>

Analysts>

Compensation for war-related moral damage: Ukrainian and international practiceCompensation for war-related moral damage: Ukrainian and international practice

This paper presents our analysis of the practice of compensation for non-pecuniary damage in Ukrainian law, as well as the UN Compensation Commission and the European Court of Human Rights.

The peculiarity of non-pecuniary damage is that it cannot be calculated precisely. Therefore, we have investigated who can claim compensation for moral damages, what emotional and psychological experience is recognized as legally compensable, and what the amount of such compensation can be paid.

Publisher: think tank “Institute of Legislative Ideas”. All rights reserved.

Authors: Tetiana Khutor, Bohdan Karnaukh, Andrii Klymosyuk

Cover photo by Konstantin and Vlada Liberovy, project “On the ruins with hope. We will win”

Introduction

Summary

Tort law is concerned with the repair of wrongfully inflicted damage. Its purpose is to restore the position of the injured person as if the wrongdoing had not occurred (restitutio in integrum). To the extent possible, compensation should be such as to "return" the injured person to the position he or she would have been in but for the harmful incident.

However, time cannot actually be "rewound" in the literal sense of the word. So, even when the negative consequences in the physical world are repaired (the damaged property is restored or replaced with a new one), the negative experience that the person has undergone - the painful feelings, emotions, and distress - remains with the person. And the fact that the property is now safe and sound does not negate the time spent in worry, anxiety, and stress.

This is even more true in cases of damage to life and limb. Even when the victim makes a full recovery and the economic consequences of their injury (such as medical expenses and lost earnings) are fully covered by the tortfeasor, the pain and suffering experienced remains unaddressed. This experience can be a depressing, indelible pain, and a trauma that stays for life.

Moral damage is a legal term intended to provide compensation for adverse, traumatic experiences.

Often, the same incident causes damage on two levels at the same time - on the economic and moral (non-pecuniary) levels. For example, if the victim's arm is broken, this entails economic damage in the form of treatment costs, loss of earnings (income) due to a decrease in professional or general ability to work, additional costs for prosthetics, third-party care, etc. and non-pecuniary damage in the form of pain, discomfort, inconvenience, etc. In order to fully restore the situation of the injured person, tort law provides for the possibility of claiming compensation for both economic and moral (noneconomic) damage.

However, with regard to non-pecuniary damage, there are a number of questions that remain problematic for lawyers and that have not received (and perhaps cannot receive) clear, unambiguous answers.

These include:

- the minimum threshold of compensable negative experience;

- determining the amount of monetary compensation for pain and suffering;

- the degree to which individual traits are taken into account when assessing the severity of the experience;

- evintiary standards for proving non-pecuniary damage.

Russian aggression against Ukraine has impacted every Ukrainian without exception. There is no Ukrainian who has not gone through this war as a distressing experience. The war impinges on each of us: at the very least, it makes everyone constantly fear for their lives and the lives of their loved ones, deprives of confidence in the future, and disrupts settled routines and life projects. But these are the least of the misfortunes brought by the war. It takes lives, maims, destroys homes and entire cities, ruins cultural heritage, and hurts the environment.

Section I

Ukrainian practice

In April 2022, the Supreme Court passed a landmark ruling(1) according to which the Russian Federation cannot invoke jurisdictional immunity in cases concerning compensation for war-related damage (previously, claims against the Russian Federation could be tried by Ukrainian courts only upon the consent of the Russian Federation itself)(2).

This finding enabled Ukrainian citizens to sue the aggressor state in Ukrainian courts. As a result, a new category of cases has emerged in Ukrainian jurisprudence - cases concerning compensation for war-related damage, in which the Russian Federation is the defendant.

Quite often in such cases, plaintiffs seek compensation for moral damage. Moral damage can be incurred as a result of the death of a family member, injury, bodily harm, loss of property or loss of use of property, or internal displacement that disrupted the plaintiff's normal mode of life.

