>

Analytics>

Overview of the current regulation of liability for sanctions evasion: state of play and prospectsOverview of the current regulation of liability for sanctions evasion: state of play and prospects

The research paper describes the state of play and main trends in Europe and the United States with regard to evasion of sanctions imposed as a result of Russian aggression and criminalisation of such activities. It analyses Ukrainian draft law on sanctions evasion. Particular attention is paid to the possibility of transferring the funds collected through prosecution for sanctions evasion to compensate for the damage caused by the Russian aggression against Ukraine.

This publication has been made possible through the generous support of the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor Affairs of the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

Publisher: think tank “Institute of Legislative Ideas”. All rights reserved.

Authors: Tetiana Khutor, Andrii Klymosyuk, Taras Riabchenko, Bohdan Karnaukh

Section I

Context. Russia, sanctions and sanction evasion

Examples of the use of restrictive measures in one form or another have a long history and date back to the times of ancient Athens, where trade sanctions were imposed on merchants of the city of Megara (432 BC). In their modern form, sanctions (in international law, “retorsions”) became widely used in the XX century as a method of exerting leverage by a state, group of states or international organisations on another state or its citizens to change their behaviour and cease wrongful actions. The most intense sanctions policy was implemented by the United States, in particular against Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution; the other example is the UN, which imposed restrictions on countries that violated international law (Iraq, Haiti, Yugoslavia, etc.) at the end of the century.

Sanctions may include various measures, such as trade embargoes, financial bans, flight bans, diplomatic restrictions, as well as individual restrictions applied to certain individuals or legal entities (travel bans, freezing of funds, etc.). The purpose of sanctions may vary from case to case and depend on the context and circumstances in which they are imposed.

For example, the key objectives of EU sanctions include(1):

- safeguarding EU's values, fundamental interests, and security;

- preserving peace;

- consolidating and supporting democracy, the rule of law, human rights and the principles of international law;

- preventing conflicts and strengthening international security.

Despite the use of rather broad concepts, such as "preserving peace", the world has not yet invented universal restrictions that would be a panacea and instantly stop perpetrators. Therefore, the instrument of sanctions is constantly changing, adapting to new demands and challenges, in particular, to new risks to global security.

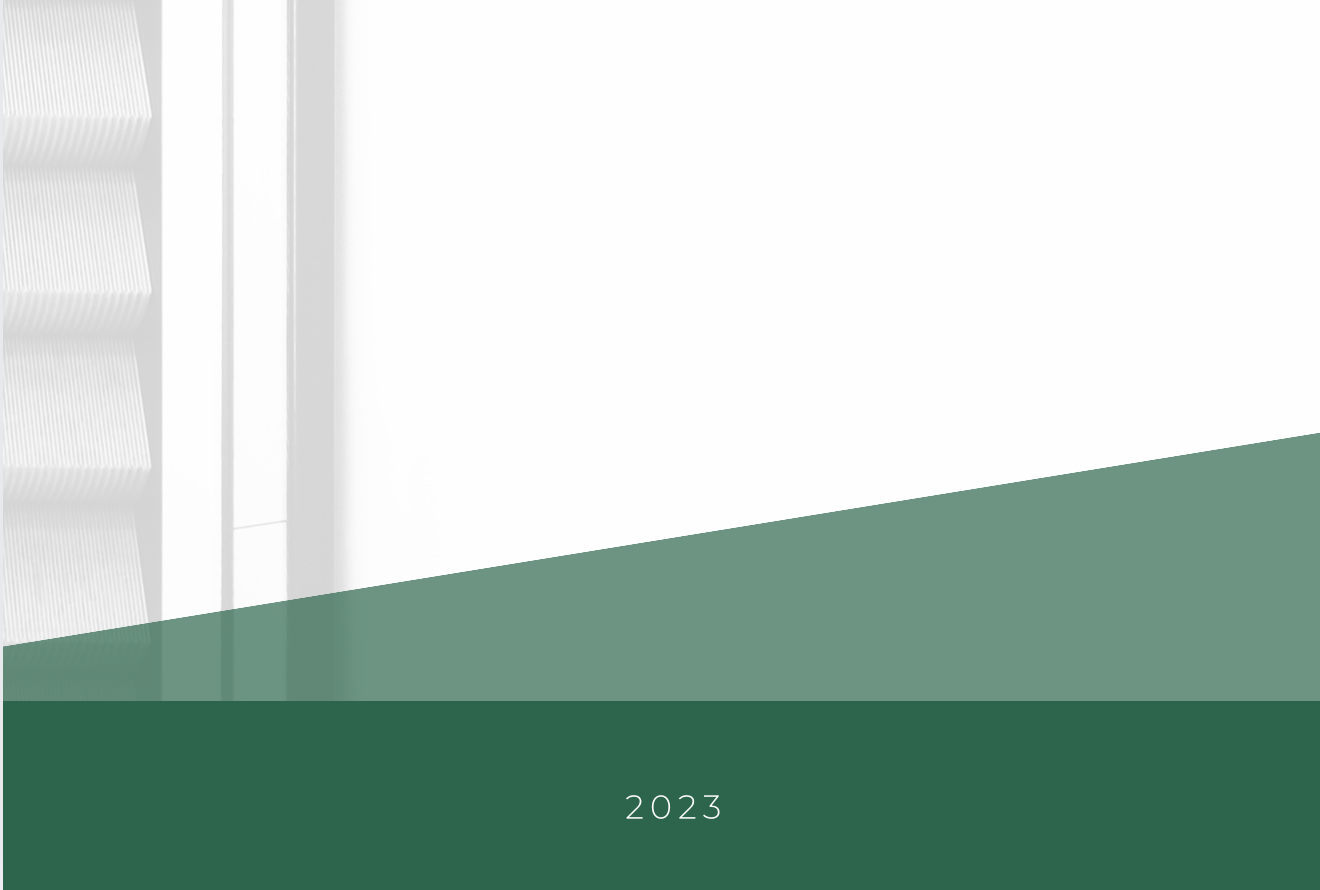

A new wave of sanctions evolution and changed sanctions policies of states is associated with Russia's gross violations of international law against Ukraine. In 2014, 41 countries imposed sanctions on Russia in connection with the annexation of Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

After that, until 2022, the sanctions pressure of the US, EU, other states and international organisations on Russia and Putin's henchmen only increased. However, as practice has shown, this failed to prevent the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the outbreak of the largest military conflict in Europe since the Second World War.

Source: castellum.a

However, as the number of restrictions imposed multiplies, so do the number of cases where such restrictions are circumvented, either by directly violating prohibitions or by finding loopholes in legal instruments and regulations. Unfortunately, when it comes to the possibility of making excessive profits, individuals and companies prefer significant financial gain over respect for human rights and the international legal order.

