

A regulation shall have general application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.

A directive shall be binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods.

A decision shall be binding in its entirety. A decision which specifies those to whom it is addressed shall be binding only on them.

Recommendations and opinions shall have no binding force.

Directives are a specific type of EU act which: a) is binding on Member States; b) is binding as to the result to be achieved; c) leaves Member States free to choose the form and means of achieving the result; d) is not, with certain exceptions, directly applicable in Member States; e) has different national effects .

The transposition of an EU directive can be seen as a process during which EU Member States implement (incorporate) the provisions of the directive into their national legislation, or as a result – the state of compliance of a Member State's national legislation (and subsequently its application) with the provisions of the directive.

EU directives set out the mandatory results that states must achieve, but they allow national authorities to choose the form and methods for achieving them. This ensures the consistency of member states' legislation with EU law.

Nota Bene! Article 83 TFEU provides only for a ‘minimum method of harmonisation’: Member States may maintain or introduce stricter legislation, i.e. criminalise conduct not covered by the directive, or provide for stricter penalties or other measures, but they cannot provide for a lesser degree of criminalisation or penalisation than that provided for in the relevant directive.

ІІ) transposition rules in EU Directive 2024/1226 (time limit)

EU Directive 2024/1226 (excerpt)

Article 20. Transposition

- 1 Member States shall bring into force the laws, regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with this Directive by 20 May 2025. They shall immediately inform the Commission thereof.

When Member States adopt those measures, they shall contain a reference to this Directive or shall be accompanied by such reference on the occasion of their official publication. The method of making such a reference shall be laid down by Member States.

- 2 Member States shall communicate to the Commission the text of the main measures of national law which they adopt in the field covered by this Directive.

EU Directive 2024/1226 sets 20 May 2025 as the deadline for transposition. However, this refers specifically to the entry into force of the necessary regulations, not their adoption. One year is actually quite a short period for a procedure that involves initiation, drafting, discussion and consultation, adoption, publication and entry into force. The short deadline clearly demonstrates the importance of the issue of the effectiveness of restrictive measures in the EU.

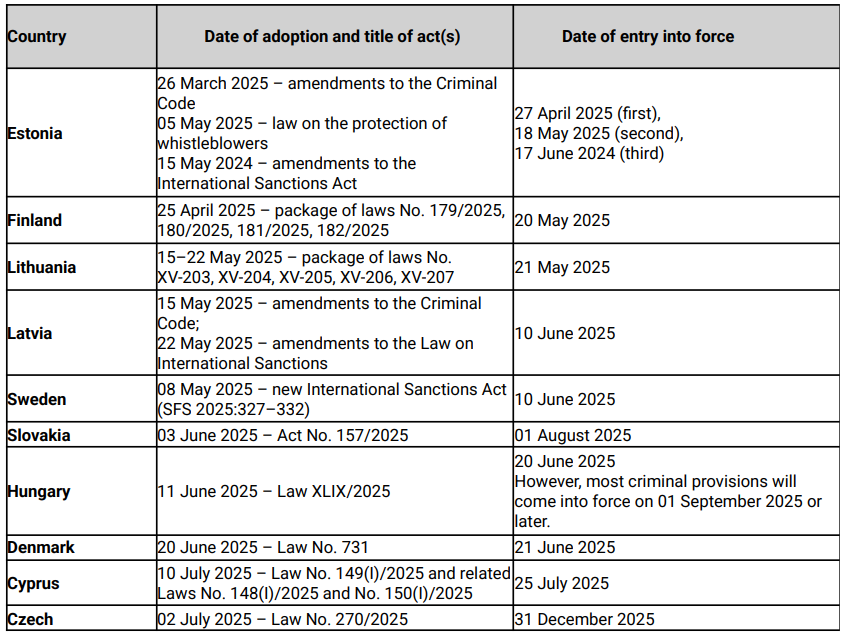

Among the Member States that did not have their legislation fully compliant with the requirements of EU Directive 2024/1226 at the time of its entry into force, only two countries, Estonia and Finland, complied with the requirements of Article 20(1) regarding the transposition deadline. Three other countries, Lithuania, Latvia and Sweden, ensured the adoption of implementing acts by 20 May 2025, but these came into force after the deadline had passed. Finally, five other countries – Slovakia, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Cyprus – adopted the relevant acts after the deadline. It is easy to see that the Baltic and Scandinavian countries have been the most active in this regard. It should also be noted that these same countries have been among the most active in terms of concentrating their efforts and implementing various measures to combat sanctions violations during the period 2022–2025.

Table 1: Dates of adoption and entry into force of acts transposing Directive (EU) 2024/1226 (among the group of countries that have adopted specific implementation acts):

Greece, Spain, Malta, Germany, Poland and Romania have prepared and published implementation drafts, which are currently under discussion. Public discussions and comments on them mostly indicate a positive decision on their adoption.

Italy, on the other hand, is currently significantly behind schedule with the transposition of the Directive. In June 2025, the Italian Parliament gave the Government 18 months to ensure transposition, which could mean that Italy is actually more than two years behind schedule.

ІІІ) forms and means of transposition

- Form of the implementing act

As follows from Article 288 TFEU, directives leave Member States free to choose the forms and methods/means of transposition. What matters is that they ensure proper legal force of the provisions, especially when it concerns the most severe restrictions of human rights provided for by criminal law, and their effectiveness. Obviously, in this context, it is for each state to decide on the form and content of the relevant implementing act, who should adopt it, and how many such acts should be adopted.

Member States have mostly adopted or requisite acts in the form of laws. This is natural, since the criminalisation of violations of EU restrictive measures results in the most serious restrictions on human rights characteristic of criminal law. Therefore, their adoption is, as a rule, the responsibility of parliaments – legislative bodies. The role of governments is limited to initiating, developing drafts and submitting them to parliaments.

At the same time, certain features related to the delegation of powers to executive bodies can be observed in some countries. Thus, in Romania, the criminal law enforcement of sanctions is based primarily on Government Emergency Ordinance No. 202/2008 on the implementation of international sanctions, the adoption of which was the result of the implementation of legislative powers delegated by parliament to the government, as well as on the Criminal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure and Law 302/2004 on international cooperation in criminal matters. The new draft law prepared by the government provides for amendments to the aforementioned Government Emergency Ordinance by parliament.

