>

Analytics>

Analysis of the practice of the High Anti-Corruption Court on the application of sanctions in the form of asset forfeiture to the state for 2022-2023Analysis of the practice of the High Anti-Corruption Court on the application of sanctions in the form of asset forfeiture to the state for 2022-2023

This study presents an analysis of 15 decisions of the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) and 2 decisions of the HACC Appeals Chamber imposing a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture. The think tank "Institute of Legislative Ideas" draws attention to the procedural and substantive peculiarities of the respective category of cases and offers recommendations aimed at ensuring compliance with the principles of the rule of law and fair trial in the consideration of these cases. In particular, the study covers the following issues: limitation period for filing a claim, time for trial, proper notification of the defendant, applicable standard of proof, prospective effect of the law, conditions for the forfeiture, proving the ownership or control over the assets and risks of violation of third party rights, etc.

Publisher: © CSO “Institute of Legislative Ideas” All rights reserved.

Authors: Tetiana Khutor, Bohdan Karnaukh, Andriy Klymosyuk, Taras Riabchenko

Summary

The adoption of the Law of Ukraine "On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving the Efficiency of Sanctions Related to the Assets of Certain Individuals" (Law No. 2257-IX), which entered into force on May 24, 2022, paved the way for the confiscation of assets of individuals and companies that contribute to the Russian aggressive war against Ukraine. This law introduced a new type of sanction - asset forfeiture.

The Institute of Legislative Ideas, having the relevant expertise in non-conviction based forfeiture (NCBF), has been studying the mechanism starting from the stage of drafting the relevant Law. After the Law was adopted and before the first lawsuits were filed, we provided recommendations on how to make the measure compatible with the standards of property rights protection, fair trial standards and in line with the ECtHR case law.

In this vein, the Institute of Legislative Ideas now analyzes the practice of applying the new sanction (in 15 judgments of the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) and two decisions of the HACC Appeals Chamber) in order to identify tendencies and spotlight bottlenecks in jurisprudence on the matter and to provide recommendations for improving the mechanism of forfeiture. The study addresses the following issues: limitation period for filing a claim, time for a trial, proper notification of the defendant, applicable standard of proof, effect of the law in time, proof of the conditions for the forfeiture, establishing the ownership of the assets and risks for third parties" rights etc.

1. Limitation period for filing a claim

In the HACC"s case law two different approaches may be encountered with regard to when exactly the three-month period for filing a claim starts to run: according to one it is the day when the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine (NCDC) freezes the defendant"s assets; according to the second, it is the day when all preconditions for the forfeiture eventuate. The limitation period should commence as soon as all the necessary preconditions for the forfeiture eventuate (assets freeze being just one of many), i.e. when all the facts that entitle the Ministry of Justice to file a claim has taken place.

2. Time of trial

Proper examination of evidence in this category of cases is not feasible within the ten-day period allotted by the Law. That is why the HACC had to deviate from the statutory time limit in order to ensure full and comprehensive study of the circumstances and proper assessment of the evidence submitted. However, such a deviation cannot be regarded as a violation of the guarantees of Article 6 of the ECHR, since according to the ECtHR case law, the paramount criterion on which the reasonable time of the trial depends is the complexity of the case.

3. Proper notification of the defendant

Given that "Ukrposhta" (Ukraine"s National Post) does not exchange mail with the Russian Federation, the acute issue that remains is the proper notification of defendants, without which it is impossible to comply with the guarantees of a fair trial. A possible solution to this problem could be the creation of a website (within the HACC"s or the NSDC"s web-platforms) specifically dedicated to announcements concerning sanctioned persons. On such a website, the relevant persons could track any changes in their status, including notifications of upcoming court hearings.

4. Standard of proof

In cases concerning forfeiture under Article 283-1 of the Code of Administrative Proceedings of Ukraine, a lower (civil-law) standard of proof applies. However, the definition of the standard in the current legislation does not accurately correspond to its true meaning. The civil-law standard of proof should be determined not by the relative strength of the one party's evidence compared to the other party's evidence (since in this case, as long as the defendant does not appear in the proceedings, the court would have to rule in favor of the plaintiff, no matter how weak the latter"s evidence was), but rather on the basis of the degree of conviction of the judge in the truth of the allegations relied upon by the plaintiff (the judge must be convinced that such allegations are more likely to be true than false). This standard is called the preponderance of evidence standard (aka balance of probabilities), or the 50+ standard.

The difference between the standard applicable in the cases at hand and the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard (which is applied in criminal cases) justifies why an administrative case concerning forfeiture can be tried before the sanctioned person is found guilty in criminal proceedings.

5. The effect of the law in time

The Law requires that confiscation can be applied only to persons whose assets were frozen after the forfeiture had been introduced into national legislation, i.e. after May 24, 2022. However, the date of assets freeze should not be relevant (provided that it took place after the entry into force of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions"), because when assessing the temporal effect of the provision on the forfeiture, the only factor to be taken into account is the date of the defendant's actions that justify the forfeiture.

6. Appeals

The right to appeal against a judgment in the relevant category of cases should be afforded not only to the parties, but also to third parties, which may often be the companies whose property or shares in the authorized capital the plaintiff seeks to forfeit to the state. Moreover, the tight deadline for appeal (five days) combined with the special rules on its calculation making it even shorter, and the fact that this deadline is not subject to renewal (Article 270(5) of the CAP) may be considered an obstacle that significantly hinders the practical exercise of the right of access to court by the person concerned.

7. The defendant's citizenship (residence)

In view of the imminent threat caused by the circumstances of the war in Ukraine, the provision of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions", according to which sanctions cannot be applied to Ukrainian citizens (except for those who carry out terrorist activities), seems unreasonable and probably discriminatory. This approach should be changed.

8. Regarding the preceding asset freeze

The HACC while considering a claim for the forfeiture assesses the lawfulness of the asset freeze that has to precede the forfeiture. Yet the position on the exact scope of the judicial review in this regard is unclear. The review remains mostly formal.

9. Regarding evaluative concepts

"Substantial threat" and "material assistance" as grounds for forfeiture are evaluative in nature. The very use of evaluative concepts per se cannot serve as a reason to criticize the Law, but the HACC should develop the proper criteria to assess the respective concepts.

And while there can hardly be any doubt that the threat to Ukraine's national security is substantial, the concept of "material assistance" may be subject to dispute. In general, the materiality of assistance should mean that the defendant's contribution to the "joint venture" of waging the aggressive war against Ukraine is tangible, noticeable, and significant in the context of the total efforts of all those involved in the aggression.

10. Establishing the ownership of assets

It is arguably the most difficult part in considering the relevant category of cases, due to the fact that not only the assets owned by the defendant directly, but also the assets that the defendant effectively controls without being the formal owner are subject to forfeiture.

To establish effective control, the following concepts should be utilized: ultimate beneficial owner; direct and indirect decisive influence; significant participation; indirect significant participation; control; related parties; chain of ownership of corporate rights in a company; affiliates; ownership structure of business entity.

The ownership structure often includes companies registered under foreign law. This can potentially create an opportunity to circumvent sanctions, provided that at least one of the companies in the chain is located in a jurisdiction that has not imposed sanctions on the defendant.

The court does not need to establish the fictitiousness of certain contracts (which were concluded to circumvent the sanctions), since the subject of proof is not the formal validity of a particular agreement, but the question of whether the defendant, despite the respective agreement (e.g. sale of shares in a company), retained the efficient control over the asset.

11. Protection of the rights of third parties

The application of a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture may potentially create risks of violation of the rights of third parties. For example, when the defendant's property is encumbered by the rights of third parties (pledge, mortgage, etc.), or when the asset to be confiscated belongs to a company in respect of which the defendant is the main, but not the only, beneficiary.In this case, the issue of protecting the rights of bona fide third parties becomes acute. Such protection can be ensured through providing some compensation mechanisms or saddling the state with the duty to purchase the shares of bona fide third parties upon their request, etc. However, one should not lose sight of the fact that such persons may also be indirectly related to the defendant, and it is subject to judicial determination. In this context, the burden of proof of one"s good faith may be allocated on those claiming violation of their rights by sanction measures, which would mean the introduction of a rebuttable presumption of bad faith of a third party.