Even before the full-scale invasion, in 2019, MEPs pointed out(2) that sanctions violations had become a systematic problem, and after 2022, the cost of this "problem" has risen even higher.

A telling fact is that about thirty foreign microchips, including those from the countries that imposed the sanctions, were found in Russian missiles manufactured after the technology embargo was imposed(3). This became possible as a result of sanctions circumvention, which not only figuratively but also literally lead to the casualties in Ukraine.

The number of reported cases of evasion is staggering, but one should realise that it is only the tip of the iceberg.

For example, in Estonia(4) alone, which is relatively small in terms of territory, 1,500 cases of sanctions violations were detected, and the Swiss(5) authorities are already investigating 100 cases of possible sanctions violations against Russia, with another 300 cases pending.

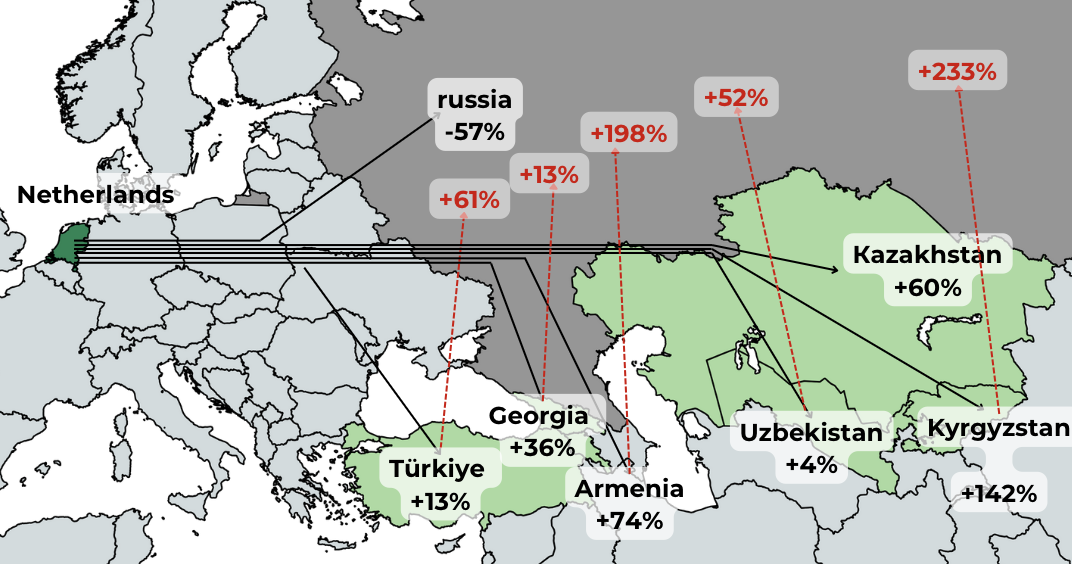

The global state of sanctions evasion is vividly evidenced by the dynamics of exports of goods from certain EU countries to third countries and their subsequent sale to Russia. For example, exports of goods from the UK to Kyrgyzstan have increased by more than 4000% over the past year(6). The situation is similar with exports of goods from the Netherlands to Russia's friendly countries.

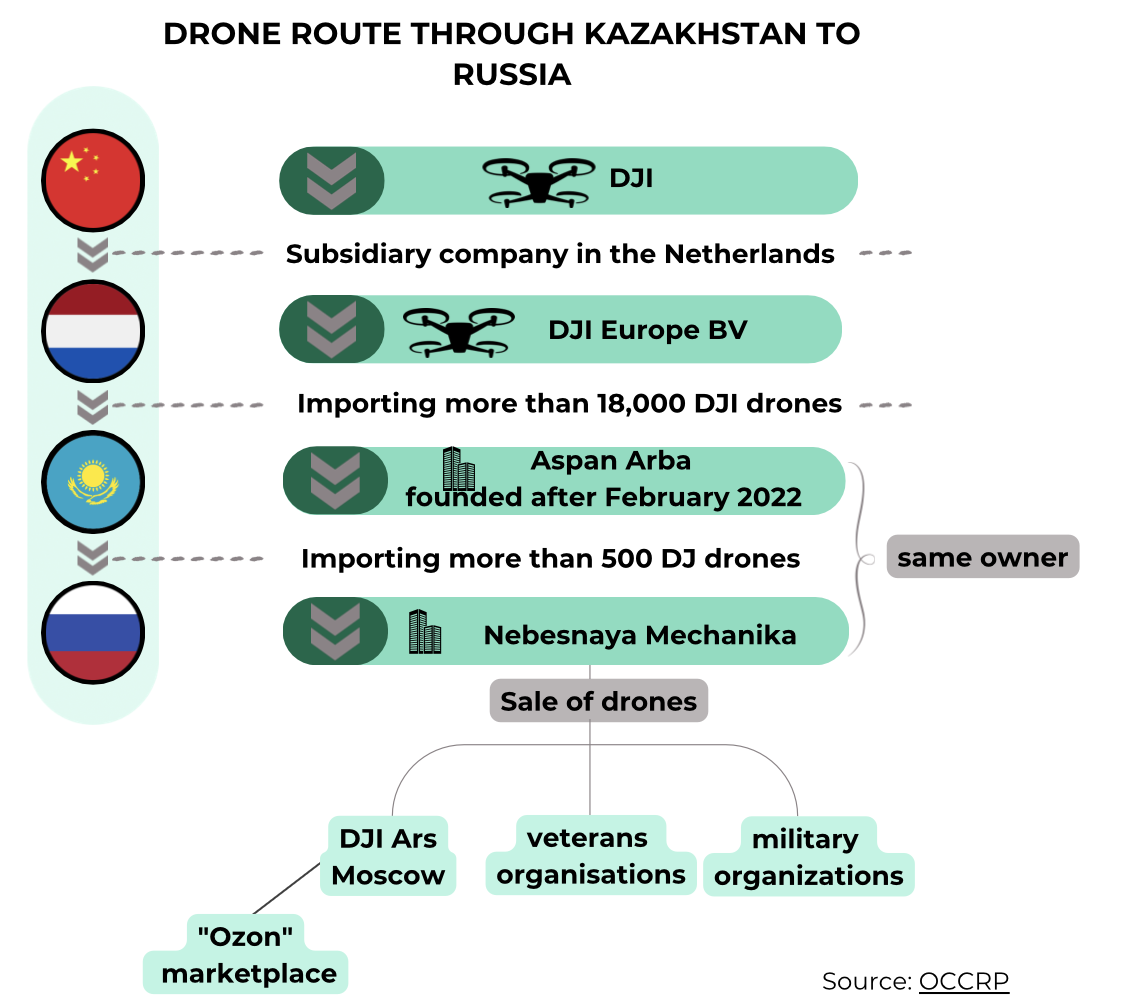

According to journalists investigations(7), numerous loopholes and corruption schemes still allow Russia to obtain the necessary technologies for warfare. For example, through the creation of various subsidiaries in China, Kazakhstan and the EU, many sanctioned goods, including military or dual-use goods, were imported into Russia.