Here are some examples of how Ukrainian plaintiffs substantiate moral damage caused by Russian aggression.

In case No. 308/9708/19, the claim was substantiated by the fact that the plaintiff's husband, a Ukrainian serviceman, was killed during a combat mission when the occupying power's mercenaries shelled Luhansk airport with BM-21 Grad.

The plaintiff stated that "as a result of these events, she and her children suffered moral damage. As a result of the loss of her husband and father, who died as a result of the Russian military aggression against Ukraine, and given the particular cynicism with which the Russian Federation violates fundamental human rights and freedoms in Ukraine, she and her children experience continuous, unrelenting mental pain and suffering. They have lost their peace of mind and faith in the future, constantly feel insecure and frustrated, which makes it impossible to communicate normally with others and maintain a normal lifestyle."

In case No. 344/10421/22, the claim was substantiated by the fact that the plaintiff "had lived in Kherson since birth, and in 2022 was planning a wedding and buying her own home. The aggressor state occupied the city, and the plaintiff lived under occupation, and in April 2022 she decided to move. She states that she experienced stress while leaving the occupied territory, constantly fearing for her life. These circumstances led to moral and mental suffering, as she was forced to change her usual way of life, left her own home, where her parents remained."

In case No. 509/3494/22, the claim was substantiated by the fact that the plaintiff "purchased an apartment in her hometown of Mykolaiv in early 2021... On 12.06.2021, the plaintiff got married, after which she and her husband began to arrange family life, carry out repairs for further, comfortable living in a new home, and plan a pregnancy. Around October 2021, the plaintiff became pregnant. On 02/23/2022, the plaintiff underwent a second ultrasound to determine the sex of the fetus. On 02/24/2022, the war broke out due to the armed aggression of the Russian Federation. From the very beginning, she was in a state of constant stress: at 5 a.m. on 24.02.2022, she woke up from explosions near the Kulbakino airfield, until early April she and her family were in Mykolaiv, about a third of the time she had to stay in the basement of the house, hiding from enemy artillery shelling. In early April, after an MLRS missile hit her home and damaged her apartment, the plaintiff decided to leave her hometown and home and temporarily move to Odesa. At that time, the plaintiff was already 6 months pregnant, which made it difficult for her to move around and go down to the basement every time. At the time the missile hit near her house, the plaintiff barely had time to leave her apartment, which was hit by debris 20 seconds later. All this time, the plaintiff was worried about the possibility of a negative impact of excessive stress on the child's condition, worried about her own life, the lives of her husband and parents."

In case No. 641/3306/23, "The armed aggression resulted in the loss of the plaintiff's property and housing, protection and hope for returning home. Before leaving the territory occupied by the Russian Federation, the plaintiff was a valued member of society, had a well-established routine and the opportunity to lead a fulfilling life. However, with the beginning of the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, she was deprived of such opportunities. In order to avoid massive human rights violations, the plaintiff left the territory of her place of registration/residence occupied by the Russian Federation and moved to another city in Ukraine. After the move, she had to adapt to new living conditions, find a job, housing and restore her standard of living. The plaintiff was deprived of her usual rhythm of life, communication with family and friends, as well as the opportunity to return home and regain her normal life. Justifying the moral damage caused by the defendant in the amount of 70,000 euros, the plaintiff states that this is a fair compensation from the aggressor, the Russian Federation, for the violation of fundamental human rights in Ukraine, which caused the plaintiff to suffer mental anguish and continuous suffering due to the war."

The definition of moral damage and general rules for its compensation are set forth in Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine:

"1. A person has the right to compensation for moral damage caused by a violation of his or her rights.

2. Moral damage includes:

1) physical pain and suffering experienced by an individual due to a maim or other injury;

2) mental anguish suffered by an individual due to unlawful behavior towards him or her, members of his or her family or close relatives;

3) mental anguish suffered by an individual due to the destruction or impairment of his or her property;

4) humiliation of the honor and dignity of an individual, as well as the business reputation of an individual or legal entity.