A similar original method of transposition is also used in Italy. In order to harmonise its legislation with the EU acquis, the Italian Parliament annually adopts the so-called ‘European delegation laws’ – an annual legislative instrument through which Parliament delegates to the Government the power to transpose EU directives and implement other EU legislative acts in order to overcome existing delays and prevent new ones in the integration of EU legislation. It would seem that delegating legislative powers to the Government should be an effective and rapid means of transposition, but actual practice in Italy shows a different experience: on 13 June 2025, the Italian Parliament adopted Law 2280/2025 on European delegation 2024, Art. 5 of which contains guidelines and principles for delegating powers to the government for the detailed transposition of EU Directive 2024/1226, but Article 2 gives the government 18 months to implement these guidelines.

- Criminal Code vs. Special Law

The transposition of EU Directive 2024/1226 shows a clear trend: the dominant approach is to amend criminal codes, while the adoption of separate special laws is, if not an exception, then a much less common way of criminalising and penalising violations of EU restrictive measures. Most countries (in particular, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Spain, and Finland) have chosen to amend their criminal codes (CC) as the main instrument of implementation, although some of them allow for the adoption of laws that establish criminal liability outside the Criminal Code.

While in Lithuania, Latvia and Denmark the provisions of the codes have undergone only minor changes to the wording of existing articles on sanctions violations, the criminal codes of other Member States have undergone significant changes and additions, or such changes are planned in the relevant drafts. This clearly demonstrates that the adoption of EU Directive 2024/1226 has necessitated extensive amendments to the criminal codes of many countries – regulatory acts that are generally revised relatively rarely and tend to be conservative. Thus, five new articles were added to the Slovak code, four new articles were added to the Hungarian code, three new articles were added to the Finnish code and five more underwent significant changes, two new articles were added to the Estonian code and one was revised, two new articles were added to the Czech code and several others were revised. The draft amendments to the Spanish Criminal Code provide for the addition of a new section containing eight articles.

It is interesting to note that articles providing for liability for violations of EU restrictive measures are placed (proposed to be placed) in sections aimed at protecting different interests (values), as evidenced by the titles of the relevant sections of the special parts of the criminal codes and “neighboring” criminal offenses. Violations of restrictive measures are classified as:

- economic crimes – Finland (Section 46 "Crimes related to import and export");

- international crimes – Slovakia (Section 12(I) "Crimes against peace and humanity, crimes of terrorism and extremism"), Estonia (Section 3 "Crimes against peace"), Czech Republic (Section XIII(II) "Crimes against peace and war crimes");

- crimes against the state – Latvia (Section X "Crimes against the State"), Lithuania (Section XIV "Crimes against the Independence, Territorial Integrity and Constitutional Order of the Lithuanian State"),

- crimes against the EU – Spain (Section XXIII-bis "Crimes against the area of freedom, security and justice of the European Union"),

- crimes against public safety – Hungary (Section XXXI “Crimes against economic regulation based on international obligations for the purposes of public safety”).

Other countries have defined criminal offences or plan to define them in special laws, although each of these countries has a codified act – the Criminal Code. However, the methods of transposition in these cases may vary significantly and depend on the characteristics of national legal systems and which specific path the legislator found more appropriate. At least three types of transposition within special laws can be distinguished:

First: transposition is ensured by means of laws specifically dedicated to the issues regulated by the Directive. Three countries have adopted or are planning to adopt laws that could be called "national copies" of EU Directive 2024/1226, as they almost completely reproduce its content, structure and wording (linguistic constructions).

- Cyprus has adopted the "Law on the Definition of Criminal Offences and Sanctions for Violations of Union Restrictive Measures," which contains 15 articles devoted to the criminalisation of violations of restrictive measures;

- Greece plans to adopt a law establishing offences and penalties against natural and legal persons for violations of EU restrictive measures, transposing Directive (EU) 2024/1226 of 24 April 2024. The law contains 21 articles, 15 of which are specifically devoted to the criminalisation of violations and circumvention of sanctions.

Both cases are excellent examples demonstrating these countries' commitment to ensuring the most complete and accurate transposition possible. These acts provide definitions of terms in strict accordance with Article 2 of the Directive, define acts that constitute violations and circumvention of sanctions in the same way as the Directive, and establish penalties for natural and legal persons, other criminal measures, investigation measures, rules for cooperation between competent authorities, protection of whistleblowers and even the process of collecting and submitting statistical data.

The close reproduction of the provisions of the EU Directive, moreover within a single law, undoubtedly contributes not only to the fulfilment of obligations under EU law, but also minimises the risk of differing interpretations of the newly adopted provisions. At the same time, an approach that involves "copying" the directive can only be implemented in national legal systems whose terminology is fully consistent with the terminology of the directive, since otherwise legal certainty may be compromised.

Second: transposition is ensured within the framework of new or updated comprehensive "sanctions laws" – i.e. laws dedicated to regulating both the application (enforcement) and administration of sanctions, as well as liability for violations of restrictive measures:

- In Malta, there are plans to adopt a new "Law on the Power to Adopt Regulatory Acts in the National Interest". Although the main purpose and reasons for this bill are to transpose EU Directive 2024/1226 into national law, it also updates the national system for regulating restrictive measures to ensure their compliance with current EU legislation (primarily regulations). The comprehensive approach consists in proposing to define in a single law not only various aspects of the criminalisation of violations and circumvention of sanctions, but also the rules for the application of restrictive measures, the content of restrictive measures, the powers of competent authorities, the obligations of sanctioned entities, banks and other financial institutions, the basis for cooperation between different authorities, etc.

- In Poland, the draft Law on Restrictive Measures proposes to create a so-called "sanctions constitution". It will be comprehensive in nature, as it will provide, among other things, for: the distribution of competences between various national authorities implementing restrictive measures and the creation of an inter-agency group for better coordination of their actions, the creation of a transparent system for the application of national restrictive measures, the implementation of Directive (EU) 2024/1226 into national law; systematisation of the implementation of EU, UN and national sanctions in the Republic of Poland (unified approach), as their application and enforcement has so far been regulated in part by different legal acts, which has hindered the effective implementation of sanctions and complicated their proper application by the entities subject to them.