In this regard, world leaders are currently urging to focus on strengthening the enforcement of the already imposed restrictions.

In particular, the European Union's chief diplomat, Joseph Borrell, said that the EU has almost exhausted sanctions against Russia and will now concentrate on the issue of sanctions evasion. This political statement was reflected in the 11th package(8) of EU sanctions.

At the same time, it is important to understand that ensuring the effectiveness of sanctions does not depend solely on eliminating loopholes and taking measures to strengthen control.

In an environment where there are already multiple ways to circumvent sanctions and new and more sophisticated ways to evade them are emerging every day, it is important to prevent such actions. It is all about penalties for sanctions evasion as a relatively new but necessary measure that can significantly contribute to the effectiveness of sanctions and compliance with sanctions “discipline”.

The threat of an inevitable and sufficiently severe punishment will be able to stop potential violators when the possible consequences outweigh the possible financial benefits of circumventing sanctions.

In addition, since the reason for the imposition of these sanctions is in fact Russia's war against Ukraine, it would be logical for the proceeds of crime or assets seized in the course of the investigation to be directed to Ukraine as the injured party.

Therefore, it is important not only to establish appropriate penalties and bring the perpetrators to justice, but also to introduce special legal mechanisms by partner countries that would allow the transfer of the funds received to compensate for the damage caused.

Thus, prosecution for sanctions evasion would not only have a deterrent effect, but could also become an additional source of replenishment of the Compensation Fund, as one of the elements of the global Compensation Mechanism currently being implemented by Ukraine and its partners.(9)

In this paper, we will examine the current legal framework for sanctions evasion liability in the partner countries (EU, UK, USA) and the dynamics of legislative changes in the area. The Ukrainian case will be discussed separately and the proposed model of criminalisation of sanction evasion in Ukraine will be analysed.

Section II

Liability for sanctions evasion in Europe and the United States. Search for common approaches and first successful cases

The countries of the European continent had close economic ties with Russia. It is also well known that Russian oligarchs and other supporters of the aggressor (politicians, propagandists, etc.) keep most of their wealth in Europe (buying real estate, investing or keeping it in bank accounts).

However, despite the relative unity of the political position of European countries on the imposition of sanctions, there is no single approach to liability for circumventing them.

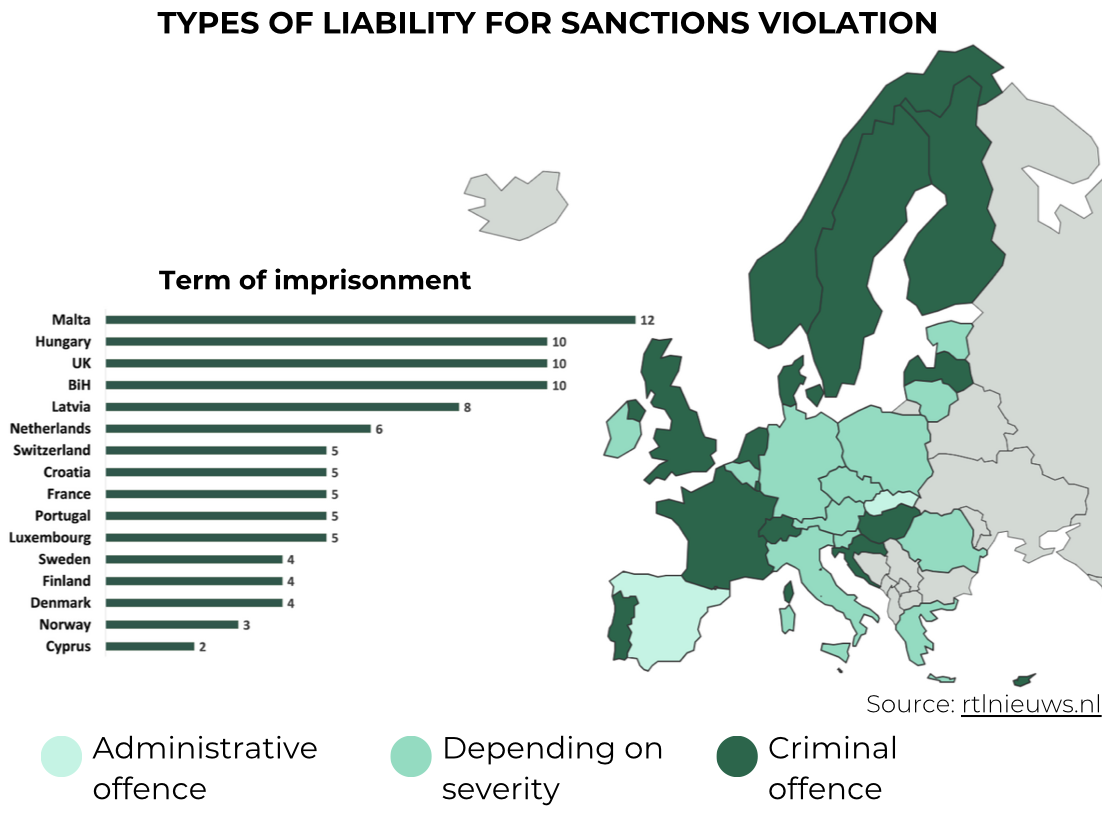

For example, a large number of EU countries classify violation of sanctions as a criminal offence (Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden), while in Slovakia and Spain(10) it is considered an administrative offence.

At the same time, in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovenia, such violations may be classified as either criminal or administrative offences, depending on their severity.

As regards non-EU European countries, in Norway, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, for example, violation of sanctions is a criminal offence.