In this context, the burden of proof of one"s good faith may be allocated on those claiming violation of their rights by sanction measures, which would mean the introduction of a rebuttable presumption of bad faith of a third party.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the cautions and recommendations expressed in this study are aimed at ensuring that the requirements of the rule of law are met when applying the sanction in the form of asset forfeiture. In order for such interference with the property rights to be compatible with fundamental human rights, it must (a) be lawful; (b) pursue a legitimate aim; and (c) be proportionate to the aim pursued. Moreover, in addition to the ECtHR case law on the right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions and fair trial standards, the High Anti-Corruption Court should also take into account international law on the protection of foreign investment. In this regard, attention should be paid to compliance with the requirements of "necessity" as defined in Article 25 of the Articles of the UN International Law Commission on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts.

Introduction

The adoption of the Law of Ukraine "On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving the Efficiency of Sanctions Related to the Assets of Certain Individuals" (Law No. 2257-IX), which entered into force on May 24, 2022, paved the way for the confiscation of assets of individuals and companies that contribute to the Russian aggressive war against Ukraine. This law introduced a new type of sanction - asset forfeiture.

The Institute of Legislative Ideas analyzes how the new sanction is applied in jurisprudence of the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) in order to identify some tendencies in case law and develop recommendations on how to warrant compliance with the principles of the rule of law and fair trial in the relevant category of cases.

Methodology

This study offers an analysis of fifteen HACC judgments applying the sanction provided for in clause 11, part 1, Article 4 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions", which had been delivered as of March 1, 2023. These are the judgments in the following cases:

Case of YEVTUSHENKOV V.P.

Case of FALALEYEV A. P.

Case of POLUKHIN O.M.

Case of YANUKOVYCH V.F.

Case of TORKUNOV A.V.

Case of LYABIKHOV R.P.

Case of PAIKIN B.R.

Case of SHELKOV M.YE.

Case of KOLBIN S.M.

Case of KOVITIDI O.F.

Case of BAKHAREV K.M.

Case of AKSAKOV A.G.

Case of DERIPASKA O.V.

Case of CHERNIAK O.Y.

Case of GINER E.L.

Case of ROTENBERG A.R. et al.

Case of BABASHOV L.I.

The cases were analyzed through the lens of compatibility of the measure with the right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions (Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the ECHR), fair trial standards (Article 6 of the ECHR) and norms of international investment law. The first part of the study focuses on preliminary (procedural) issues, such as the limitation period for filing a claim, duration of trial, proper notification of the defendant, the applicable standard of proof and the effect of the law in time. The second part of the study deals with the substantive issues, viz the conditions necessary for the imposition of the relevant sanction. In particular it addresses the defendants' citizenship (residence) requirement, the preceding assets freeze, establishing the ownership of the assets, the use of evaluative concepts and protection of third party rights.

Procedural issues

Limitation period for filing a claim

The procedural peculiarities of trying the claims for asset forfeiture are provided for in Article 283-1 of the Code of Administrative Procedure of Ukraine (hereinafter – CAP). Yet, the Article is silent on the time limit within which the Ministry of Justice may file a claim with the court. Therefore, the general rule applies. It is enshrined in of para 2, part 2, Article 122 CAP:

"A three-month period shall be established for a public authority to apply to an administrative court, which, unless otherwise provided, shall be calculated from the date of occurrence of the grounds giving the public authority the right to file the claims specified by law".

It follows from the above provision that the Ministry of Justice is given three months to file a lawsuit with the court. But when exactly does the three-month period starts to run? In the case law of the HACC two different answers may be found. Thus, in some cases(1), the HACC notes that this period should start from the date when the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC) freezes the assets of the individual concerned. For example, in the Polukhin case, the HACC noted:

"for the plaintiff, the three-month period for applying to the court began from the date of imposition by the NSDC of the sanction in the form of an indefinite freeze of the defendant's assets...".

On the contrary, in some other cases(2), the HACC points out that the starting point should not be the NSDC"s decision, but the day when the Ministry of Justice collected sufficient evidence to justify the forfeiture. For example, the Torkunov case reads:

"the authorized subject obtains the right to file the claim not from the moment when President"s Decree enacts the relevant decision of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine [on asset freeze], but from the moment when all the conditions for the imposition of the sanction are established, including, the ownership of certain property (assets) by the person; at the same time filing a claim to the court is limited to the period of martial law".

The latter position prevails in the HACC"s case law and it is more in line with the wording used in Article 122 CAP providing that the countdown starts when all the grounds entitling the public authority to file the claim occur. The decision of the NSDC on assets freeze is not the sole, but only one of the grounds (conditions)(3) for the assets forfeiture.

The assets freeze implemented by the decision of the NSDC is personal: it applies to a certain person without specifying the list of assets that are subject to freeze (the sanctioned person named in the NSDC"s decision is deprived of the right to use and dispose of his/her property "wherever it is located and whatever it consists of"). In contrast, the asset forfeiture applies to the specifically identified assets. Accordingly, before filing a claim, the Ministry of Justice must establish which assets belong to the person concerned (directly or indirectly), and it requires a thorough investigation involving a number of other state authorities.

Apart from that, forfeiture may be applied only as long as the person has created a significant threat to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine or has materially contributed to it.

Therefore, the time for filing a claim with an administrative court cannot start running before the Ministry of Justice establishes the range of assets controlled by the sanctioned person and receives confirmation that the person has created or materially contributed to a significant threat to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine. These two circumstances are among the conditions that entitle the authorized body to file the claim, and therefore, in accordance with the provisions of Art 122 CAP, the limitation period is dependent on them and shall not start running before they occur.

On the one hand, it may be objected that such an approach equals to the Ministry of Justice not being limited in time at all. However, in Bogdel v. Lithuania, a similar approach (that the limitation period for the state claims shall be calculated from the day when the relevant body "obtained sufficient evidence to prove that the public interest has been violated") was not considered a violation of the ECHR(4). Secondly, additional time limits are established in para 2 part 1 Art 5-1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions", according to which a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture shall be applied only during the period of martial law.

The limitation period should commence as soon as all the necessary preconditions for the forfeiture eventuate (assets freeze being just one of many), i.e. when all the facts that entitle the Ministry of Justice to file a claim have taken place.

1. See the cases of Polukhin and Falaleyev.

2. See the cases of Yanukovych, Kolbin, Torkunov, and Paikin.

3. For a detailed list of grounds, see paragraph 7.9 of the Deripaska Case.

4. Bogdel v. Lithuania, no. 41248/06, ECHR, 26 November 2013.

Time for trial

Reasonable time of a trial is an important element of the right to a fair trial guaranteed by Art 6 of the ECHR(5). Usually it is the excessive length of a trial that causes complaints. However, in the case of asset forfeiture the situation is the opposite: the time limit for trial set by the law seems to be too short for the cases of this level of complexity.

According to part 4 Art 283-1 CAP:

"The case on the application of a sanction provided for in clause 11 part 1 Art 4 of the Law of Ukraine “On Sanctions” shall be decided by a panel of three judges of the High Anti-Corruption Court within 10 days from the date of receipt of the statement of claim by the court."

According to clause 11 part 1 Art 4 CAP:

"reasonable time is the shortest period for consideration and resolution of an administrative case sufficient to warrant timely (without unjustified delays) judicial remediation of violated rights, freedoms and interests in public law relations".

At the same time, it is safe to say that forfeiture cases are among the most complex ones: they require examination of a huge amount of evidence, consideration of numerous international law provisions, assessment of global processes, and investigation of complex ownership structures and corporate relations, which often involve legal entities registered under foreign law. For example, in the Deripaska case, the list of assets claimed in the lawsuit amounted to 359 items, including both movables and immovables, as well as corporate rights. The court had to establish the ownership structure and identify the ultimate beneficiaries of more than ten companies. At the time of the ruling, the case file amounted to 18 volumes.