3. Unless otherwise provided by law, moral damage shall be compensated in cash, other property or in another way.

The amount of pecuniary compensation for moral damage shall be determined by the court depending on the nature of the offense, the depth of physical and mental suffering, deterioration of the victim's abilities or deprivation of their realization, the degree of fault of the person who caused moral damage, if fault is the basis for compensation, as well as taking into account other circumstances of significant importance. In determining the amount of compensation, the requirements of reasonableness and fairness shall be taken into account.

4. Moral damage shall be compensated regardless of the pecuniary damage subject to compensation and is not dependent on the amount of such compensation.

5. Moral damage shall be compensated in a lump sum, unless otherwise provided by the agreement or law."

Many clarifications regarding moral damage were provided by the highest courts. (3)

Particularly significant was the legal position of the Grand Chamber of the Supreme Court in case No. 216/3521/16-ц, in which compensation for moral damage was recognized as a universal remedy, i.e., one that applies to all legal relationships, not only when it is expressly provided for a particular situation by a special law or contract:

"92. Proceeding from the provisions of Articles 16 and 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine and the content of the right to compensation for moral damage in general as a way of protecting the subject's civil right, compensation for moral damage should be awarded in any case when it is inflicted - the right to compensation for moral (non-pecuniary) damage arises as a result of violation of a person's right without the need for special provisions in civil legislation".

In case No. 496/1691/19, the Civil Court of Cassation added:

"The interpretation of Article 23 of the Civil Code of Ukraine demonstrates that it is a rule that should apply to any civil law relationship in which a person has suffered moral damage. This is, in particular, confirmed by the fact that the legislator uses the wording "a person has the right to compensation for moral damages caused by a violation of his or her rights". In other words, the possibility of recovering compensation for moral damages is made dependent not on the fact that it is provided for by a provision of law or a contract, but on the violation of a person's civil right."

Thus, moral damage is always subject to compensation, provided that it is caused by unlawful decisions, actions or omissions (see Article 1167 of the Civil Code of Ukraine). However, the plaintiff in such cases must prove that he or she has actually suffered moral damages. And since the very concept of moral damages is evaluative (since not every negative experience is severe enough to give rise to the right to compensation), the case law on this issue remains heterogeneous.