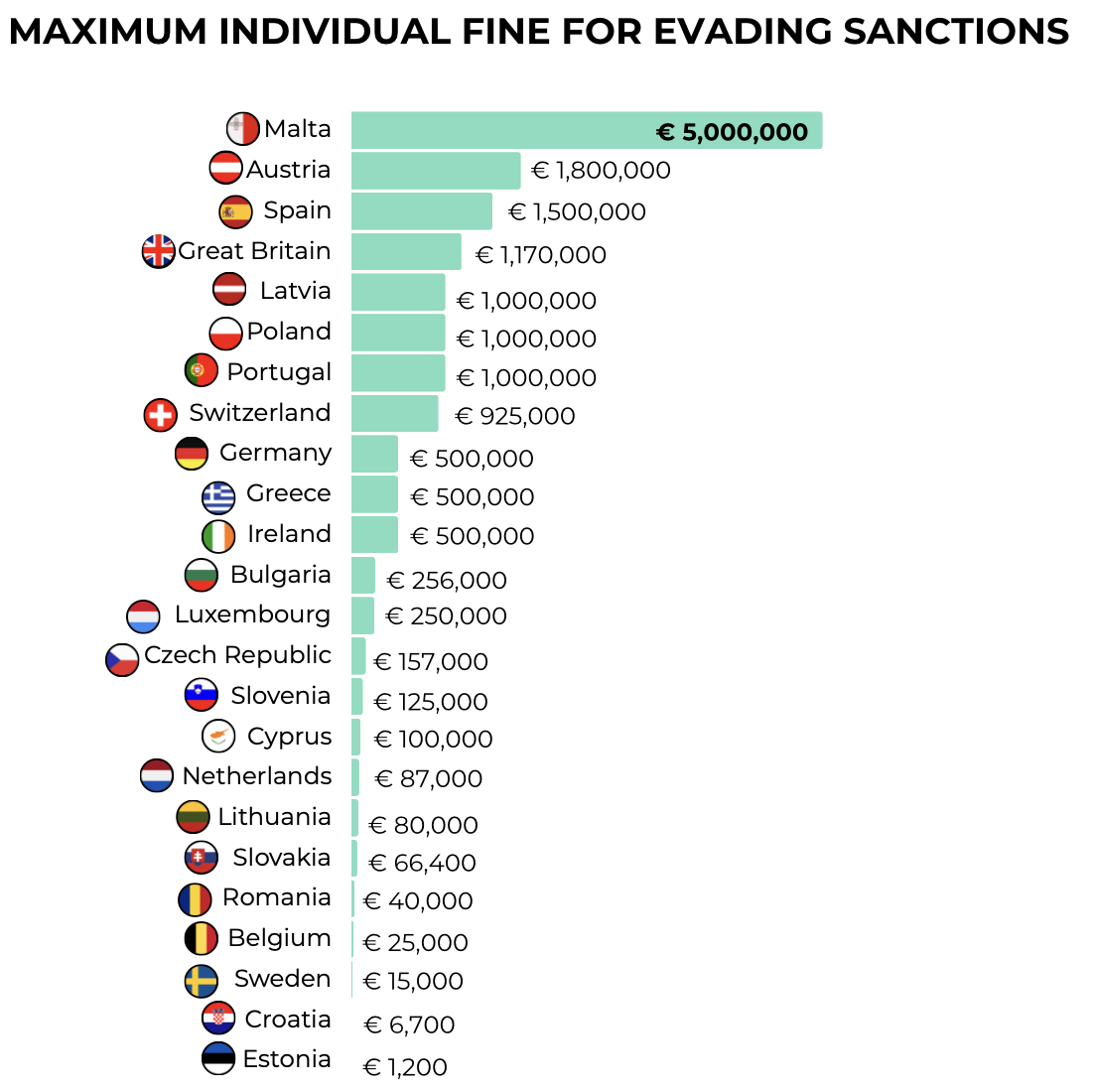

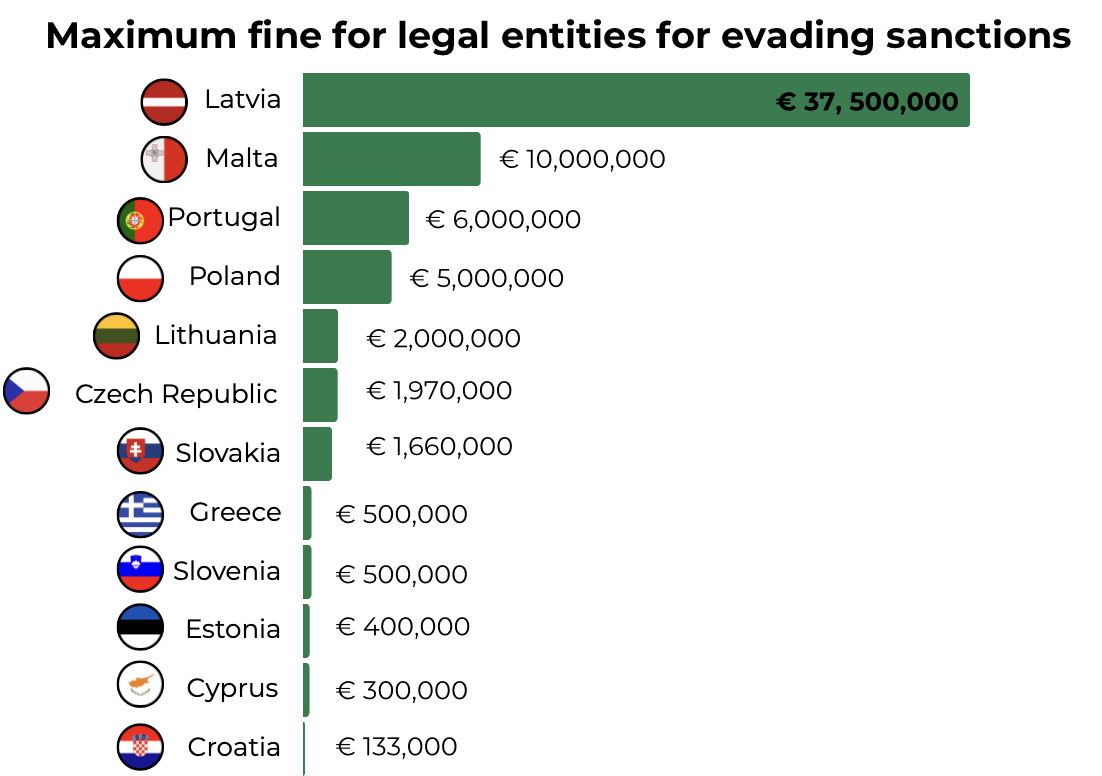

There are even greater differences between EU countries in terms of the penalties for sanctions violations.

In Greece, the maximum prison sentence is 6 months, while in Malta and Italy it is 12 years. In 9 EU countries, the prevailing penalty is 5 years in prison. Interestingly, despite the existence of criminal liability for sanctions violations in Romania, there is no imprisonment for such a crime at all.

In non-EU countries, the situation is similar: the maximum prison term for circumventing sanctions in the UK and Bosnia and Herzegovina is 10 years, in Switzerland - 5 years, and in Norway - 3 years.

The situation is similar with the maximum fines for sanctions evasion.