Proper examination of evidence in such complex cases is impossible within a ten-day period. Therefore, in the vast majority of such cases, the HACC had to deviate from the statutory time limit for consideration of the case in order to ensure full and comprehensive clarification of the circumstances and proper assessment of the evidence. So far the average time for consideration of this type of case in the first instance is 19 days. Moreover, in 10 out of 15 cases, the trial time exceeded 10 days. The cases of Kolbin (39 days), Deripaska (35 days), and Shelkov (33 days) took the longest. The fastest were the cases of Kovitidi, Giner, Polukhin and Aksakov (7 days each).

The deviation from the ten-day limit can hardly be regarded as a violation of the guarantees of Art 6 of the ECHR, since according to the ECtHR"s case law, the paramount criterion on which the reasonable duration(6) of the trial depends is the complexity of the case, which may be related to large amount of evidence, the need to obtain an expert opinion or evidence from abroad, the complexity and significant number of facts, a large number of persons involved in the case, the need to involve witnesses, translators, the complexity of legal issues, for example, the need to apply foreign law, etc. Almost all the factors are present in the cases considered.

As the HACC noted in the Deripaska case:

"4.6. The Court believes that the statutory ten-day term for consideration of this category of cases could not have ensured the completeness and objectivity of the trial, proper adversariality (the opportunity to know and comment on all evidence submitted to influence the court's decision, to have sufficient time to familiarize oneself with the evidence, the opportunity to provide evidence, etc.) Therefore, despite the fact that the Court exceeded the statutory time limit for consideration of the administrative case, the case was considered within a reasonable time that warranted the rights of the parties and clarification of all the relevant circumstances of the case".

Moreover, strict adherence to the ten-day period set by the law could be considered a violation of Art 6 of the ECHR. After all, such "hasty justice" could mean insufficient thoroughness of the court, failure to allow the parties the necessary time to make their case and the overall superficial nature of the trial. Therefore, in order to eliminate the ambiguity of the situation (where the HACC has to deviate from the statutory time limit in order to comply with the fair trial standards), it is advisable to amend part 4 Art 283-1 CAP and extend the term for consideration of the relevant category of cases.

Proper notification of the defendant

Fair trial standards require that a party to the proceedings be given a real opportunity to present its case before the court and submit evidence supporting it on equal terms with the opponent. For this opportunity to be real, first and foremost the party has to be aware that a case against it will be tried by the court. Therefore, it is crucial for the rule of law to be respected that the defendants are duly notified of the proceedings and given a real opportunity to participate in the trial.

The general provisions on notifying the parties are set forth in Ch 7 "Court Summonses and Notices" CAP. Under par 3 Art 124 CAP a summons usually is sent either to the official e-mail address(7), if any, or by registered mail or courier with a return receipt(8).

However, taking into account that non-residents rarely have their accounts in the Ukrainian Judicial Information Telecommunication System, as well as the fact that "Ukrposhta" (Ukraine"s National Post) halted exchanging mail with the Russian Federation (in accordance with the Universal Postal Conventions and Regulations) and does not carry out postal exchange between the mainland of Ukraine and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the legislator has provided special rules for notifying defendants in the cases concerning forfeiture under the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions".

According to parts 1 and 2 of Article 268 CAP:

"1. In cases specified in Articles 273-277, 280-283-1, 285-289 of this Code, the court shall immediately notify the defendant and other parties to the case of the filing of a statement of claim and the date, time and place of the hearing by sending the text of the summons to the official e-mail address, and in its absence - by courier or by telephone, fax, e-mail or other technical means of communication known to the court.

2. A party to the case shall be deemed to have been duly notified of the date, time and place of the hearing specified in part one of this Article from the moment such notice is sent by a court officer, which the latter makes a note of in the case file, and (or) from the moment the court publishes the relevant decision to open proceedings on the web portal of the judiciary of Ukraine specifying the date, time and place of the hearing."

Unlike the general rules, this article provides for the possibility to notify defendants in this category of cases by telephone, fax or e-mail. Moreover, in the event that even these options are unavailable, notification may be made through publication on the official web portal of the judiciary of Ukraine.

The HACC is quite meticulous about notifying defendants and strives to take all possible measures to ensure that the defendant is duly informed of the proceedings. Often, the HACC does not limit itself to single method of notification, but instead uses all possible methods (the judiciary's web portal, an email address known to the court), including even sending messages on Facebook(9). Given that the sanctioned persons hold positions in various institutions and organizations, the use of the so-called "corporate" email address of a person in the relevant institution or organization also seems to be a viable option.

Sometimes, the HACC also notes that, given the high-profile nature of the case, news outlets may also serve as an additional source of awareness for the defendant (since the relevant cases receive wide coverage in the media(10).

At the same time, it seems appropriate to consider the possibility of creating a website specifically dedicated to announcements concerning sanctioned persons. On such a website, interested persons could track any changes in their status, including notifications of upcoming court hearings.

The closely related issue is ensuring that the defendants willing to participate in the proceedings have a real opportunity to do it. Although participation in the proceedings usually means appearance in the courtroom, Art 195 CAP allows the parties to participate in the court hearing via videoconference. Therefore, even though the defendants may have concerns about their safety in Ukraine, they are nevertheless given the real chance to present their case before the court. In the Yanukovych case, the HACC noted that the defendant was aware of this option (to participate in the hearing via videoconference), since his defense counsel had filed the motion (to use videoconference tools) in another case.

7. Official email address is the email address specified by the user in the Electronic Cabinet of the Unified Judiciary Information Telecommunication System.

8. There are other options, but they are conditional on the consent of the party. See: Article 129 CAP.

9. See the cases of Lyabykhov and Paykin.

10. See the cases of Yanukovych, Lyabykhov and Paykin.

Standard of proof and relation to criminal proceedings

The applicable standard of proof is an important trait of cases concerning assets forfeiture under the Law "On Sanctions".

According to part 6 Art 283-1 CAP: "The court shall rule in favor of the party whose evidence is more convincing than the evidence of the other party".

This provision is often associated with the standard of proof. However, it is not consistent with what is meant by the standard of proof in legal doctrine(11).

A judge decides a question of fact on the basis of his or her inner conviction, which he or she forms through examining the evidence presented by the parties. In order to find that a certain fact has indeed taken place, a judge must gain a certain level of conviction that it is the case. The standard of proof is the threshold value of conviction that is considered sufficient for the judge to find a certain fact proven.

In the doctrine of law, two standards of proof are distinguished: proof beyond reasonable doubt and preponderance of the evidence, also known as "balance of probabilities". The former applies in criminal cases while the latter applies in civil cases.

The standard beyond reasonable translates to numbers as 90% or more confidence. It means that it is not enough when judge is slightly more inclined towards the statement being true than towards it being false; instead, a strong conviction that the statement is true is required; any doubts that from the perspective of common sense and everyday life experience cast a shadow on the credibility of the statement must be excluded(12).

In contrast, the civil law standard (balance of probabilities) is expressed as a confidence of more than 50%. In other words, for a judge to find a fact proven, it is enough for him or her to believe that it is more likely that the fact occurred than that it did not(13).

Thus, the criterion by which the standard of proof is determined should be the level of judge"s conviction that a certain fact has occurred, and not – as follows from part 6 of Art 283-1 CAP - the simple comparison of probative value of one party"s evidence to the probative value of other party"s evidence. The literal text of the Article would mean that even when the evidence submitted by one party is utterly unconvincing, the court must nevertheless rule in favor of that party if the evidence of the other party was even less convincing. Moreover, if the other party does not participate in the proceedings at all (as is often the case in trials under Art 283-1 CAP), and does not submit any evidence whatsoever, no matter how poor the evidence of the claimant is, the court must grant the claim.

However, this interpretation of the standards of proof is clearly erroneous. Therefore, part 6 Art 283-1 CAP should be amended to correctly reflect the lowered, civil standard of proof for this category of cases.

This is of fundamental importance, since the standard of proof is closely related to another issue that is acutely relevant to this category of cases, namely, the issue of correlation between cases under Art 283-1 CAP and criminal cases against sanctioned persons.