- In Romania, a draft amendment to the provisions of Government Emergency Ordinance No. 202/2008 on the implementation of international sanctions has been developed and is under discussion. The proposed draft can also be considered an example of a comprehensive approach to the implementation of the provisions of the directive, as it provides for the transfer of most of the provisions of the directive into a single legislative act. An important advantage of this draft is that the same act will contain both the main provisions on the implementation of sanctions, their administration, and liability (administrative and criminal) for violations of these sanctions.

A special case is the new Swedish Law on International Sanctions. When transposing the EU Directive, the Swedish government decided to adopt a new law on sanctions altogether. In its explanations to the draft law, the government noted that the current Law on Sanctions appears difficult to understand in some parts. Several provisions also need to be revised, in particular as a result of the adoption of the Directive. In order to make the regulation more understandable and transparent, it was decided to implement the Directive in a new International Sanctions Act, which is to apply to all international sanctions. It contains provisions of criminal law and criminal procedure regarding violations of international sanctions, as well as specific provisions on how international sanctions that are not directly applicable should be implemented in Swedish law. The main criminal law provisions of EU Directive 2024/1226, set out in Articles 3 to 5 of the Directive, are transposed into national law as closely as possible to the relevant wording of the Directive. However, other provisions (Article 6 of the Directive and beyond) are reflected in the law to a lesser extent, as their effect is mainly ensured by the current Criminal Code and other acts.

As can be seen, the transposition of the EU Directive within the framework of specific comprehensive laws demonstrates not only the achievement of the goal of unifying approaches to liability for violations and circumvention of sanctions throughout the EU, but also that the EU Directive has provided an impetus for bringing order to the national sanctions legislation of individual Member States.

Third: in some cases, transposition is achieved by amending special regulatory laws in the relevant areas, due to the absence of specific laws on sanctions as such. For example, in Germany, the draft bill provides for amendments to specific laws governing foreign trade, customs and residence (stay) in Germany, respectively.

- Comparison of other transposition methods

Adopting a single legislative act or a package of laws is a decision left to the discretion of Member States, each of which has its own rules and traditions of law-making. To ensure the transposition of EU Directive 2024/1226, most Member States resort to adopting several separate laws that provide for amendments.

- For example, Lithuania prepared a package of draft amendments to various laws, including separate laws amending: the Criminal Code of the Republic of Lithuania and its annex (Law No. XV-204); the annex to the Code of Administrative Offences of the Republic of Lithuania (Law No. XV-205); the Law on International Sanctions (Law No. XV-203); the Law on Criminal Intelligence (Law No. XV-206); the Law on the Protection of Informants (Law No. XV-207).

- In Latvia, at least three draft laws were adopted, providing for amendments to: the Criminal Code of the Republic of Latvia (Law of 15 May 2025); the Law on the Entry into Force and Application of Criminal Law (Law of 15 May 2025); the Law of the Republic of Latvia on International and National Sanctions (Law of 22 May 2025). Overall, Latvia's regulatory framework largely complied with the requirements set out in the Directive. However, during transposition, it was concluded that amendments to the Criminal Code were necessary to define the scope of sanctions violations, the obligation to report possible criminal offences and mechanisms for cooperation in the field of sanctions enforcement .

- Estonia has adopted at least three legislative acts that ensure the transposition of the Directive: the Act Amending the Criminal Code and Related Amendments to Other Acts (Act of 26 March 2025); Law on Amendments to the Law on the Protection of Whistleblowers and the Law on International Sanctions (Law of 5 May 2025); Law on Amendments to the Law on International Sanctions and Other Related Laws (Law of 15 May 2024).

- In Finland, in order to fulfil its obligation to implement the provisions of the EU Directive, a package of laws was adopted on 25 April 2025: Law amending the Criminal Code (Law 179/2025); Act amending the Act on Enforcement Measures (Act 180/2025); Act amending the Act on the Protection of Persons Reporting Violations of EU and National Legislation (Act 181/2025); Act amending the Act on the Implementation of Certain Obligations of Finland as a Member of the UN and the EU (Act 182/2025).

In some countries, the legislative solution is to adopt a single act that amends several related laws. For example, Hungary adopted the Act Amending Judicial Legislation (Act XLIX 2025), which amends not only the Criminal Code but also other legislative acts and addresses more than just the transposition of the Directive. In Slovakia, Law 157/2025 was adopted, introducing amendments and additions, in particular, to the Criminal Code, the Law on the Protection of Whistleblowers and the Law on Criminal Liability of Legal Persons. In the Czech Republic, Act No. 270/2025 of 02.07.2025 amended the Criminal Code, the Criminal Procedure Code, the Act on International Judicial Cooperation in Criminal Matters, the Law on Criminal Liability of Legal Entities and other laws (only part of which concerns the transposition of EU Directive 2024/1226).

In August 2025, the German government presented a draft law on the adaptation of criminal offences and sanctions for violations of EU restrictive measures, which serves to implement the EU directive and amends several laws at the same time, in particular: the Foreign Trade and Payments Act (AWG), the Foreign Trade Ordinance (AWV), the Residence Act (AufenthG) and the Customs Investigation Service Act (ZFdG).

The need to adopt a package of laws or to amend various laws in a single act is due to the fact that the provisions of EU Directive 2024/1226 do not only concern criminal law. They also create obligations for Member States in the areas of investigation procedures (criminal proceedings), procedures for reporting offences and protecting whistleblowers, etc. In addition, the criminalisation of certain violations and circumvention of sanctions requires prior amendment of the legislation on the application of sanctions, in particular with regard to the obligation to report and notify, harmonisation of terminology, etc.

At the same time, a number of Member States, primarily those that are adopting or updating comprehensive special laws, have adopted or plan to adopt a single act (law) that reproduces the provisions of EU Directive 2024/1226 as closely as possible (in particular, Greece, Malta, Poland, Romania).

IV) reference to EU Directive 2024/1226

When adopting the relevant regulations, Member States ensured that a reference to the Directive was included and/or accompanied their official publication with such a reference.

As a rule, a direct reference was provided in national legislation: a reference to EU Directive 2024/1226 is provided in the text of the adopted national law. This reference is usually contained in the preamble, the explanatory (introductory) part of the regulatory act, which explains the purpose of the law, especially when it comes to laws amending other acts. In other cases, a separate article of the law, its final provisions or special annexes contain a list of EU acts (directives, regulations, decisions) whose provisions are implemented in such a law.