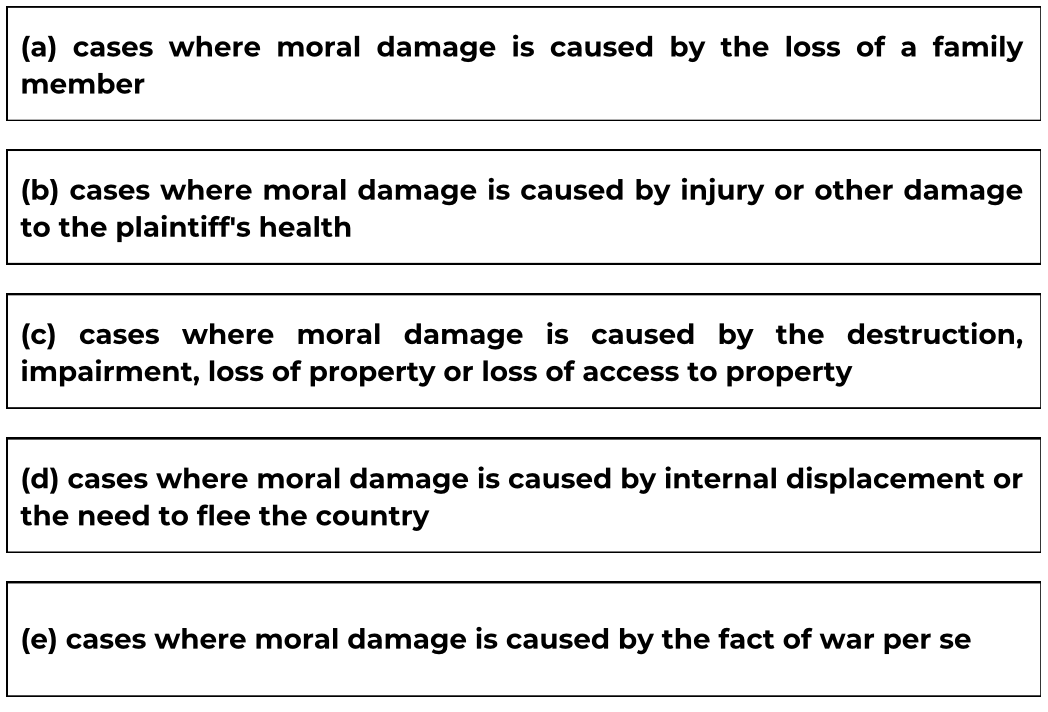

All cases involving moral damage caused by the war can be divided into five categories:

As for categories (a), (b) and (c), in these cases, the presence of moral damage is usually not in dispute, and the only challenging issue is the calculation of the amount of compensation. Instead, in categories (d) and (e), the courts sometimes take opposite views.

Thus, for the most part, the courts uphold claims where moral damage is caused by internal displacement or the need to flee the country (category (d)).

However, there are also cases in which the courts arrive at the opposite conclusion. For example, the Oleksandriya City and District Court of Kirovohrad Region in its decision of January 10, 2023 in case No. 398/3995/22 stated:

"In view of the foregoing, the court notes that neither the laws and regulations of Ukraine nor the international legal acts applicable in the event of the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, such as the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of 1950, the Geneva Conventions with Additional Protocols thereto and the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property of 2004 do not contain a norm that would oblige a certain party to the conflict to compensate for non-pecuniary damage to a person due to the very fact of such an armed conflict or due to the temporary displacement of a person from the zone of active hostilities to a safe territory.

Thus, the court notes that the existing international and national legal acts do not contain provisions on the right of a temporarily displaced person to compensation from the aggressor state for moral suffering incurred due to such displacement."

However, on appeal, this decision was overturned and the claim was satisfied.

It is noteworthy that in many cases where plaintiffs claim compensation for moral damage caused by the displacement, the amount of compensation is estimated at 35 thousand euros. This figure comes from the case of Loizidou v. Turkey, which was considered by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), and will be discussed in detail further.

As for the last category (d), these are cases in which the plaintiffs refer to the fact of Russia's invasion of Ukraine as a stress factor and claim that non-pecuniary damage consists of the severe experiences they had to endure in connection with the war. No other personal or financial damage, including the need for internal displacement, is alleged. Some of these cases have even been publicized in the press.

For example, in case No. 753/15426/20, the claims were substantiated by the following

"On February 20, 2014, the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against the state of Ukraine was launched, which resulted in the occupation by the Russian Federation of part of the territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine.

As a result of the above, the plaintiff suffered mental anguish, deteriorated health, and decreased vitality. The plaintiff also notes that she is constantly in a depressed state, which has negatively affected her relationships with others and led to a deterioration in normal life ties. Since February 2014, the plaintiff has been listening to and reading the news on a daily basis, which reports on the deaths and injuries of people, as well as explosions and destruction of buildings, the seizure and torture of hostages in the war zone in the East of Ukraine. He explains the deterioration of his mental state by the fact that while in public transport and outside he often meets disabled people and unwittingly witnesses funeral processions for the fallen defenders of Ukraine. The plaintiff is painfully aware of the fact that the economy of Donbas is completely destroyed, which negatively affects her standard of living, and also notes the flooded mines that threaten a major environmental disaster, which endangers the health of the plaintiff and her fellow citizens.

Due to the above, the plaintiff had to file this lawsuit and seeks to recover in her favor from the Russian Federation moral damages in the amount of UAH 100,000.00".