The actions that allow the forfeiture under Art 5-1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" to a large extent correspond to the corpus delicti of criminal offenses (Section I of the Special Part of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, "Crimes against the Fundamentals of National Security"). However, it is important to emphasize that the asset forfeiture set forth in Art 4 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" does not require a prior conviction of the defendant for committing the relevant crimes.

This independence (of proceedings under Art 283-1 CAP from criminal proceedings) is conceivable precisely due to the fact that different standards of proof apply in these two types of proceedings: in criminal proceedings, a person's guilt must be proved beyond reasonable doubt (i.e., the judge must be 90 percent or more confident that the accused committed the offence), while in civil proceedings it is sufficient to prove that the probability of defendant committing the impugned actions is higher than the probability of the opposite (i.e., the judge must be 50+ percent confident)(14). This approach is typical for the concept known in foreign countries as "Non-conviction based forfeiture" (NCBF).

In most of the cases that the HACC has considered so far (except for the Yanukovych case), the defendants had not been previously brought to criminal liability.

Therefore, an accurate conceptualization of the standard of proof applicable in these cases will allow to coherently distinguish forfeiture claims under the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" from criminal charges.

This is also related to the appropriateness of the evidence collected in criminal proceedings (that are not yet completed) being used in cases under Art 283-1 CAP.

For example, in the Deripaska case, the counsel, objecting to the claim, pointed out that the information obtained in criminal proceedings has no probative value for the court in the administrative case, since no verdict has been reached in criminal case yet(15).

The HACC rejected the argument stating that

"the information obtained during the pre-trial investigation may be accepted as evidence in the administrative case and is subject to evaluation on par with other evidence. In this case, the set of documents containing the information established during the pre-trial investigation is relevant to administrative case at hand in the context of the credibility of evidence, therefore, it is examined and evaluated by the Court in conjunction with other evidence regardless of the [absence of] final court decisions in the criminal proceedings"(16).

In the case of Rotenberg et al. the HACC explained that the procedural documents of the prosecution (in particular, a notice of suspicion) cannot be used as evidence for the purposes of an administrative case, as they reflect the position of one of the parties to the criminal proceedings, and thus have no probative value. At the same time, evidence collected in a criminal case (expert opinions, seized/requested documents (electronic documents), including those whose content is reflected in the protocols of their review, which were obtained within the framework of the relevant criminal proceedings) are admissible evidence and may be used in an administrative case.

Once again, the above positions demonstrates the need for a clear doctrinal and normative "separation" of administrative proceedings under Art 283-1 CAP and criminal proceedings against the same person.

In the context of separation of administrative proceedings and criminal prosecution, it is also worth considering whether the relevant proceedings on confiscation (as provided for by the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions") can be regarded as criminal prosecution in the context of Article 6 of the ECHR? This question arises because the concept of "criminal prosecution" in Article 6 of the ECHR is autonomous, i.e., it does not depend on the national categorization of the relevant measure as criminal or non-criminal. In other words, the ECHR may recognize certain proceedings as criminal charges even if they are not recognized as such under the national law of the country where the proceedings are brought.

The criteria that the ECtHR takes into account when determining whether a certain proceeding is a criminal charge were formulated in Engel and Others v. the Netherlands, 1976 (§§ 82-83): (1) classification under national law; (2) nature of the offense; and (3) severity of the punishment.

In the case of Rotenberg et al. the HACC rightly argues that the claims of the Ministry of Justice for the application of a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture cannot be considered a criminal charge. The severity of the relevant sanction does not reach the level of criminal punishment, and the entire sanction mechanism is not so much criminal as political and economic in nature: it aims to change the behavior of persons "whose will may affect and/or affects the political decision-making to end the armed aggression". Furthermore, the reach of this sanction is limited to those whose assets have previously been frozen (unlike the criminal law, which has a universal application).

13. See: Karnaukh, B. Standards of Proof: A Comparative Overview from the Ukrainian Perspective. Access to Justice in Eastern Europe, 2021, 2(10), 25–43.

15. Deripaska case, para 5.7.

16. Deripaska case, para. 7.15.15.

Effect of the law in time

An element of the internal morality of law(17) is the principle that laws usually should not have retroactive effect. This means that the adopted law applies only to facts that occur after its entry into force.

The principle is reflected in Art 58 of the Constitution of Ukraine, which states:

"Laws and other regulatory legal acts shall not have retroactive effect, except when they mitigate or cancel liability of a person.

No one may be held liable for acts that were not recognized by law as an offense at the time of their commission."

Since the asset forfeiture has to be preceded by the asset freeze, the following events may be considered relevant (in terms of preventing the retroactive effect of the law): defendant"s actions entailing the asset freeze; decision by the National Security and Defense Council on assets freeze; defendant"s actions entailing asset forfeiture.

It is worth noting that the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" came into force on September 12, 2014. However, the sanction in the form of asset forfeiture was introduced into the Law much later - as a result of the adoption of the Law of Ukraine "On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving the Efficiency of Sanctions Related to the Assets of Certain Individuals" (Law No. 2257-IX), which entered into force on May 24, 2022.

Under Art 6 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions", assets forfeiture may be applied only to persons whose assets were frozen after the new sanction (forfeiture) was introduced into national legislation, i.e. after May 24, 2022.

Since the provision on asset freeze has been in force since 2014 (when the Law was initially adopted), the actions of the person that led to the assets freeze may have taken place before May 24, 2022(18), but the NSDC"s decision and actions that serve as the reason for forfeiture must take place after that date.

In its judgments, the HACC emphasizes that:

"The above provision [on assets freeze], in the unchanged edition, has been in force from the date of entry into force of the said law on Sep 12, 2014 to the present day (without any amendments to it). In the Court's opinion, the above indicates that the defendant, starting from Sep 12, 2014, should have been aware that in case of committing the specified actions, he could be subject to sanctions from the state of Ukraine, including the freezing of assets.

<...>

Since the provisions of Art 58 of the Constitution of Ukraine also apply to clause 11 part 1 Art 4 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions", the Court must make sure whether the defendant's constituting the ground for asset forfeiture under Art 5-1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" existed or continued to exist after the entry into force of the amendments to the Law, namely after May 24, 2022"(19).

In most cases, the actions that justify forfeiture are systematic or ongoing. Therefore, they may commence before May 24, 2022 provided that they continue after that date. Thus, proper attention should be paid to the scrutiny of episodes that occur after the said date and confirm that the person has not reconsidered his or her stance and continues to actively support Russian aggression.

However, the panel in the case of Rotenberg et al. held a different view, concluding that forfeiture is available even if the defendant's unlawful actions occurred before May 24, 2022. This conclusion was based on the fact that the prohibition of aggressive war is a peremptory norm of international law (jus cogens). This norm, as the Court noted,

"was introduced and recognized by the international community long before the invasion of the territory of Ukraine by the armed forces of the Russian Federation, and therefore was known in advance to all persons who participated in the decision to start an international armed conflict, supported or justified it, wherever they were and under the jurisdiction of whatever state they were at the time of the commission of these actions"

And since the norms of international treaties to which Ukraine is a party automatically become part of national law, it should be recognized that the norm prohibiting aggressive war and any form of aiding and abetting such a war existed in national law long before May 24, 2022. Accordingly, the imposition of a sanction for aiding and abetting an aggressive war cannot be considered a punishment for actions that were not recognized as illegal at the time of their commission.

In addition to this discrepancy, there is another aspect that remains unresolved.In particular, what if the asset freeze was applied to a person before May 24, 2022, but later the term of the freeze was extended by a new decision made after that date, or if a later decision amended the content of the restrictive measure.

It was the case with regard to Yanukovych. Initially, the assets freeze was imposed on him by the Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 15-1/2021 dated April 9, 2021. However, subsequently, by the decision of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine dated October 12, 2022 (enacted by the Decree of the President of Ukraine dated October 12, 2022 No. 694/2022), the previously imposed sanction was canceled with the simultaneous imposition of a new freeze. The HACC concluded that forfeiture can be applied, since the second freeze took place after May 24, 2022.