For example, paragraph 2 of the preamble to Hungarian Law XLIX of 2025 on amendments states that "the amendments to the legislation ensure the fulfilment of Hungary's international and legal obligations to the EU, in particular the implementation of Directive (EU) 2024/1226, which provides for the criminalisation of violations of international economic sanctions." In turn, Section 465 of the Criminal Code ("Compliance with European Union legislation"), as well as a number of other laws, includes a reference to the Directive, confirming its implementation into the relevant act. The transposition of the Directive is mentioned in Article 1 of the Maltese draft law, which describes the purpose of the law. In the new Swedish Law on International Sanctions, the reference to the implementation of EU Directive 2024/1226 is contained in Article (§) 1 of the law.

Another example is Slovak Law 157/2025, which ensures transposition by amending the Criminal Code and two other laws by adding a reference to the Directive in the annexes to these laws. These annexes contain a list of all EU acts transposed into the relevant act. The same reference in a separate article of the annex to the Criminal Code is also provided for in the relevant Lithuanian law on amendments.

In some cases, the reference to EU Directive 2024/1226 is already included in the title of the relevant act. For example, the full title of the Greek draft law is "Establishment of criminal offences and sanctions against natural and legal persons for violations of European Union restrictive measures, implementation of Directive (EU) 2024/1226 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the definition of criminal offences and penalties for the violation of Union restrictive measures and amending Directive (EU) 2018/1673 and other provisions."

Accompanying documents (e.g. explanatory notes, impact assessments or official reports) often contain explicit references to EU Directive 2024/1226, explaining how the national law complies with or transposes the provisions of this Directive. Member States also create and often publish a special transposition table or overview document accompanying the national legislation. This document compares the provisions of the EU Directive with those of national legislation, showing how each point of the Directive has been transposed into national law. For example, good examples of comparative tables can be found in Lithuania ("Table of correlation between Directive (EU) 2024/1226 and national legislation and draft legislation"), Poland ("Table of alignment with the Directive"), the Czech Republic ("Tables of compliance with EU legislation").

Another example is the Minister of Justice and Security of the Netherlands, who announced through an official publication that Directive (EU) 2024/1226 had been implemented through the introduction of existing regulations, adding a transposition table as confirmation.

V) assessment of the degree of implementation of the Directive

As noted above, two months after the transposition deadline (and 14 months after the Directive entered into force), the European Commission initiated proceedings against 18 of the 27 EU Member States as they had not notified the Commission of measures to fully implement Directive (EU) 2024/1226 into national law. Some of the states that missed the deadline have already adopted legislative acts for transposition, and some of them managed to do so even before the European Commission's announcement (e.g., Cyprus, the Czech Republic, and Hungary). At the same time, these facts do not yet mean that these countries have fulfilled their obligations, as each of them has so far only conducted an internal (national) assessment of the implementation of the directive.

According to Article 19(1) of EU Directive 2024/1226, by 20 May 2027, the European Commission must submit a report to the European Parliament and to the Council, assessing the extent to which the Member States have taken the necessary measures to comply with this Directive. Therefore, the final assessment of whether each Member State has fully implemented the provisions of the Directive into its legislation will take place a little later, based on an external analysis by the Commission and the actual practice of applying the newly adopted provisions.

2 Criminalising violations of Union restrictive measures (Articles 3 and 4 of the EU Directive)

І) general content and meaning of Article 3 of the EU Directive

Paragraph 1 of Article 3 contains provisions that can be considered a "mini-directive" within the Directive. These provisions are central and play a systemic role for the other provisions of the Directive.

EU Directive 2024/1226 (excerpt)

Article 3.

Violation of Union restrictive measures

- Member States shall ensure that, where it is intentional and in violation of a prohibition or an obligation that constitutes a Union restrictive measure or that is set out in a national provision implementing a Union restrictive measure, where national implementation is required, the following conduct constitutes a criminal offence:

- (a) making funds or economic resources available directly or indirectly to, or for the benefit of, a designated person, entity or body in violation of a prohibition that constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (b) failing to freeze funds or economic resources belonging to or owned, held or controlled by a designated person, entity or body in violation of an obligation that constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (c) enabling designated natural persons to enter into, or transit through, the territory of a Member State, in violation of a prohibition that constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (d) entering into or continuing transactions with a third State, bodies of a third State or entities or bodies directly or indirectly owned or controlled by a third State or by bodies of a third State, including the award or continued execution of public or concession contracts, where the prohibition or restriction of that conduct constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (e) trading, importing, exporting, selling, purchasing, transferring, transiting or transporting goods, as well as providing brokering services, technical assistance or other services relating to those goods, where the prohibition or restriction of that conduct constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (f) providing financial services or performing financial activities, where the prohibition or restriction of that conduct constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (g) providing services other than those referred to in point (f), where the prohibition or restriction of that conduct constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

- (h) circumventing a Union restrictive measure by:

- using, transferring to a third party, or otherwise disposing of, funds or economic resources directly or indirectly owned, held, or controlled by a designated person, entity or body, which are to be frozen pursuant to a Union restrictive measure, in order to conceal those funds or economic resources;

- providing false or misleading information to conceal the fact that a designated person, entity or body is the ultimate owner or beneficiary of funds or economic resources which are to be frozen pursuant to a Union restrictive measure;

- failing by a designated natural person, or by a representative of a designated entity or body, to comply with an obligation that constitutes a Union restrictive measure to report to the competent administrative authorities funds or economic resources within the jurisdiction of a Member State, belonging to, owned, held, or controlled by them;

- failing to comply with an obligation that constitutes a Union restrictive measures to provide the competent administrative authorities with information on frozen funds or economic resources or information held about funds or economic resources within the territory of the Member States, belonging to, owned, held or controlled by designated persons, entities or bodies and which have not been frozen, where such information was obtained in the performance of a professional duty;

- (i) breaching or failing to fulfil conditions under authorisations granted by competent authorities to conduct activities, which in the absence of such an authorisation amount to a violation of a prohibition or restriction that constitutes a Union restrictive measure;

In view of the content of Article 3(1), the following conclusions can be drawn about the provisions of the Directive on the criminalisation of violations of Union restrictive measures:

- Article 3(1) generally contains nine specific types (forms) of acts that are recognised as restrictive measures (points (a) to (i)), which are characterised by a common feature – these acts are not punishable per se, but only if they violate prohibitions, restrictions or obligations that: (a) constitute a Union restrictive measure, or (b) are established by national provisions implementing a Union restrictive measure;

- among these nine types of acts, circumvention of a restrictive measure (point (h)) is clearly distinguished, which in turn is divided into four subtypes:

transactions involving frozen assets (point (h)(i)),

misrepresentation of the real owner of the assets (point (h)(ii)), and

breach of the obligation to report assets by a designated person (point (h)(iii)) or

reporting of assets by a professional entity (point (h)(iv)).