The Darnytsia District Court of Kyiv dismissed the claim, reasoning that the plaintiff had not proved the moral damage:

"Thus, the plaintiff did not provide any evidence to prove the moral damage, there is none in the case file, and the plaintiff's allegations in the statement of claim about her constant depression, which negatively affected her relationships with others and led to a deterioration in normal life ties, are based only on assumptions, i.e. the plaintiff has not proved the existence of moral suffering".

In this case, the plaintiff was not disingenuous - the war indeed affected every Ukrainian. Even people who have not suffered the bitter loss of loved ones, injury or other bodily pain, or lost their property, are going through a psychologically difficult experience.

However, if this experience is recognized as legally compensable, then every person living in Ukraine would have the right to go to court. Moreover, the range of potential victims would not be limited to the physical borders of Ukraine - anyone who cares about Ukraine could be a victim, because they also experience hard feelings. Therefore, if tort law were to recognize the claims of such people as eligible, it would open the door to tens of millions of claims that the national judicial system could hardly handle.

Secondly, unlike other categories of cases where moral damage is incidental to other (bodily or economic) damage, in category (d) moral damage is the only type of damage claimed by the plaintiff.

Is it possible for moral damage to occur on its own, and not as a "concomitant consequence" of some other (bodily or economic) damage? Yes. For example, in the case of humiliation of the honor and dignity of an individual ( in the case of dissemination of false information about a person).

However, even in such cases, moral damage must be the result of a violation of a concrete right enjoyed by a concrete person (the right to inviolability of honor, dignity and business reputation). In contrast, an aggressive war to seize territories is a violation of the sovereignty of a particular state, not a violation of the rights of a particular citizen of that state. Therefore, the mere fact of an aggressive war against Ukraine, in the absence of any other bodily or economic harm or other observable inconveniences (such as the need to leave one's home), does not entitle a Ukrainian citizen to claim compensation for moral damage under the rules of tort law.

Section II

The United Nations Compensation Commission’s practice

The United Nations Compensation Commission (hereinafter referred to as the Commission) was established in 1991 pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 692 to consider claims and pay compensation for damage and losses caused by Iraq's illegal invasion of Kuwait and subsequent occupation of Kuwait in 1990-1991.

It is important to note that the Commission's role was more administrative than judicial in nature. Its task was mainly to establish the facts and determine the amount of compensation.