However, in our opinion, in the context of retroactive effect of the law, the focus should not be placed on the date when the assets were frozen - it should not matter, because the sanction that was introduced into the legislation later is forfeiture. Therefore, what matters is the date when the actions of a person justifying forfeiture took place. They have to take place after the forfeiture was introduced in the Law, regardless of when assets freeze was imposed. Therefore, it seems appropriate to amend Art 6 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" in the relevant part.

17. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

18. As long as it is after September 12, 2014 (when the Law "On Sanctions" came into force).

19. See the cases of Yanukovych, Kolbin, Torkunov, and Lyabykhov.

Дія закону в часі

Елементом внутрішньої моралі права(21) є принцип, згідно з яким закони, за загальним правилом, не повинні мати зворотної дії в часі. Це означає, що ухвалений закон розповсюджує свою дію тільки на правовідносини, які виникли після набрання ним чинності.

Цей принцип дістав відображення у ст. 58 Конституції України, відповідно до якої:

«Закони та інші нормативно-правові акти не мають зворотної дії в часі, крім випадків, коли вони пом'якшують або скасовують відповідальність особи. Ніхто не може відповідати за діяння, які на час їх вчинення не визнавалися законом як правопорушення».

Оскільки стягнення активів в дохід держави можливе лише за умови, що активи відповідної особи попередньо були заблоковані (абз. 2 ч.1 ст. ст. 5-1 ЗУ «Про санкції»), хронологічно важливими в контексті дії закону в часі вважаються такі події: вчинення особою дій, що дають привід для блокування активів, прийняття рішення РНБО про блокування активів, вчинення особою дій, які визнаються підставою для стягнення активів у дохід держави.

Також важливо враховувати, що ЗУ «Про санкції» набув чинності 12.09.2014 року. Проте, санкція у виді стягнення активів у дохід держави з’явилася в ньому значно пізніше, - внаслідок прийняття ЗУ «Про внесення змін до деяких законодавчих актів України щодо підвищення ефективності санкцій, пов’язаних з активами окремих осіб» (Закон № 2257-IX), який набрав чинності 24.05.2022 року.

У статті 6 ЗУ «Про санкції» законодавець визначив, що санкція, передбачена п. 11 ч.1 ст. 4 ЗУ «Про санкції», може застосовуватися виключно до осіб, чиї активи були заблоковані після того, як відповідна санкція була запроваджена в національне законодавство, тобто після 24.05.2022 року.

Таким чином, оскільки норма про блокування активів була наявною в законі від самого його прийняття, то дії особи, що потягли за собою блокування активів, можуть мати місце до 24.05.2022 року(22), однак рішення РНБО та дії, що слугують підставою для стягнення активів, повинні мати місце після цієї дати.

ВАКС у своїх рішеннях наголошує, що:

«Вищенаведена норма [про блокування активів], у цій редакції, діє від часу набрання чинності згаданого закону - 12.09.2014 і по сьогоднішній день (без внесення будь‑яких змін до неї). Наведене, на переконання суду, свідчить про те, що відповідач, починаючи з 12.09.2014, мав бути обізнаним, що у випадку вчинення вищезазначених дій, відносно нього можуть бути запроваджені санкції з боку держави України, зокрема блокування активів.

<…>

Оскільки положення статті 58 Конституції України поширюються і на підпункт 1-1 частини 1 статті 4 Закону України «Про санкції», суду необхідно перевірити, чи вбачаються у діях відповідача підстави, передбачені частиною першою статті 5-1 Закону України «Про санкції», які виникли або існували та продовжили існувати після набуття змін до цього Закону (набуття чинності Закону № 2257‑IX), а саме станом на 24.05.2022»(23).

Здебільшого дії, які слугують підставою для застосування санкційної конфіскації, мають систематичний або триваючий характер. У зв’язку з цим, вони можуть брати свій початок і до 24.05.2022, за умови, що вони продовжуються і після цієї дати. Тому ретельну увагу належить приділяти дослідженню епізодів, які мали місце після відповідної дати і підтверджують, що особа не переглянула своєї позиції і продовжує активно підтримувати російську агресію. Однак колегія у справі Ротенберта та ін. висловила іншу точку зору, дійшовши висновку, що стягнення активів у дохід держави можливе навіть тоді, коли протиправні дії відповідача мали місце до 24.05.2022 року. Такий висновок було обґрунтовано тим, що заборона агресивної війни - це надімперативна норма міжнародного права (jus cogens). Ця норма, як зауважив Суд,

“була запроваджена та визнана міжнародною спільнотою задовго до вторгнення збройних формувань Російської Федерації на територію України, а тому була заздалегідь достеменно відомою всім особам, які брали участь в ухваленні рішення про початок міжнародного збройного конфлікту, підтримували або виправдовували його, де б вони не знаходились та під юрисдикцією якої б держави вони не перебували на момент вчинення цих дій”.

І оскільки норми міжнародних договорів, учасницею яких є Україна, автоматично стають частиною національного права, слід уважати, що норма, яка забороняє агресивну війну та будь-які форми пособництва такій війні, існувала в національному праві задовго до 24.05.2022 року. Відповідно, застосування санкції за сприяння агресивній війні не може вважатися покаранням за дії, які на момент їхнього вчинення не визнавались протиправними.

Окрім цієї розбіжності є ще один аспект, який залишається невирішеним. Зокрема, як бути, якщо блокування активів було застосоване до особи до 24.05.2022 року, але згодом, строк дії блокування було подовжено новим рішенням, ухваленим після цієї дати, або ж коли пізнішим рішенням було внесено зміни до формулювання змісту обмежувального заходу.

Так, зокрема, сталося у справі Януковича. Спочатку блокування активів було застосовано до нього Указом Президента України від 09.04.2021 № 151/2021. Однак згодом рішенням РНБО від 12.10.2022 (введеним в дію Указом Президента України від 12.10.2022 № 694/2022) застосована раніше санкція була скасована із одночасним уведенням в дію нового блокування. ВАКС дійшов висновку, що стягнення активів в дохід держави може бути застосоване, оскільки вдруге блокування активів відбулося після 24.05.2022 року.

Разом із тим, на наш погляд, у контексті зворотної дії закону в часі, фокус уваги має бути зосереджений не на тому, коли відбулося блокування активів, – це не повинно мати значення, адже санкція, що була запроваджена в законодавство пізніше – це саме стягнення активів. Відтак, головне те, що дії особи, які є підставою для стягнення активів, повинні мати місце після того, як можливість такого стягнення була запроваджена в законодавство, безвідносно до того, коли саме було застосовано блокування. Тому видається доречним внести зміни у відповідній частині до статті 6 ЗУ «Про санкції».

(21) Fuller, L.L. The Morality of Law. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

(22) Але після 12.09.2014 року (набрання чинності ЗУ «Про санкції»).

(23) Див. справи Януковича, Колбіна, Торкунова, Лябихова.

Appeals

According to the general rules of administrative proceedings (Article 293 CAP), all participants in the case, i.e. both parties (claimant and defendant) and third parties, have the right to appeal. At the same time, according to Article 283-1 CAP, defining the peculiarities of proceedings in cases on imposition of sanctions, the right to appeal is provided only for the parties (part 8).

It seems that this gap should be corrected. Confiscation cases under the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" often involve third parties. In particular, they may be the companies themselves, whose property or shares in the authorized capital the plaintiff claims to recover for the benefit of the state. For example, in the Deripaska case, there were 14 third-party companies.

In the Rotenberg et al. case, there were 14 third parties, including both companies and individuals. In the Yevtushenkov case, there were 6 third parties. Third parties in the concerned category of cases, as well as under the general rule, should have the right to appeal against the judgment in the case in which they participated.

With regard to the appeal, there is also the issue of calculating the deadlines. According to part 8 of Article 283-1 of the CAP

"An appeal against the judgment of the High Anti-Corruption Court may be filed by a party to the Appeals Chamber of the High Anti-Corruption Court within five days from the date of its announcement. Persons who were not present at the announcement of the said decision have the right to appeal it within five days from the date of publication of the decision on the official website of the High Anti-Corruption Court."