For individuals, they range from €1,200 (in Estonia) to €5 million (in Malta), and for legal entities - from €133,000 (in Croatia) to €37.5 million (in Latvia). In total, Malta is the EU country with the most severe system of penalties for violating sanctions.

As for non-EU countries, in the UK, the fine for individuals is EUR 1.170 million, in Switzerland - EUR 925 million, and in Norway, the maximum fine is not defined.

Such a lack of uniformity in the type and extent of liability contributes to the fact that potential violators may choose the most “safe” jurisdictions to circumvent sanctions, despite the fact that such violations are of a cross-border nature.

In addition, it significantly reduces the effectiveness of coordination and cooperation between authorised bodies within different states.

With regard to the possibility of confiscation of the instrumentalities of crime and the proceeds of crime, the issue is regulated at the EU level by Directive 2014/42/EU(11). It provides for the possibility of seizure and confiscation for a number of terrorist, corruption and economic crimes. However, there is currently no direct reference in the Directive to the sanctions evasion, so Member States address this issue in accordance with their national legislation.

Source: eurojust.europa.eu

At the same time, it should be noted that the criminal law of most EU countries provide for confiscation of the instrumentalities of crime and proceeds of crime in one form or another for all crimes(12).

Of course, where sanctions evasion is not criminalised, confiscation is not possible. It also has a negative impact on law enforcement practice, given the cross-border nature of sanctions evasion.

In view of the above situation in the EU, the European Commission decided to put an end to impunity for these acts and began to implement a two-stage introduction of criminal liability at the Union level. The first stage was the decision(13) of the European Commission in May 2022 to address the Council of the EU to adopt a decision to designate the violation of EU restrictive measures as an EU crime.

Source: eurojust.europa.eu

Accordingly, by the Decision(14) of the Council of the European Union of 28 November 2022, the violation of the EU restrictive measures (sanctions) became a crime under EU law. The second step was the Commission's proposal(15) for a Directive on the definition of criminal offences and penalties for the violation of Union restrictive measures.

The introduction of a unified approach, which will be reflected in the Directive and implemented in the legislation of the EU Member States, will facilitate the effective investigation and punishment of such violations in all Member States.

The aims of the proposed Directive are as follows:

To define criminal offences related to the violation of EU restrictive measures. The definition shall cover

a) making funds or economic resources available to a designated person, entity or body in violation of a prohibition by a Union restrictive measure;

b) failure to ensure, without unreasonable delay, the freezing of funds or economic resources belonging to a person or legal entity subject to restrictive measures;

c) carrying out financial activities that are prohibited or restricted;

d) conducting prohibited or restricted trade.

- The offences would also cover the circumvention of EU sanctions, for example, by concealing the fact that a person subject to restrictive measures is the owner or beneficiary of certain funds or by failing to provide information about frozen funds or l funds that have not been frozen by the relevant administrative authorities and are owned, held or controlled by a designated person.

- To establish the types of penalties for individuals. These penalties are applicable to all the offences above. The most severe penalty is imprisonment for up to 5 years (if the value of the assets was EUR 100,000 or more). Member States should establish effective, proportionate and dissuasive penalties.

- To establish minimum penalties for legal entities. These include: fines of up to 5% of annual turnover, revocation of licences, deprivation of the right to engage in business activities, and liquidation through court proceedings.

- It also provides for guarantees against self-incrimination, as well as guarantees for lawyers in terms of providing legal assistance, unless it is established that such assistance is provided with the aim of violating EU restrictive measures.

The next step is to discuss the proposed Directive in the European Parliament and Council under the usual procedure of joint legislative action. Under this procedure, both institutions will have the opportunity to propose amendments, and both will have to approve the proposed Directive before it can enter into force.

Important steps to combat sanctions evasion in the EU include not only the harmonisation of legislation, but also the optimisation of the activities of the bodies charged with the responsibility to implement it.

In July 2022, Justice Commissioner Reynders asked the European Public Prosecutor's Office whether it would be technically possible to extend its competence to include circumvention of EU restrictive measures. The answer was: "yes, it is possible, and the European Public Prosecutor's Office should be better placed to do so than the known alternatives". At the Justice Council in October 2022 and in subsequent discussions, this idea was received with general favour. In a joint statement, the French and German Justice Ministers called for the expansion of the European Public Prosecutor's Office's powers to investigate and prosecute sanctions circumvention. The European Parliament supported this idea in its annual report on the implementation of the Common Foreign and Security Policy for 2022(17).

The report notes, in particular, that the European Parliament:

“strongly supports the proposal for a directive criminalising the violation of Union restrictive measures and calls on the EUropean Public Prosecutor’s Office to be tasked with ensuring the consistent and uniform investigation and prosecution of such crimes throughout the EU”.

Thus, the dynamics of legislative processes in the EU indicate that there is a political will to fight against sanctions evasion in a decisive and robust manner. However, given the rather complicated procedure and the need to amend the legislation of all EU member states, these steps will be introduced and implemented, at best, in the next few years.

The UK, as the favourite country of Russian oligarchs, is also ready to introduce changes aimed at strengthening the fight against sanctions evasion.

In general, sanctions evasion and circumvention are key enforcement priorities for the UK sanctions authorities in 2023.

In June 2022, the UK adopted amendments to the Police and Crime Act 2017(19), which allow civil fines for sanctions violations to be imposed on a "strict liability regime" (even in the absence of proof of guilt or criminal intent).

In addition, the fight against sanctions evasion may soon be strengthened by an amendment(20) to the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill, which was submitted on 27 April 2023 by Lord Alton of Liverpool, a member of the UK House of Lords.

Lord Alton’s amendment suggests the following:

1. The designated persons are required to report to the Treasury or another competent authority, within three months after such regulations are made or within three months from the date of designation, whichever is the latest, the funds or economic resources that—(i) are currently held, owned or controlled by them within the United Kingdom, and(ii) were held, owned or controlled by them within the United Kingdom six months prior to the date of designation, and(b) to cooperate with the Treasury or other competent authority in any verification of such information.

2. Failure to comply with this obligation should be treated as sanctions circumvention.

3. A person who fails to comply with the obligation to report his or her assets and is therefore found guilty of sanctions evasion should be deemed to have benefited from the value of any assets concealed as a result of such criminal behaviour. On this basis, she should be subject to confiscation under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002(21) (Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 , articles 5, 6, 92 and 156). Assets concealed as a result of a failure to comply with the reporting requirement constitute property that may be subject to confiscation for the purposes of section 5 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

The Bill with this amendment is currently in the final stages of consideration. Following the third reading in the House of Lords on 4 July, the House of Commons is due to pass the amendments proposed by the House of Lords on 4 September. These amendments will significantly strengthen the sanctions discipline and will disclose previously unknown and unfrozen assets at the risk of confiscation. Those who evaded their duty and concealed their assets will lose them.