As a result, one can distinguish 8 forms of sanctions violations (clauses (a) – (g) and (i)) and 4 forms of circumvention (clauses (h)(i) – (iv));

- violations of restrictive measures provided for in paragraphs 3(1)(a) – (d) are formulated in such a way that they criminalise violations not so much by a designated person (sanctioned entity) but rather by other entities – professionals (in particular, employees of financial institutions) and third parties: providing assets to a designated person, facilitating their entry or transit, not freezing their assets, and entering into agreements with a sanctioned state. However, in reality, due to the provisions on complicity, designated persons also fall under these rules;

- violations of restrictive measures provided for in paragraph 3(1)(e) – (g), (i) literally apply to any entities (designated persons, professionals, third parties): carrying out various trade operations with goods, providing services or carrying out financial activities that are prohibited or restricted by sanctions, as well as performing actions in violation of the terms of the authorisation. In these cases, the provisions on complicity are also applicable;

- given the "minimum rules" standard in the Directive, the focus is on intentional violations of sanctions, although there is a noticeable positive attitude towards prosecution for negligent violations (see below).

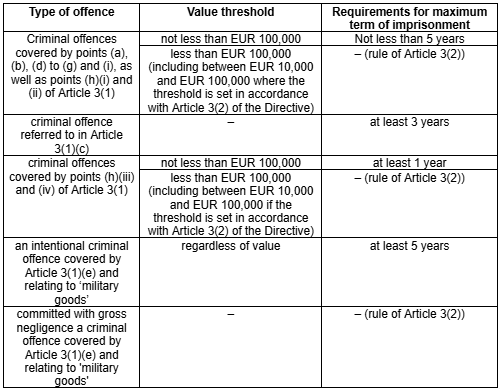

Ensuring the implementation of the principle of proportionality, EU Directive 2024/1226 provides that not all violations of EU restrictive measures must necessarily be subject to criminal liability. Violations for which there is no requirement for criminalisation are:

- intentional violations of EU restrictive measures that fall under the value exception (up to €10,000) provided for in Article 3(2), with the exception of "military goods";

- intentional violations of EU restrictive measures not covered by Article 3(1);

- negligent violations of EU restrictive measures, except for the mandatory exemption for "military goods" provided for in Article 3(2).

Member States have discretion regarding these acts: they may choose not to consider them criminal offences and provide for administrative (civil) measures or no liability at all, or they may ultimately define them as criminal offences.

II) Scope of criminalisation

One of the most important consequences of the adoption of EU Directive 2024/1226 is to ensure criminal liability for violations and circumvention of sanctions throughout the Union. The goal of ensuring a uniform approach to defining criminal offences and penalties for them cannot be achieved if several Member States do not have a specific provision providing for criminal penalties specifically for violations and circumvention of sanctions. In this sense, because of the Directive, three countries have begun the process of criminalising the respective actions for the first time (criminalisation "from scratch"):

- Thus, the Criminal Code of Slovakia, Law 157/2025 on amendments and additions to the Criminal Code and on amendments and additions to certain laws, in addition to minor changes to existing articles, was also supplemented with six new articles. The significance of the changes resulting from the implementation of the provisions of the Directive was primarily due to the fact that previously, only administrative liability for violations of sanctions existed in Slovakia.

- Spain is also one of the countries where violation or circumvention of an EU restrictive measure is not a separate (independent) criminal offence. Therefore, on 25 March, the Spanish Council of Ministers approved the preliminary draft of the Organic Law amending the Criminal Code to transpose Directive 2024/1226 EU, which proposes significant changes to the Spanish Criminal Code: in addition to the amendments to Article 301, the Criminal Code is supplemented by a new Section XXIII-bis, which contains as many as 8 new articles.

- After analysing the provisions of EU Directive 2024/1226 in relation to the national legal framework in Romania, it became clear that a new draft legislative act was needed to ensure the transposition of the Directive: the violation of international sanctions in Romania does not have a clearly defined separate offence in the Criminal Code, but may be covered by a number of articles on other general offences depending on the nature of the act (influence peddling, abuse of power, etc.). The draft amendment to Government Emergency Ordinance No. 202/2008 on the implementation of international sanctions provides for the implementation of the provisions of the Directive by supplementing the Emergency Ordinance with Section V on (administrative) offences, which is proposed to be linked entirely to the condition of "no evidence of a crime", with a separate section V-1 "Crimes", which provides for 7 new articles.

This means that these states have implemented (or plan to implement) the most comprehensive criminalisation of acts in the sense that all acts defined in Article 3(1) of the Directive are transformed from non-punishable (or only administratively punishable) to criminal, with the exception of certain acts covered by classic general criminal provisions.

Other EU Member States already had specific criminal provisions criminalising violations of restrictive measures at the time EU Directive 2024/1226 entered into force. In view of this, the scope of criminalisation in such states varies depending on the extent to which their existing provisions already covered the acts referred to in Article 3(1). Thus, in the context of the transposition of Article 3(1) of the Directive (i.e. in terms of criminalisation), Article 110c of the Danish Criminal Code was amended with regard to "military goods", while Article 123-1 of the Lithuanian Criminal Code was amended only with regard to negligent violations of sanctions and violations in the form of facilitating the entry or transit of a designated person through Lithuanian territory. A broader scope of criminalisation can be seen, in particular, in the draft legislative changes developed in Germany and Poland.

Some Member States have declared full compliance with regard to the criminalisation of sanctions violations. For example, in its public communication on Article 3(1) (as well as on other articles of the Directive), the Netherlands noted that violations of the prohibitions and obligations set out in Union acts on the application of sanctions are already punishable, even more broadly (more severely) than required by the Directive. It is possible that a number of other states against which the Commission has initiated proceedings for failure to notify transposition measures already have an adequate level of criminalisation and other compliance with the Directive.