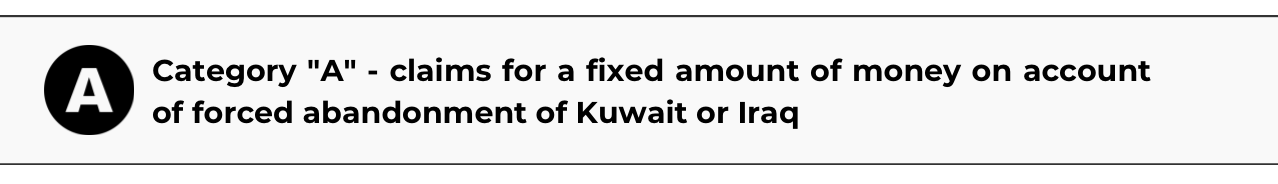

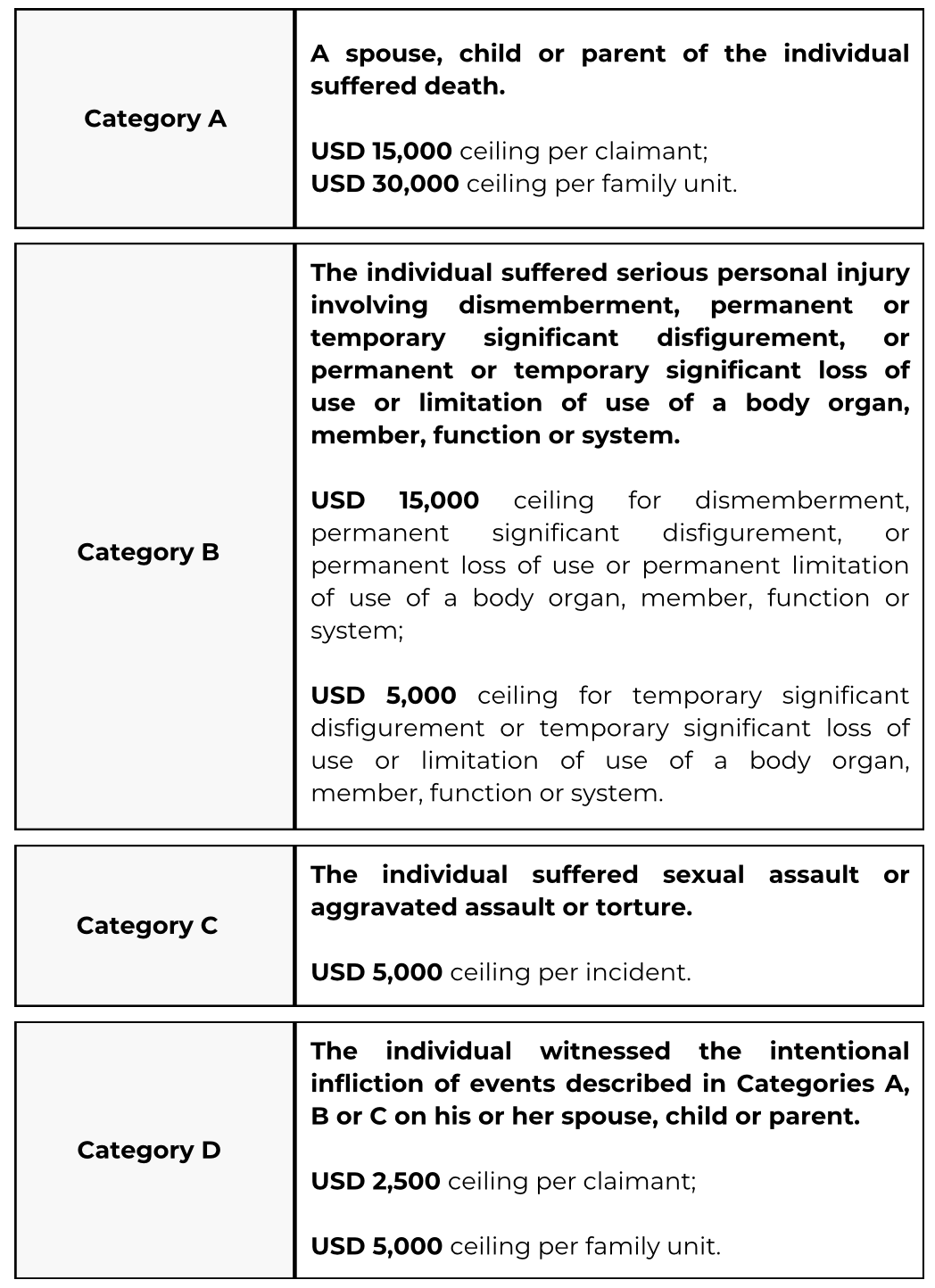

The Governing Council has defined six categories of claims:

These claims were filed by people who were forced to leave Kuwait or Iraq between August 2, 1990 (the day of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait) and March 2, 1991 (the day of the ceasefire). The amount of compensation for this category was fixed at USD 2,500 per person and USD 5,000 per family. However, if the applicant did not claim compensation under any other category, the amount was USD 4,000 and USD 8,000, respectively.

The amount of compensation for such claims was USD 2,500 per person and USD 10,000 per family. However, if a person believed that this amount was not sufficient to remedy the damage, he or she could also file a category C claim.

This category included eight subcategories:

C1: Damages arising from departure from Iraq or Kuwait, inability to leave Iraq or Kuwait, a decision not to return to Iraq or Kuwait, hostage taking or other illegal detention;

C2: Damages arising from personal injury;

C3: Damages arising from death of [the claimant's] spouse, child or parent;

C4: Personal property losses;

C5: Loss of bank accounts, stocks and other securities;

C6: Loss of income, unpaid salaries or support;

C7: Real property losses;

C8: Individual business losses.