In summary, there is a positive trend towards toughening legislation to curb sanctions circumvention.

The unification of criminal provisions across the EU will close jurisdictional opportunities for violators and become an effective and strict tool to combat such crimes. Amendments to the British law will effectively combat kleptocracy under sanctions and the concealment of wealth.

The steps towards the introduction of self-declaration rules for designated persons in the EU and the UK with the possibility of confiscation for violation of this rule is a positive development.

Meanwhile, the operational costs of effective investigation and administration of these processes, given the cross-border nature of such crimes, can be significant. Therefore, part of these costs may be covered by the collected assets, but it would be fair to use the bulk of the funds (80+%) to compensate for the damage caused. The development of relevant legislative changes that would allow the transfer of such assets is an equally important task, and therefore such steps should be actively advocated among experts and decision-makers in European partner countries.

In the United States, the legal basis for the imposition of sanctions is provided by a special law - the International Emergency Economic Powers Act or IEEPA(22) - which grants the President special economic powers to respond to an "unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States".

In order for the special powers regime to be activated, the President must declare a national emergency in relation to the threat.

In the case of the events of 2014 in Ukraine, such a national emergency was declared by the then President Barack Obama in his Executive Order No. 13660(23) of 6 March 2014, and since then it has been renewed by subsequent Executive Orders (No. 13661, No. 13662, etc.) and continues to this day.

The same Executive Order defined broad categories of persons whose US assets are subject to blocking. Among them, in particular, are the persons “responsible for or complicit in, or that have engaged in, directly or indirectly, any of the following: (A) actions or policies that undermine democratic processes or institutions in Ukraine; (B) actions or policies that threaten the peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity of Ukraine”.

With respect to a person whose assets are blocked, the EO prohibits, first, any disposition of any interest in property in the United States, second, the receipt of funds, goods or services from US persons, and third, the receipt of funds, goods or services by US persons from such person.

While the Presidential Executive Order outlines broad categories of persons whose assets are subject to blocking, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) compiles lists with individual names.

Violation of sanctions imposed under IEEPA is criminalised in the United States. Pursuant to 50 U.S.C. 1705(c)(24) , it shall be unlawful for a person to violate, attempt to violate, conspire to violate, or cause a violation of any license, order, regulation, or prohibition issued under the IEEPA. The penalty is imprisonment for up to 20 years.

The initiation of criminal proceedings against a person on the relevant charge provides for the possibility of confiscation of assets that qualify as proceeds of crime. This includes the so-called “civil forfeiture”(25), i.e. confiscation without a guilty verdict. Civil forfeiture is a forfeiture in rem, directed against property (and not against the person who committed the crime) that was obtained from or used to commit the crime. Unlike criminal forfeiture, there is no need for a conviction, although the state is still obliged to prove in court that the property was related to the criminal activity.

This type of forfeiture is provided for in 18 U.S.C. 981(a)(1)(C)(26), which states that any property, real or personal, that constitutes the proceeds of “specified unlawful activity” or a conspiracy to engage in such activity is subject to forfeiture in the United States.

In December 2022, the United States passed a law(27) allowing the transfer to Ukraine of funds received from the sale of forfeited assets of sanctioned persons. According to this law, the Attorney General may transfer to the Secretary of State the funds received from the forfeited property for use by the Secretary of State to assist Ukraine in compensating for the damage caused by Russian aggression.

Such a transfer is considered foreign aid under the Foreign Assistance Act 1961, including for the purposes of the administrative powers and reporting requirements contained in that Act.

The first case to test the mechanism of civil forfeiture (as part of criminal proceedings on charges of sanctions violation) with the subsequent transfer of funds to the needs of Ukraine was the case of Konstantin Malofeyev(28).

In April 2022, a criminal case was initiated in the United States against Russian oligarch, media magnate, founder of the Orthodox TV channel Tsargrad TV, Konstantin Malofeyev. He is accused of violating sanctions imposed by the United States back in 2014, during the first stage of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

The indictment states(29) that Malofeyev, contrary to the established prohibitions, hired an American citizen, Jack Hanick, to work for Malofeyev's television companies in Russia and Greece, as well as to participate in the acquisition of a television company in Bulgaria. In addition, Malofeev attempted to retroactively re-register his USD 10 million investment to a shell company in order to circumvent the sanctions imposed on him. Simultaneously with the indictment, the prosecutor's office requested the forfeiture of Malofeyev's assets. On 2 February 2023, the court granted the prosecution's motion to forfeit Malofeev's US assets totalling USD 5.4 million.

District Judge Paul Gardephe (Manhattan Federal Court) allowed(30) the prosecution to forfeit Malofeyev's funds totalling $5.4 million. Malofeyev did not appeal against the forfeiture decision. The US Attorney General Merrick Garland said(31) that the funds would be transferred to help Ukraine.

Compliance with the sanctions regime in the US is monitored, in particular, by the following agencies: The U.S. Department of the Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS).

FinCEN and BIS have issued an Alert(32) urging financial institutions to be vigilant of attempts by individuals and entities to circumvent export controls imposed in response to the Russian Federation's invasion of Ukraine. This Joint Alert provides financial institutions with an with an overview of BIS’s current export restrictions; a list of commodities of concern for possible export control evasion; and select transactional and behavioral red flags to assist financial institutions in identifying suspicious transactions relating to possible export control evasion.

In March 2022, the interagency task force KleptoCapture was established(33). Its task is to ensure compliance with the wide-ranging sanctions, export restrictions and economic countermeasures imposed by the United States, together with its allies and partners, in response to Russia's unprovoked military invasion of Ukraine. The efforts of this task force helped the United States to initiate a number of cases of sanctions violations, which ultimately resulted in fines and confiscation of property.

For example, in February 2023, a lawsuit was filed

to confiscate six luxury properties owned by Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg with a total value of approximately USD 75 million.

The lawsuit claims that the properties are proceeds of sanctions violations and were used for international money laundering aimed at violating sanctions by Vladimir Voronchenko, who was indicted earlier.

In April 2023, Microsoft was ordered(35) to pay a USD 3.3 million civil fine in connection with the violation of the sanctions regime (by providing access to licensed software to Russian companies). Attempts to export dual-use equipment to Russia resulted in criminal charges and confiscation of about USD 826 thousand for the individuals and companies involved(36). A Russian citizen, Ilya Balakayev, was charged(37) with smuggling devices intended for use in counter-intelligence and military operations from the United States to Russia for the FSB.

All of these cases, as well as the adoption of legislative changes that allow for the transfer of assets confiscated as part of the sanctions circumvention to Ukraine, show that the United States, unlike our European partners, is already actively using mechanisms to bring individuals to justice for such actions, with the perspective of using the funds for compensation.