Under the general rule of part 9 of Article 120 CAP

"The deadline is not missed if, before its expiration, the statement of claim, complaint, other documents or materials or money are submitted by post or transferred by other appropriate means of communication."

However, this rule does not apply to cases concerning the imposition of a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture. This is expressly stated in part 1 of Article 270 CAP. This exception gives rise to the conclusion that within the five-day period established by law, the appeal must not only be sent to the post office for submission to the court, but must be already received by the court directly. This was the conclusion of Judge Bondar S.B. in his dissenting opinion in the Giner case. The court decision in this case was announced on February 27, 2023. The appeal sent by mail on March 01, 2023, was received by the court on March 07, 2023. The Appeals Chamber decided to open the appeal proceedings. Judge Bondar S.B. disagreed with the majority opinion, arguing that the time limit for appeal had been missed.

However, in our opinion, the tight deadline for appeal combined with the special rules for its calculation making it even shorter, and the fact that this deadline is not subject to renewal (part 5 of Article 270 CAP), may be regarded as an obstacle that significantly hinders the practical exercise of the right of access to court by the person concerned.

Про юрисдикційний імунітет

В одній зі справ(24), які розглянув ВАКС, відповідачем був орган іноземної держави, а саме – Міністерство оборони Республіки Білорусь. Ішлося про конфіскацію авіаційного двигуна, який Міністерство оборони Республіки Білорусь передало за договором українському заводу АТ «Мотор Січ» для проведення капітального ремонту.

Дивно те, що ВАКС, розглядаючи цю справу, не торкнувся питання юрисдикційного імунітету іноземної держави. Суд дійшов досить неочікуваного висновку, що Міноборони РБ «є іноземною юридичною особою в розумінні Закону України «Про санкції». Суд наче закрив очі на той факт, що це не просто юридична особа публічного права, а орган державної влади Білорусі. Між тим, стаття 2 Конвенції ООН про юрисдикційні імунітети держав та їхньої власності під «Державою» розуміє в тому числі державні органи.

Що стосується ЗУ «Про санкції», то частина друга статті 1 цього Закону дійсно передбачає можливість застосування санкцій до іноземної держави, однак слід мати на увазі, що в Закон охоплює різні види санкцій (див. ст. 4). Усі вони, крім однієї – стягнення активів в дохід держави – застосовуються в позасудовому порядку. І щодо всіх таких санкцій, крім однієї, положення про те, що вони можуть бути застосовані до іноземної держави, – справедливе. Утім, як щойнодеться про судовий порядок – мають бути враховані правила юрисдикційних імунітетів держав. Загальне правило при цьому зводиться до того, що одна держава не може бути відповідачем у справі, яку розглядає національний суд іншої держави.

Верховний Суд торкався цього питання у справах про відшкодування шкоди, завданої війною, і дійшов висновку, що Російська Федерація не може посилатися на імунітет з огляду на так званий деліктний виняток(25), що передбачений як у Конвенції ООН, так і в Європейській конвенції про імунітет держави (European Convention on State Immunity). Утім справи, які розглядає ВАКС не є справами із деліктів, і тому можливість розгляду українським судом справи за позовом до іноземної держави, потребує окремого обґрунтування.

(24) Справа Міноборони Республіки Білорусь

Conditions for the forfeiture

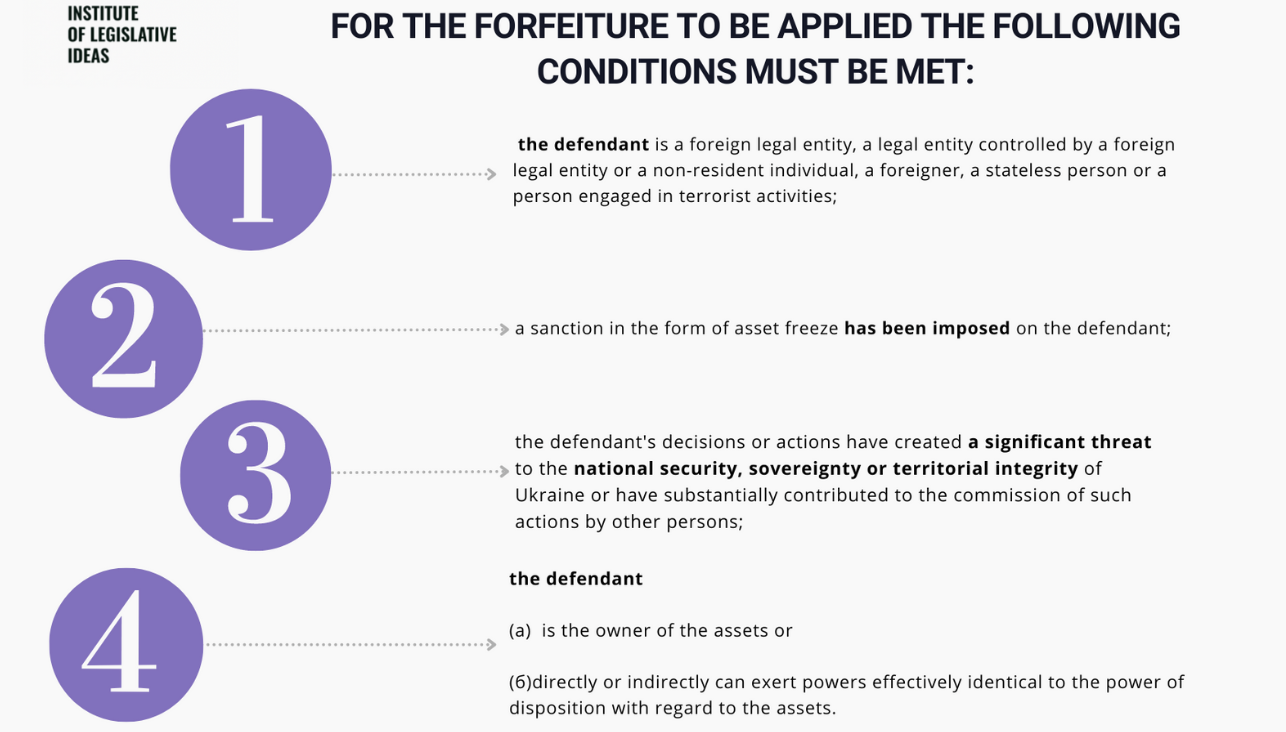

Forfeiture can be applied only during the martial law regime. While establishing the above conditions, the HACC, taking into account the ECtHR case law, also determines whether the application of the sanction will contribute to the achievement of the goals set out in Art 1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" (protection of national interests, national security, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, battling terrorism, as well as prevention of violations, restoration of violated rights, freedoms and legitimate interests of Ukrainian citizens, society and the state), as well as whether the application of the sanction is proportionate to the said goal.

Regarding the citizenship (residence) of the defendant

According to part 2 Art 1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions":

"Sanctions may be imposed by Ukraine against a foreign state, a foreign legal entity, a legal entity controlled by a foreign legal entity or a non-resident individual, foreigners, stateless persons and subjects engaged in terrorist activities".

When it comes to individuals, the sanction of asset forfeiture cannot be applied to Ukrainian citizens unless the Ukrainian citizen is engaged in terrorist activities. In this regard, the HACC notes that

"The Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" outlines an exhaustive list of subjects on whom the sanction may be imposed. With respect to individuals, it can only be imposed on non-residents, foreigners, stateless persons, as well as persons engaged in terrorist activities. Only the latter category is mentioned in the law irrespective of the foreign or Ukrainian citizenship"(20).

In the case of Yanukovych, the application of the law to the former President was justified by the fact that he had engaged in terrorist activities(21). This conclusion is based on the Law of Ukraine "On the Prohibition of Propaganda of the Russian Nazi Totalitarian Regime, Armed Aggression of the Russian Federation as a Terrorist State against Ukraine, Symbols of the Military Invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Nazi Totalitarian Regime" (Law 2265-IX). This law recognized the Russian Federation as a terrorist state and supplemented the concept of terrorist activity so that it covers "propaganda of the Russian Nazi totalitarian regime, the armed aggression of the Russian Federation as a terrorist state against Ukraine"(22). Accordingly, the HACC concluded that Yanukovych supported the state policy of the Russian Federation and promoted the ideas of a terrorist state regarding aggression against Ukraine.