The types of damage were the same as in category "C".

The types of damage were the same as in category "C".

Such claims related to losses under construction or other contracts, losses from non-payment for goods or services, losses related to the destruction or seizure of business assets, lost profits, losses in the oil sector, etc.

Such claims related to losses under construction or other contracts, losses from non-payment for goods or services, losses related to the destruction or seizure of business assets, lost profits, losses in the oil sector, etc.

Such claims covered the costs incurred by states in evacuating their citizens, providing them with aid, damages in connection with the destruction of diplomatic buildings, loss or damage to other state property, as well as environmental damage and depletion of natural resources in the Gulf region, including as a result of oil well fires and oil dumps into the sea.

In addition to compensation for pecuniary losses, in designated cases, applicants were also entitled to claim compensation for moral damage, or - in the Commission's own terminology - compensation for mental pain and anguish (MPA).

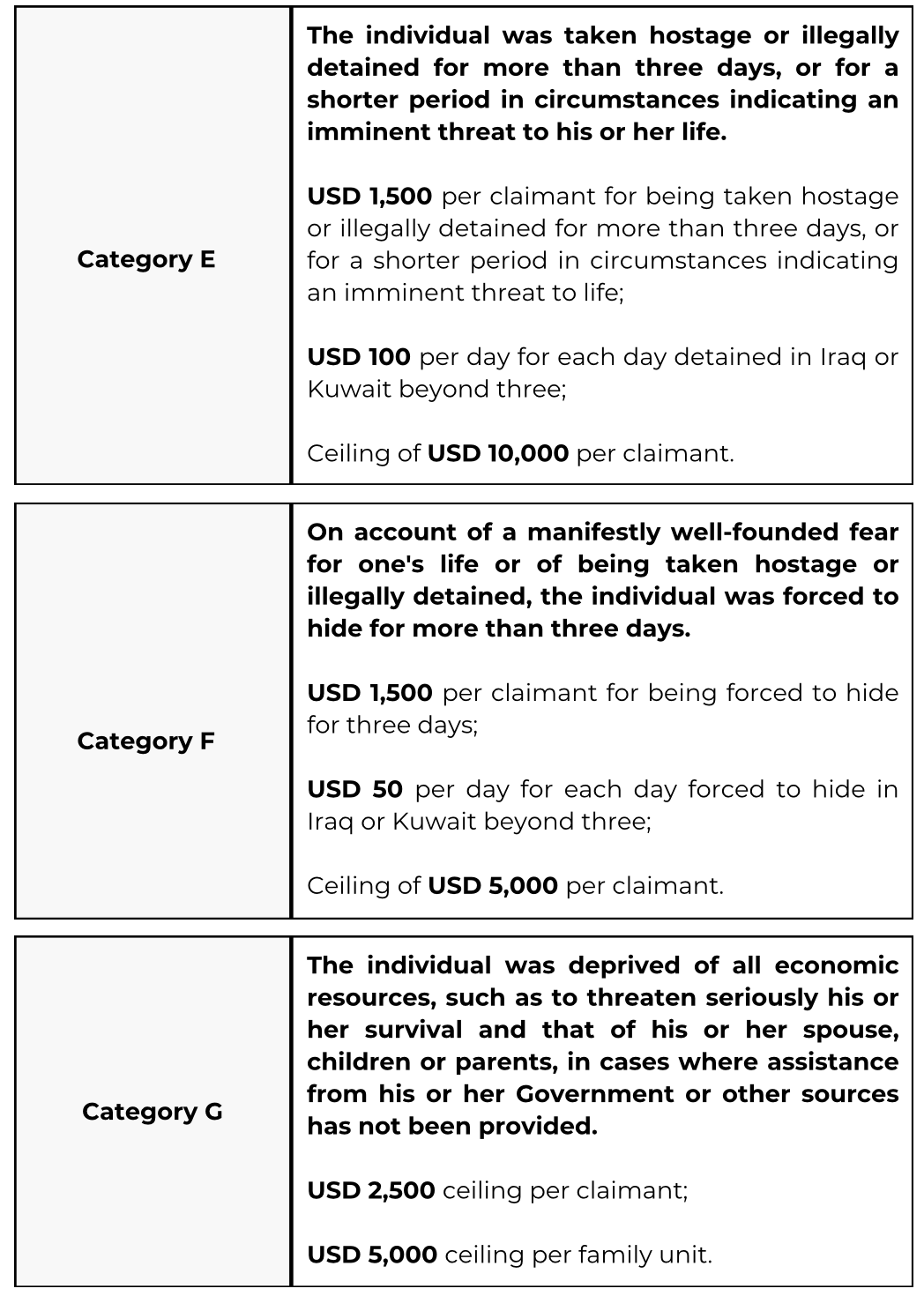

The list of such cases and the maximum amount of compensation was set out in Decision No. 8.

One person was entitled to claim compensation for moral damage in several categories at once, with the final number calculated as the sum of compensation for all claimed categories. However, the overall maximum award for moral damage was USD 30,000 per claimant and USD 60,000 per family.

With regard to the Commission's practice, it is important to note, first, that not in all cases of pecuniary damage, the victims were recognized as having the right to additionally claim compensation for non-pecuniary damage.

Second, in those specified cases in which the victims were entitled to compensation for non-pecuniary damage, no additional evidence was required to prove mental pain or suffering. Thus, applicants had to prove only the fact of a traumatic incident (serious bodily injury, sexual violence, torture, etc.), and the occurrence of non-pecuniary damage in such cases was accepted as an irrefutable presumption. There was no need to prove mental suffering separately, by means of an expert opinion.