III) conflicts of criminal provisions

Criminalization often leads to conflict between different provisions of criminal law. As a result, the same behavior may be treated under various articles of criminal law, leading to inconsistent application of the law in similar circumstances or to unjustified treatment under the rule on cumulative offenses.

This problem is exacerbated in cases of ‘criminalisation from scratch’. In Spain, the current regulatory framework provides for fragmented coverage of sanctions for different violations of restrictive measures: violations of certain EU measures fall under more general criminal or civil (administrative) offences, such as smuggling or money laundering . In Romania, Article 26 of the current Emergency Ordinance No. 202/2008 provides for a fine for violations of certain provisions of the ordinance, provided that such an act is not a crime. At the same time, in the Criminal Code, violation of international sanctions does not constitute a separate offence, but may be covered by a number of articles on other general offences, depending on the nature of the act: abuse of office (if an official facilitates the circumvention of sanctions or fails to fulfil their duties regarding their implementation), trading in influence (when sanctions are circumvented through corruption schemes or the use of personal connections), document forgery, violation of export control regime, fraud or money laundering.

The draft laws in Spain and Romania that plan to adopt rules on criminal violations of sanctions provide for the creation of special rules. In this case, they may compete with more general rules. The draft laws do not contain any special provisions that could resolve this issue, which means that traditional principles developed by criminal law doctrine will apply. The general rule for resolving conflicts is well known – lex specialis derogat legi generali (a special law takes precedence over a general law) – but this does not exclude the rule on multiple offences. In this regard, the explanatory memorandum to the Spanish draft law recognises the possibility of conflicts or classification under the rule of ideal concurrence as a result of the transposition of the EU Directive, since general criminal provisions on smuggling, disobedience or money laundering still remain applicable. However, it is assumed that special provisions will apply.

The Finnish Criminal Code, which covers the entire spectrum of crimes, contained a very general provision prior to transposition: Section 46 on crimes related to import and export contained the universal crime of "Violation of established rules" (§ 1), paragraphs 1 and 9 of which provided that anyone who violates or attempts to violate, in particular, legislation on the fulfilment of certain obligations of Finland as a member of the UN and the EU, or legislation in the field of the EU's common foreign and security policy on the basis of Article 215 TFEU on the termination of economic/financial relations with a third country or on the application of restrictive measures provided for in regulations or on the basis of the aforementioned normative acts, shall be punished by a fine or imprisonment for up to two years. The new Act added four new articles to this section with special provisions on "Violation of sanctions" (§ 3a), "Aggravated violation of sanctions" (§ 3b), "Negligent violation of sanctions" (§ 3c) and "Minor violation of sanctions" (§ 3d). To avoid conflict between general and special provisions, the "general" paragraphs 1 and 9 were deleted. In addition, a conflict provision was added to § 4 ("Smuggling") stating that a violation of the provisions or regulations on import or export specified in §§3a–3d is not considered smuggling.

In Greece, liability for violations of EU restrictive measures is currently provided for in Article 142-A of the Criminal Code (Law 4619/2019) and the Law on the Prevention and Suppression of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Law 4557/2018). The Greek Criminal Code already contains a rule to overcome potential conflicts, as it provides for imprisonment of up to two years for intentional violation of restrictive measures, provided that no other provision provides for a more severe penalty. Therefore, if the government's draft law on the transposition of the Directive is adopted, the new provisions of the law will be specific to Article 142-A of the Criminal Code.

Poland, in turn, has also only partially ensured the compliance of its legislation with EU Directive 2024/1226 through the existing provisions of the Criminal Code and Article 15 of the Act on Specific Measures to Counter Support for Aggression against Ukraine and to Protect National Security, which provide for criminal offences for violations of EU regulations on restrictive measures against Russia, Belarus and the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (Law of 13 April 2022). The provisions of this Law have a narrower scope than those of the Directive, which covers not only violations of restrictive measures imposed in connection with the war in Ukraine, but also all EU legal acts on restrictive measures. The explanatory notes to the draft law state that the "special law" adopted in connection with Russian aggression against Ukraine will remain in force in view of the exceptional international situation, the specific nature of the current regulation and the number of cases being considered under it. However, its criminal provisions (Article 15) are proposed to be amended or repealed in order to bring them into line with the new general law. Due to the fact that the "special law" will not be repealed in its entirety, the new draft law has been criticised, as the harmonisation will only be partial – the provisions on sanctions will continue to be scattered.

IV) corpus delicti

Article 3(1) does not refer to the causing of property damage or other harm by acts defined as violations or circumvention of restrictive measures. In other words, the corpus delicti of the criminal offence proposed by EU Directive 2024/1226 is a conduct crime (or so-called "victimless crime"). In other words, the Directive requires Member States to recognise a person's conduct as a violation of a restrictive measure based solely on the act itself, even if it did not cause any specific property damage or other harm.

An analysis of the transposition shows that the conduct crime approach prevails among Member States: most states recognise the violation or circumvention of sanctions as punishable, regardless of the actual consequences.

However, Article 123-1 of the Criminal Code of Lithuania defines a criminal offence as a violation of international sanctions in force or established in the Republic of Lithuania that has caused significant damage. This "general" type of violation of sanctions therefore is a result crime, i.e. it requires the occurrence of a consequence in the form of significant damage.

In the comparative table to the draft law, the Lithuanian government's arguments regarding the result-crime approach are based on the desire to avoid unjustified expansion of the criminalisation of unlawful conduct. According to the government, the criterion of "significant damage" is evaluative and will be of a mixed nature, as it can be both property-related (direct losses, expenses, lost profits) and non-property-related (physical, moral, organisational and other types of damage), which was previously interpreted by the Supreme Court of Lithuania in a comparative aspect in a case concerning abuse of power (Article 228 of the Criminal Code). The evaluative nature of the criterion means that the amount of damage will be assessed taking into account the circumstances of the specific case: the nature of the committed actions, the interests violated, the number of victims, the duration of the criminal act, the importance of the person's current situation, the resonance in society, the authority of the state, etc. In its explanations, the government notes that even a significant amount in the context of a violation of restrictive measures would be interpreted in financial terms as a sum of money exceeding €10,000, although at the same time it would be possible to bring persons to criminal responsibility for violating international sanctions when the amount does not reach €10,000 but significant damage has been caused to state interests (non-material damage).