However, in the overwhelming majority of cases considered by the HACC, the defendants are citizens of the Russian Federation. Given the imminent threats posed by the war in Ukraine, the legislative approach, according to which sanctions cannot be applied to Ukrainian citizens (except for those who carry out terrorist activities), seems rather controversial.

20. See the cases of Polukhin and Falaleyev.

21. See Chapter 17 of the Yanukovych Case.

Regarding the preceding asset freeze

According to the current Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" (part 3 of Art 6), asset freeze (imposed after May 24, 2022) has to precede the forfeiture.

Along with this, another issue deserves attention in the context of preceding asset freeze. Can (or should) the HACC while considering the claim for forfeiture verify the NSDC"s decision and the Presidential Decree that imposed the asset freeze?

The legal position on the issue was formulated by the Grand Chamber of the Supreme Court in its judgment of 13.01.2021 in case No. 9901/405/19:

"When enacting the NSDC"s decision on such sanctions (asset freeze), the President, as the guarantor of the Constitution of Ukraine, who has been given a representative mandate by the people of Ukraine and who is authorized by the Constitution of Ukraine to enact the NSDC"s decision, must independently assess the existence and sufficiency of the grounds for imposing such a sanction.

Judicial control over such a decision is limited, since, on the one hand, the court cannot reassess the existence and sufficiency of the grounds for imposing such sanctions within the President's discretion (which would mean a violation of the principle of separation of powers), but, on the other hand, the court can verify compliance with the limits of such discretion and the procedure for imposing sanctions".

Based on the Grand Chamber"s position, the HACC verifies whether the President has not exceeded the limits of his discretion and whether the procedure for imposing a sanction has been observed(23). The HACC does not assess whether there were sufficient reasons for asset freeze in the first place. Therefore, if a party to the proceedings (as was the case, for example, in the Deripaska case)(24) points out that a person was groundlessly included in the list of sanctioned persons, the HACC refuses to assess the validity of the asset freeze, apparently implying that such a decision was political and cannot be assessed by the judiciary.

23. See the cases of Yanukovych, Kolbin, Torkunov, Lyabykhov, Paikin and Deripaska.

24. Para 7.13.10.

Regarding evaluative concepts

In order to apply asset forfeiture, the HACC has to establish that the defendant's actions created a significant threat to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine (including through armed aggression or terrorist activity) or substantially contributed (including through financing) to the commission of such actions by others.

While examining the issue the Court must apply the lowered standard of proof, which the HACC not quite accurately calls the "standard of greater persuasiveness" (see above remarks on the standard of proof).

Para 4 part 1 Art 5-1of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions" contains a detailed list of actions that cause a significant damage to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine (ten subclauses in the first clause) and actions that constitute substantial assistance to the latter (twelve subclauses in the second clause) (see Annex 1).

At the same time, the wording of the main formula includes two evaluative concepts, namely "significant damage" and "substantial assistance".

Significant damage and substantial assistance cannot be determined in a general way - they are subject to determination by the court in each particular case. The HACC notes:

"With regard to the requirements... of causing significant damage to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine or the substantial degree of assistance to the commission of such actions (including the form of informational assistance), the court notes that those are evaluative concepts.

Therefore, the specific circumstances of the case should be weighed for the defendant's actions to be ascertained under those criteria(25)".

For example, publishing a post on a social network in support of Russian aggression may constitute substantial assistance in some cases, but not in others. If such a post is made by an ordinary citizen, it is unlikely to have sufficient effect. Instead, if the post is made by the rector of a university(26) with many thousands of students on the official page of the institution as part of an ongoing campaign to support aggression, it may well be recognized as substantial assistance.

Substantiality of assistance means that the defendant's causal contribution to the "joint venture" of the aggressive war against Ukraine is palpable, noticeable, and significant in the context of the total efforts of all those involved in the crime. Table 1 provides an idea of what kind of assistance the HACC recognizes as substantial, i.e. sufficient to entail forfeiture.ʼ

25. See Polukhin case.

Establishing the ownership of assets

Establishing the ownership of the assets is probably the most intricate part of the proceedings in this category of cases. This is due to the fact that not only the assets owned by the defendant directly (i.e., assets in respect of which the defendant has a title of ownership) are subject to forfeiture, but also the assets that the defendant effectively controls without being the formal owner thereof (the latter include assets controlled through front companies, dependent companies, affiliates or a chain of related legal entities).

The latter category of assets is described in the Law as follows: assets in respect of which "the defendant may directly or indirectly (through other individuals or legal entities) exert powers effectively identical to the power of disposition" (11 part 1 Art 4 of the Law of Ukraine On Sanctions"). Establishing the said effective control over the assets is a challenge. It is associated with a complex ownership structures that sanctioned persons can use to conceal the fact that they are the ultimate beneficiaries of the relevant legal entity(27).

The HACC explains the formula used in the Law as

"the ability of a person to decide on the legal and actual fate of the assets (including through alienation to other persons); to make direct or indirect management and administrative decisions in relation to them; to determine priority areas of development; to identify counterparties; to use profits and/or receive income from the assets. Such an ability may stem from a person's ownership of corporate rights, provisions of the law and/or special relationship with other persons. Moreover, in the context of corporate rights, the ability to exert powers identical to the power of disposition is inextricably linked to the determination of the ultimate (formal or informal) beneficial owner of legal entities"(28).

Assets over which a person exercises indirect control are usually associated with a complex ownership structure (when a sanctioned person controls a legal entity that controls another legal entity that controls yet another, and so on - up to the last legal entity, which is the formal owner of the property in question) or with the use of a straw man (i.e., individuals who are only nominal owners of an asset, while all decisions on the disposal of such an asset are made by the sanctioned person).

In determining whether the defendant exert powers effectively identical to the power of disposition the HACC resorts to the following concepts:

- ultimate beneficial owner(29);

- direct and indirect decisive influence(30);

- significant participation and indirect significant participation(31);

- control(32);

- related parties(33);

- chain of ownership of corporate rights of a legal entity(34);

- affiliated persons(35);

- ownership structure of the legal entity(36).

The ownership structure often includes companies registered under foreign law. This can potentially create an opportunity to circumvent sanctions, provided that at least one of the companies in the chain is located in a jurisdiction that has not imposed sanctions on the defendant. For example, the defendant is the founder of company A, which is registered in country X. Company A, in turn, controls company B, which controls company C, which is located in Ukraine and whose assets are frozen.

However, if no sanctions have been imposed against the defendant in country X, then even after the freeze of the assets in Ukraine, in country X the defendant retains the right to dispose of his/her share in company A. Accordingly, defendant may sell his share in company A to another person even while his/her assets are frozen in Ukraine, and thus, company C, located in Ukraine, will formally lose connection to the defendant by the time of the forfeiture proceedings.

A similar situation arose in the Shelkov case concerning Demurinsky Mining and Processing Plant LLC(37). 100 percent of it"s shares belong to Limpiesa Limited, a company registered in Cyprus. On February 20, 2022, after the freeze of Shelkov's assets in Ukraine, a 75 percent stake in Limpieza Limited was sold by the Shelkov-controlled Avisma Corporation to the Cyprus-based Bolatico Limited for EUR 3,750 (while in 2019, a 25 percent stake was sold for USD 3 million).

The Ministry of Justice insisted that the transaction was fictitious. However, the HACC disagreed, noting that this fact was not sufficiently proven and, moreover, there was evidence that the reason for the change of ownership could be a real corporate conflict within the company. Judge Khamzin T.R. disagreed with the majority and expressed a separate opinion on this matter. Subsequently, the HACC Appeals Chamber concluded that the agreement on the alienation of shares in Limpieza Limited was null and void and reversed the HACC judgment in the relevant part, supplementing the list of confiscated property with assets controlled through the company.