Section III

Liability for sanctions evasion in Ukraine. “Homework” to be done

In response to the annexation of Crimea and support for militants in Donbas in 2014, Ukraine adopted the sanctions legislation and began to actively enforce it.

After Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022, the sanctions legal framework was significantly strengthened, including the possibility of confiscating the assets of sanctioned persons in court(38).

At the same time, no relevant amendments to the criminal law have been adopted to establish special liability for violation of sanctions.This may be due to the fact that such actions often contain elements of other criminal offences and can be prosecuted under other articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (CCU), mostly of economic nature.

However, exerting global pressure on sanctioned persons and the synchronisation of sanctions lists among partner countries and Ukraine require unification of legislation.

The absence of a special provision that would establish criminal liability for circumvention of sanctions in Ukraine, firstly, looks questionable given the current trends in the general criminalisation of such acts among partners, and, secondly, significantly limits the possibilities of international cooperation between law enforcement agencies.

Thus, it may be problematic to execute international orders or, for example, to confiscate the foreign assets of a sanctioned person when proceedings are opened in Ukraine under another article due to the absence of a special provision on violation of sanctions.

In order to remedy this situation, in January 2023, the Parliament registered Draft Law No. 8384 “Draft Law on Amendments to the Criminal and Criminal Procedure Codes of Ukraine and Other Laws on the Establishment of Criminal Liability for Violation of Sanctions Legislation”. However, as of the end of summer, the draft law is still under consideration and has not even been included in the agenda of the Parliament's session.

This draft law provides for amendments to the Criminal Code, namely, it adds a new Article 111-3, which establishes criminal liability for violation of the requirements of the sanctions legislation.

The actus reus of the offence is described in Part 1 and consists of “failure to comply with, hindering or evading the observance of special economic and/or other restrictive measures (sanctions)”. Parts 2-5 contain qualified offences based on the subject, form of complicity and consequences.

Other articles of the Criminal Code are also amended to recognise the commission of the said criminal offence as a ground for the application of special confiscation, as well as criminal law measures to legal entities. In addition, the Criminal Procedure Code of Ukraine is amended to assign jurisdiction over this criminal offence to investigators of security agencies and to allow for a special pre-trial investigation.

It should be noted that the proposed model of criminalisation of sanctions evasion contains several points for debate.

Firstly, the placement of the provision on violation of sanctions requirements in the system of the Special Part of the CC.

Thus, it is proposed to place this article in Section I “Crimes against the foundations of national security of Ukraine” of the Special Part of the Criminal Code, i.e. the generic object of the criminal offence will be the foundations of national security of Ukraine. In the explanatory note to the draft law, the authors justify this placement based on the legislative definition of sanctions applied to protect national interests, national security, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, countering terrorist activities, as well as preventing violations and restoring violated rights, freedoms and legitimate interests of Ukrainian citizens, society and the state(39). However, as we can see, sanctions can be applied not only to protect national interests. In addition, even the possibility of encroachment on the national interests of Ukraine, which are defined in the Law of Ukraine “On National Security of Ukraine”, does not automatically mean that there is an encroachment on the foundations of national security in the sense of the object of protection of the Criminal Code.

As rightly noted by scholars, national security covers various areas of regulation and virtually all areas of public administration, but only to the extent that it protects not just any, but vital (most important) interests. In the same way, but in relation to the CC provisions, the concept of " foundations" in the title of Section I of the Special Part of the CC has a restrictive meaning and indicates that the provisions of this section of the CC protect the most important relations (“foundations of foundations”)(40).

The law currently defines 31 specific types of sanctions, and the list is not exhaustive. Most of them, although they may pose a threat to national security, are not capable of encroaching on the foundations of national security. This applies, for example, to such types of sanctions as cancellation of official visits, meetings, negotiations on treaties or agreements; termination of cultural exchanges, scientific cooperation, educational and sports contacts, entertainment programmes with foreign states and foreign legal entities, etc. Obviously, failure to comply with or evasion of these sanctions cannot harm the foundations of Ukraine's national security.

Therefore, the place of the proposed rule in the system of the Special Part of the Criminal Code should be reconsidered. It seems that such an article could be placed, for example, in Section XV of the Special Part of the CC "Crimes against the authority of state bodies, local self-government bodies and associations of citizens", since it actually deals with obstruction of the administrative activities of state authorities responsible for the implementation of the sanctions policy.

Secondly, the shortcomings of the relevant legislation on the implementation of sanctions and the overly broad disposition.

The disposition of the proposed article is quite broad, since the actus reus of the offence consists in committing socially hazardous acts in the form of 1) failure to comply; 2) obstruction of compliance; 3) evasion of special economic and/or other restrictive measures (sanctions). Since there is no specification of such acts, they may include a variety of acts or types of inaction. Instead, the regulatory legislation on the application of sanctions contains gaps, conflicts and other shortcomings that objectively do not allow for the effective implementation of restrictive measures in practice. Under such conditions, the practice of implementing the said criminal prohibition will be complicated, and opportunities for unfair criminal prosecution will be created.

Thus, if only general criteria of the actus reus of the criminal offence are established, it is necessary for the regulatory legislation to be clear, unambiguous and effective.

Thirdly, the shortcomings of the proposed sanctions.

The authors of the draft law suggest applying a rather severe punishment for the said offence, which may not correspond to the degree of social dangerousness of the act and may introduce a disproportion in the existing system of punishment for criminal offences. For example, the simple offence set out in part 1 of the proposed article provides for imprisonment for a term of five to seven years, and the most qualified offence under part 5 - for a term of nine to twelve years. The same applies to fines (under Part 5 - up to 60,000 tax-free minimum incomes). Given the fundamental difference between different types of restrictive measures, as well as the "gravity" of crimes with similar sanctions, the proposed penalties seem excessive, especially given that such a provision will be in force not only during martial law, but also after its termination or expiration.

Therefore, it seems necessary to reconsider the proposed penalties.

Since sanctions violations usually involve significant assets or profits, it would also be appropriate to expand the applicability of non-conviction based forfeiture to criminal assets related to sanctions evasion. It will allow for quick and efficient confiscation of assets that were obtained as proceeds of sanctions evasion or that were attempted to be moved out of the sanctions without the need to wait for a court verdict in criminal proceedings. This procedure is currently used in the process of confiscation of unexplained assets and has proven to be effective in practice(41).

In general, the issue of Ukraine's completion of its “homework” in the form of criminalising sanctions evasion is long overdue, so the respective changes should be adopted as soon as possible. At the same time, it is necessary to adopt a balanced act free of legal flaws and shortcomings that could negatively affect law enforcement.