Certainly, Article 3(2) of EU Directive 2024/1226 allows Member States to set a value threshold for funds, economic resources, goods, transactions and services in respect of which the acts specified in Article 3(1) are committed. However, their value is not equivalent to the damage caused: committing acts even in relation to assets or services worth more than €10,000 does not necessarily cause property damage at all or property damage of the same value. One thing is certain: the Directive requires the criminalisation of violations and circumvention of sanctions regardless of any damage. Moreover, even among the list of aggravating circumstances provided for in Article 8 of the Directive, there are none relating to the amount of damage. Thus, it is unlikely that Lithuania's approach, based on the mandatory proof of significant damage from the violation, meets the requirements of Article 3 of the Directive.

V) ways of describing the actus reus (specification of ways of violating sanctions)

Prior to the adoption of EU Directive 2024/1226, the criminal laws of EU Member States provided for a predominantly general (abstract) formulation of the act: "violation of restrictive measures/prohibitions, restrictions, obligations...", "anyone who has violated an international sanction...". The transposition of the Directive initiated the opposite trend – many Member States took the path of specification, outlining several forms of violations of restrictive measures. The source of the trend towards specifying the forms (types) of behaviour that constitute violations of sanctions is Article 3(1), which contains an exhaustive list of acts.

In general, two main ways of formulating actus reus can be distinguished when Member States define types of violations of Union restrictive measures:

the first is an abstract (unspecified, vaguely specified) method: it involves the most generalised (unspecified) formulation of an act, which in terms of content only indicates its unlawful nature, but does not allow the actual content of the act to be ascertained. Along with such an act, certain specific types of violations may also be envisaged, but in general the content of the act remains rather general than specific:

- Estonia: the previous version of Article 93-1 of the Criminal Code, “Violation of international sanctions and sanctions of the Government of the Republic”, provided for the most general wording to describe an unlawful act – “failure to comply with an obligation or violation of a prohibition”. With the adoption of the transposition law, unlawful behaviour has not been defined more specifically. The added Article 93-2 also contains the most general wording possible, but for negligent violation of sanctions – “failure to comply with an obligation or violation of a prohibition established in a legal act that applies international sanctions or establishes sanctions of the Government of the Republic through negligence”.

- Denmark: in §110-c of the Danish Criminal Code, the act remains broadly defined even after transposition, without any specification, as a violation of Council measures contained in or issued pursuant to regulatory acts and which are aimed at interrupting or restricting, in whole or in part, financial or economic relations with one or more countries, or at imposing restrictive measures on individuals, groups of individuals or legal entities. At the same time, separate paragraphs defined violations of legislation on weapons and explosives, if the violation concerns restrictive measures, as well as trade, import, export, sale, purchase, transfer, transit or movement of military and dual-use goods (hereinafter referred to as "military goods"). However, the penalties for these specific types of violations are identical to those for general violations, which calls into question the rationale for establishing specific rules.

- Latvia: prior to the amendments, there was no specification of the act, and in general, the actions of a person violating the sanction were punishable, i.e. the act was formulated in the most generalised way possible. After transposition, only partial specification took place. As a result, the current version of Article 84(1) of the Latvian Criminal Code provides for one specific type of violation of sanctions – through the purchase, sale, moving goods subject to sanctions across the state border, providing intermediary services, technical assistance or other services related to goods, or performing any other prohibited actions with these goods, if this was done on a significant scale (special type), and one general type – other violations of sanctions. Paragraph 2 of Article 84 contains another special type of violation, which concerns military and dual-use goods.

Czech Republic: even before the law implementing the Directive came into force, the Czech Criminal Code already contained a special article – § 410 on violations of international sanctions. Taking into account the amending law, the Czech Criminal Code also provides for a general, unspecified provision on violations of international sanctions in §410 (1). At the same time, two special types are now distinguished: violations by allowing a sanctioned person to enter or transit through the Czech Republic (§410(2)), and violations relating to "military goods" committed with gross negligence, regardless of the value of the goods (§410a).

The list of countries that use the general term “violation” is likely to be much longer, taking into account other EU Member States, which are not analysed in this study because they did not adopt specific criminal provisions after the Directive came into force.

The main advantage of an abstract (unspecified) approach to the formulation of an act is that the legislator demonstrates foresight and criminalises future innovative methods of violation and circumvention, so to speak, in advance, preventing gaps in the law. This also ensures that regulatory sanctions legislation and legislation on liability for violations keep pace with each other. Sanctions legislation is progressing, the types and content of restrictive measures are constantly expanding, and criminal law is changing post facto, as a result of which serious violations of restrictive measures may remain unpunished for a long time.

The main drawbacks of the most general wording, such as "sanctions violation," are a significantly lower degree of legal certainty and the risk of potential inconsistency with the provisions of the Directive on the definition of criminal offences. Since the latter, in Article 3, provides an exhaustive list of eight types of violations and four types of circumvention, it is not clear that all 12 types of acts will be recognized under the national law of a Member State as criminal offences. The greatest doubts in this case arise as to whether such wording ensures the criminalisation of circumvention of sanctions, since failure to report or declare funds and economic resources is not so much a consequence of a violation of a restrictive measure as a failure to comply with additional obligations provided for by acts (including regulations) in connection with the application of restrictive measures. According to another interpretation, this approach may be overly broad, i.e. violate the principle of proportionality, since the wording "violation of sanctions" can cover any, even minor (technical) provisions of the adopted acts (including regulations).

Ultimately, overly broad wording does not promote differentiation of liability, whereas Article 5 of EU Directive 2024/1226 provides for varying degrees of punishment for different types of violations and circumvention of sanctions. The generalized wording “violation of sanctions,” which covers different types of violations at the same time, negates the varying degrees of punishment. In such circumstances, the discretion of law enforcement agencies is expanded.

The second is a concrete (casuistic, typified) approach: it provides for the definition of specific types (kinds) of acts by listing them in the text of the law, usually leaving the list of violations exhaustive (not open-ended).

- Sweden: the repealed law previously provided for fairly general formulations of acts – "violation of the prohibition..." and "violation of the decision...". This was a reference norm that referred to other norms of the same law, which generally listed possible types of restrictions. The new law provides a much more specific description of acts, which is as close as possible to the literal reproduction of the provisions of Article 3 of the EU Directive: §3 and §4 provide for eight forms of violations corresponding to points (a) to (g) and (i) of Article 3(1) of the Directive, and § 5 contains four forms of circumvention of sanctions specified in points h(i)-(iv) of Article 3(1) of the Directive.