The difficulty of establishing the ownership of assets is also illustrated by the Deripaska case, especially in the part concerning Khust Quarry and Zhezhelevsky Quarry(38). In order to circumvent the sanctions, the shares in the quarries were sold during the assets freeze. However, the HACC held that the defendant nevertheless retained control over these assets. The court, in particular, took into account the fact that the nominal owner did not have sufficient capital to purchase the assets (the purchase price was more than three annual salaries of the buyer), no valuation and/or audit of these assets was conducted before the sale, and that the subsequent changes in the supervisory board of the company that became the new owner of the quarries indicate that the defendant retained effective control over the assets.

In the case of Rotenberg et al. the HACC noted that the tools developed to combat money laundering may be helpful in establishing indirect control over assets (para. 81):

"This category of criminal offenses involving the concealment of property and its true origin under the guise of legitimate business activities by companies registered in foreign jurisdictions with a high level of confidentiality and relaxed currency/tax legislation (those that do not disclose information about owners (founders, shareholders), ultimate beneficiaries, business reports, etc.) is very much akin to circumventing the sanctions through corporate structures."

In particular, the Court noted the appropriateness of using the ‘Forty Recommendations’ of the of the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) and the International Standards against Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction.

In this context, from a civil law perspective, the question arises as to the validity of the agreements aimed at circumventing the sanctions. The situation is further complicated by the fact that under private international law, disputes regarding the invalidation of such agreements may not be subject to the jurisdiction of Ukrainian courts (given that the parties to such agreements are companies registered abroad). However, in this regard, it should be emphasized that, firstly, a lower standard of proof is applicable in this category of cases, and secondly, the subject of proof in the case is not the formal validity of a particular agreement, but the question of whether the defendant, despite the relevant share alienation agreement, retained the real ability to control and dispose of the asset. And if the court, based on the analysis of all the evidence in the aggregate, concludes that it is most likely that the defendant has retained such a power, the asset may be subject to forfeiture without the need to formally invalidate the agreement.

28. Deripaska case, para. 7.14.3.

29. Para 30 part 1 Art 1, the Law "On Prevention and Counteraction to Legalisation (Laundering) of Criminal Proceeds, Terrorist Financing and Financing of Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction" (Law No. 361-IX)

30. Ibid. In the case of Rotenberg et al. the HACC generally equated ‘indirect decisive influence’ with the concept of ‘actions equivalent to the exercise of the right of disposal’, which is used in paragraph 1-1 of Article 4 of the Law of Ukraine ‘On Sanctions’ (para. 92)

31. Para 30 part 1 Art 1 Law No. 361-IX; Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine "On Banks and Banking Activities".

32. Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine "On Banks and Banking Activities".

33. Subparagraph 14.1.159 of the Tax Code.

34. Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine "On Banks and Banking Activities".

35. Clause 1 of Part 1 of Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine "On Joint Stock Companies".

36. Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine "On Banks and Banking Activities".

37. Shelkov case, para. 5.8.3.

38. Deripaska case, para 7.14.16. and following.

Protection of the rights of third parties

The imposition of a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture may potentially create risks for the rights of third parties. The simplest scenario is when the defendant's property is encumbered by the rights of third parties. For example, real estate owned by the defendant is pledged to a third party.

Pursuant to para 3 part 1 of Art 5-1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions":

"Seizure of assets, imposition of a moratorium or any other encumbrances (prohibition to dispose of or use them), as well as pledging of such assets, shall not prevent the forfeiture as a sanction provided for in clause 11 part 1 Art 4 of this Law."

It follows from this article that the asset being pledged to a third party does not prevent the forfeiture. But does this mean that the pledge right is terminated as a result of forfeiture?

A similar problem arose in the case of Falaleyev, which concerned the forfeiture of an apartment owned by the defendant and mortgaged by a bank. The HACC concluded that the forfeiture of the apartment does not terminate the rights of the mortgagee:

"The court believes that the forfeiture of the defendant's assets in the form of property rights in the apartment, even taking into account the existing encumbrances (mortgage agreement with the third party – Ukrgasbank) is a proportionate interference with the right to property, which will not automatically deprive the third party of its rights arising from the mortgage agreement. When a court decides to impose a sanction on a defendant, this decision does not remove the existing encumbrances third parties may have over the asset".

In general, this conclusion is in line with the civil law principle that the pledge right persists upon change of ownership of the pledged asset(39). Yet in practice, the pledgee may face difficulties due to the moratorium(40) on the forced sale of state-owned enterprises" property.

The risks to third party rights are even more acute in the context of corporate ownership chains and complex ownership structures. Suppose that the defendant owns 60 percent of the shares in company A, which in turn owns 100 percent of the shares in company B. 60 percent in company A is sufficient for the court to find that the defendant also exercises indirect control over company B as well. Accordingly, the corporate rights in company B in the amount of 100 percent may be forfeited, since with regard to those the defendant exerts powers identical to the power of disposition. However, if forfeiture is effected, third parties who own the remaining 40 percent of shares in Company A will suffer losses, as it means that their company has lost a valuable asset.

This issue remains unresolved at the legislative level. It may be advisable to introduce mechanisms to compensate such third parties. In particular, it may be necessary to establish the obligation of the state to buy out the third party's share if, after the defendant's share has been collected for the state's benefit, the third party (shareholder) makes such a request. However, one should not lose sight of the fact that such persons may also be indirectly related to the sanctioned person, and this is subject to court determination. In this context, the burden of proof of good faith may be saddled on the persons alleging violation of their rights by the forfeiture

Conclusion

The above observations and recommendations are aimed at ensuring compliance with the rule of law when applying the sanction in the form of asset forfeiture. The measure undoubtedly constitutes an interference with the sanctioned person's right to peaceful enjoyment of his or her property. It is therefore an imperative that such interference be compatible with international human rights standards. According to the ECtHR case law, interference with the right to property is compatible with the requirements of Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the ECHR (Protection of Property), provided that (a) such interference is lawful; (b) it is aimed at achieving a legitimate aim and (c) it is proportionate to that aim(40).

The HACC is conscientious about the compliance with the said requirements; and in every judgment it refers to the relevant case law of the ECtHR. It is noteworthy, among other things, that the HACC checks whether forfeiture would be an excessive burden for each individual defendant. In particular, the HACC often notes that the defendants own property outside Ukraine not covered by confiscation measures and therefore defendants would not be deprived of their critical livelihoods.

At the same time, it should be noted that when considering the relevant category of cases, the rules of international investment law should also be taken into account. In particular, the Agreement between the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine and the Government of the Russian Federation on the Encouragement and Mutual Protection of Investments (ratified by Law No. 1302-XIV of December 15, 1999) has not yet been formally disavowed.

However, the provisions of the Agreement should be interpreted in the context of the UN International Law Commission's Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts. Article 25 of the Articles refers to the state of necessity, which may justify a state's actions that would otherwise be considered a violation of its international obligations. The state of necessity may be invoked if the State"s act (a) is the only way for the State to safeguard an essential interest against a grave and imminent peril; and (b) does not seriously impair an essential interest of the State or States towards which the obligation exists, or of the international community as a whole.

To avoid any uncertainty, however, it would be advisable to disavow the agreement with the government of the aggressor state on mutual protection of investments

Annex 1

Grounds for imposing sanction in the form of asset forfeiture (para 4 part 1 Article 5-1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions")

The grounds for imposing a sanction in the form of asset forfeiture (para 4 part 1 Article 5-1 of the Law of Ukraine "On Sanctions") are as follows:

1. causing significant damage to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine, in particular, but not exclusively, by:

- а) making a decision on armed aggression against Ukraine;

- б) participating in the decision-making process (by supporting such a decision with own vote) regarding the armed aggression against Ukraine, if such a decision was made collectively or by several bodies of the aggressor state in cooperation;

- в) participation in the preparation, submission and approval of proposals for making a decision on armed aggression against Ukraine;

- г) participation in state financing and logistical support of activities related to the decision to launch armed aggression against Ukraine;