It is also important that the Ukrainian model of liability for sanctions evasion is as close as possible to the regulation of partner countries, in particular the EU, and the approaches set out in the Directive on the Violation of Restrictive Measures. All the more so given Ukraine's active European integration processes.

The idea of transferring assets and funds obtained as a result of criminal prosecution for sanctions evasion to compensate for war-related damage is also worth considering. In this way, Ukraine will set a good example, and concrete decisions in this area will serve as a guide for other states to ensure that the Compensation Fund is replenished and that real compensation is provided to victims.

(39) See the Law of Ukraine ‘On Sanctions’.

(40) Рубащенко М. А. Кримінальна відповідальність за посягання на територіальну цілісність і недоторканність України : монографія. Харків: Право, 2016. С. 21.

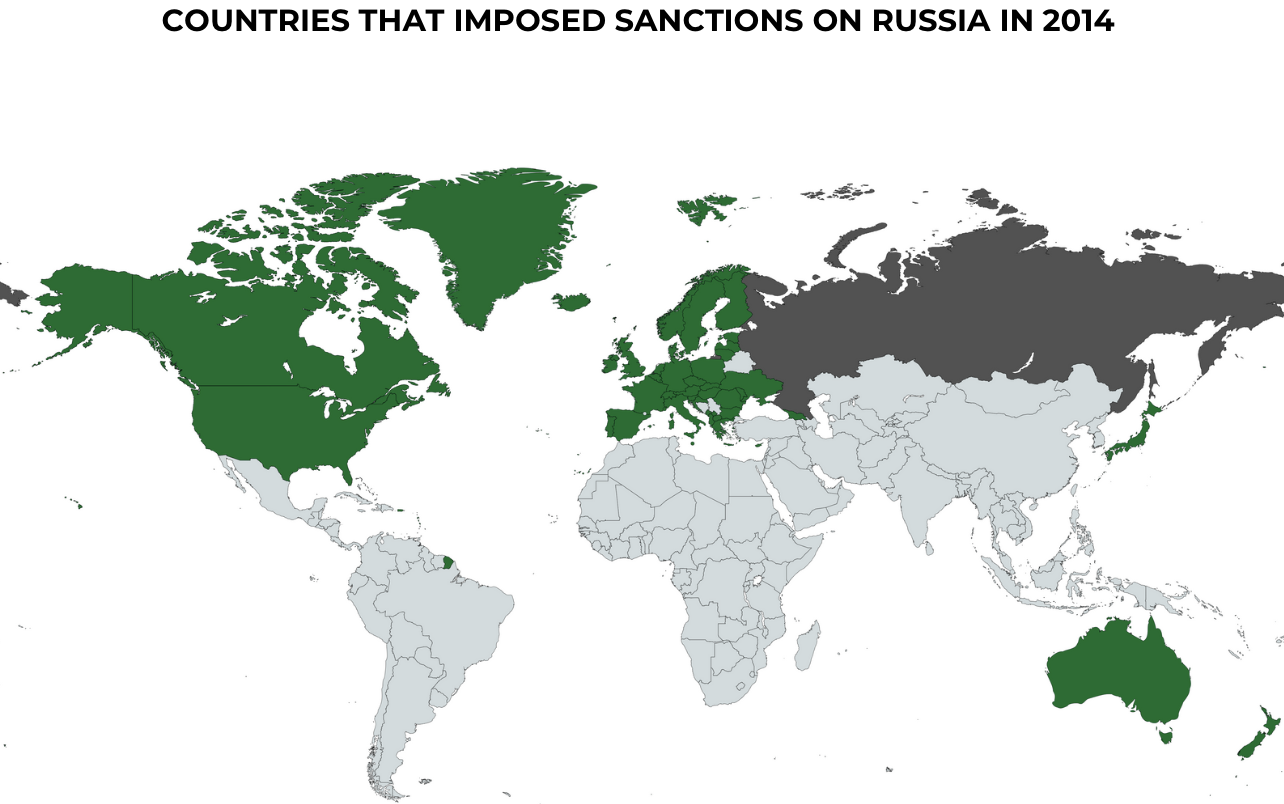

Conclusions and recommendations

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has provoked a tightening of the sanctions already imposed on Russia, the number of which has reached a record high. However, the restrictive measures are being exhausted, while the drive to circumvent them is only growing. It raises the issue of ensuring strict compliance with the sanctions already in place and closing existing loopholes. Strict liability for such actions could become a significant incentive to comply with sanctions discipline and a deterrent to those who intend to violate the restrictions. Understanding this, partner countries are demonstrating a tendency to change their policy on sanctions circumvention, in particular, by imposing severe criminal penalties on violators and striving to ensure the inevitability of punishment.

Given that sanctions evasion is usually cross-border (violators use several jurisdictions), it is essential to unify the legislation on sanctions evasion at the global level, which will close the possibility of exploiting jurisdictions with "lenient" penalties and enable an appropriate level of cooperation. The obligation of designated persons to declare assets should also be scaled up, and its violation should be recognised as a crime of sanctions evasion and be subject to special confiscation.

Contrary to the global course of toughening responsibility for sanctions evasion, Ukraine has not yet done its homework to criminalise such actions. The relevant draft law has not been moving in the Parliament for several months, and it contains significant shortcomings that need to be addressed and revised.

Ukraine, as a victim of war, should set an example for other countries, including in the fight against sanctions evasion. To do so, it is necessary to adopt high-quality and effective legislation that would allow for successful combating sanctions evasion using the tools of criminal law repression. When developing such legislation, common approaches of partner states should be taken into account, to harmonise it, first of all, with the relevant EU norms, which will greatly facilitate proper international cooperation of authorised law enforcement agencies.

The process of prosecution for sanctions evasion may be accompanied by various asset forfeiture procedures, such as special confiscation of criminal instrumentalities or civil forfeiture in criminal proceedings. In addition, violators are subject to fines for such actions. Since all of this is actually a consequence of the war against Ukraine, it is only fair that this money be used to remedy the consequences of the aggression, namely to compensate for the damage caused. A similar approach has already been introduced into US law and is being implemented in practice.

We recommend that partner states provide in their legislation for the possibility of channeling the proceeds of sanctions evasion to compensate for the damage caused, in particular through the Compensation Fund (once it is established). Administrative and other costs incurred may be reimbursed from these proceeds, but should not exceed the amount transferred to the Fund. Ukraine should also enshrine this possibility by introducing relevant amendments to its legislation, including the budget one. It would be advisable for Ukraine and its partners to extend the non-conviction based forfeiture to criminal assets related to sanctions evasion. It would allow for quick, efficient and legal seizure of such assets and their subsequent use to compensate for the damage caused by the aggression.