- Slovakia: as a result of transposition, the current Criminal Code of Slovakia provides an exhaustive list of violations of restrictive measures, which corresponds to the forms of violation and circumvention of sanctions defined in Article 3 of the Directive – all 12 types are defined in §§417a – 417d, most of which are listed in §417a. The wording of these types of violations is as close as possible to that contained in the Directive.

- Poland: The special law on sanctions in connection with the Russian Federation's aggression against Ukraine currently in force in Poland provides for the most casuistic and difficult to understand formulation of a criminal law prohibition, which is strictly linked in blanco to specific provisions of EU regulations that provide for certain restrictions, prohibitions and obligations (a sample excerpt from this law is provided in the Appendix to this analysis). The strict link to specific provisions of EU regulations is an example of excessive specificity, which leads both to problems with the general understanding of the criminal law prohibition and to the need for constant changes to criminal provisions: the expansion of sanctions and the emergence of new restrictions and obligations constantly necessitate amendments to criminal provisions. In this regard, the draft law proposes to adopt a descriptive definition of the conduct of persons and organisations that leads to criminal and administrative liability by adopting provisions that typify specific violations of sanctions in accordance with Article 3 of the Directive and, as a result, eliminate the need for permanent amendments. The draft defines the following types (forms) of acts: 8 forms of sanctions violations, which are reflected in Article 3(1)(a) – (g) and (i) of the Directive, are covered by Articles 30 – 35 of the draft and, in terms of content and wording, ensure maximum compliance; 4 types of circumvention of sanctions, which are reflected in Article 3(1)(h) of the Directive, are covered by Article 36 of the draft with maximum consistency with the relevant provisions of the Directive.

- Cyprus: the repealed Law of 25 April 2016 No. 58(Ι)/2016 contained in Article 4 a brief provision providing for an abstract formulation of the offence – criminal liability arose for violation of any of the provisions of EU Council decisions and regulations, without a list of specific forms of violations. The new Law provides an exhaustive list of specific forms of violation of restrictive measures, which corresponds as closely as possible in terms of content and wording to Article 3 of the Directive (a copy of its provisions): it distinguishes between 8 types of violations and 4 types of circumvention of restrictive measures, as in points h(i) – h(iv) of the Directive.

- Greece: the current Criminal Code provides for the most abstract formulation of the act – anyone who deliberately violates sanctions or restrictive measures applied to states, institutions or organisations, or natural or legal persons by Union regulations is punishable. The draft law provides an exhaustive list of specific forms of violation of restrictive measures, which corresponds as closely as possible in terms of content and wording to Article 3 of the Directive (in fact, it is a copy of it): it identifies 8 types of violations and 4 types of circumvention of restrictive measures.

- Malta: The current law punishes any person who acts in a manner that violates the rules adopted in accordance with this law, the EU Council Regulation or the UN Security Council Resolution, i.e. the wording of the act is clearly abstract. The draft law provides an exhaustive list of specific forms of violation of restrictive measures, which corresponds as closely as possible in terms of content and wording to Article 3 of the Directive (in fact, it is a copy of it): it identifies 8 types of violations and 4 types of circumvention of restrictive measures. At the same time, it is not clear from the published draft whether a violation or failure to comply with the conditions set out in the permits for activities, which in the absence of such a permit would constitute a violation of a restrictive measure, is an independent type of violation or a separate type of circumvention.

- Spain: the draft amendments to the Spanish Criminal Code provide for an exhaustive list of specific forms of violation of restrictive measures, which corresponds as closely as possible in terms of content and wording to Article 3 of the Directive: the eight types of violations and four types of circumvention defined in the Directive are proposed to be included in three articles of the Spanish Criminal Code, which is quite original:

– Article 604-2 provides for acts corresponding to the 7 forms of violations defined in points (a), (b), (d) – (g) and (i) of Article 3 (1) of the Directive, and 2 forms of circumvention defined in points (h) (i) – (ii) of Article 3 (1) of the Directive;

– Article 604-3 criminalises allowing a sanctioned entity that violates sanctions to enter or transit through Spanish territory (paragraph (c) of Article 3(1) of the Directive);

– Article 604-4 criminalises two forms of circumvention of sanctions relating to the obligation to notify/report (points (h) (iii) – (iv) of Article 3(1) of the EU Directive).

- Romania: the draft proposes a new Article 27-1 "Offences", which reproduces Article 3(1) of the Directive, with points (a) – (g) providing for eight forms of violation and points (h) to (k) providing for four forms of circumvention of sanctions (evasion).

- Finland: prior to transposition, the Finnish Criminal Code contained a general formulation – "anyone who violates or attempts to violate the legislation on..." (§ 3, section 46). After the addition of four new articles to the section of the Criminal Code (Violation of sanctions (§ 3a), Aggravated violation of sanctions (§ 3b), Negligent violation of sanctions (§ 3c) and Minor violation of sanctions (§ 3d)), the legal certainty of the criminal prohibition was significantly strengthened by listing all forms of violations provided for in Article 3 of the Directive, to a certain extent projecting its wording into the terminology adopted in Finland. The Finnish example of transposition of Article 3(1) of the Directive has two important features:

- among the forms of infringements, those that are not literally mentioned in Article 3(1) were also highlighted, in particular, infringement of a restrictive measure through the activities of a legal person, as well as by operating a means of transport or allowing it to enter or leave a territory or place (paragraphs 7 and 8, §3a);

- the list of forms (types) of violations remains non-exhaustive, as paragraph 10 §3a provides for acts of open content – violations in other ways, acting contrary to the prohibition imposed by a restrictive measure or sanction, or a notification or other obligation having an equivalent effect. In this form, not only are two forms of circumvention of sanctions (failure to comply with the obligation to notify and report) criminalised, but the list of serious violations is also left open. The other two forms of circumvention are listed in a separate paragraph of §3a.

The Finnish government based this approach on, on the one hand, the need for a general formulation, since it is impossible to describe all forms of violations exhaustively, and, on the other hand, the need to ensure legal certainty. Thus, despite the incompleteness of the list, it was possible to list the most common forms of violations/circumvention and avoid decriminalising acts that could fall outside the scope of criminal law if the government had proposed an exhaustive list of violations as outlined in Article 3(1) of the Directive.