At the same time, in Decision No. 3, the Commission's Governing Council emphasized the need to distinguish between "mental pain and suffering" (i.e. non-pecuniary damage), on the one hand, and "mental injury", on the other. If the events of the war had such a severe impact on a person's mental state that he or she developed a condition that qualifies as a mental disorder (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder), then such a disorder should be treated as an independent type of damage in category "B" - serious bodily injury, and it is subject to separate proof. In this case, the concept of mental disorder should be understood in accordance with the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases.

The Report of the Panel of Experts appointed to assist the UN Compensation Commission in matters relating to mental pain and suffering deserves special attention(5). This panel included leading psychiatrists whose task was to help the Commission determine guidelines for compensation for non-pecuniary damage.

It is noteworthy that in this Report, the experts specifically emphasized that the conclusions they made could be useful not only for the work of the Commission, but also for similar compensation mechanisms in the future, when it comes to assessing moral damage caused by armed conflicts:

“II. The situations described in Categories A, B, C, D and G of Decision 8 were unfortunately likely to occur again in other instances of war and similar catastrophes. The recommendations that are being made by the Panel members have therefore been put forward with an awareness that the procedures recommended for the assessment of mental pain and anguish may well be used in other compensation programmes that the United Nations and other bodies might undertake in the future;”

Experts also noted that the maximum compensation limits set by the Compensation Commission are generally low. However, it should be realized that these amounts are not a universal and accurate measure of the suffering caused - they are the result of considering numerous political, economic and practical factors:

“In view of these basic principles, the Panel members recommend that any financial compensation be accompanied by appropriate statements to ensure that the victims understand that the provision of money also has the function of recognizing that they have been exposed to situations causing severe mental pain and anguish, and that the sums provided were limited by the Commission for a variety of practical, political and economic reasons rather than by the nature of experiences suffered;” (page 259)

An important outcome of the experts' work was the development of "Modifying Factors", i.e., circumstances to be taken into account when determining the exact amount of compensation to be awarded within the maximum cap. The Modifying Factors serve as guidelines to help determine whether the amount awarded in each case should be closer to the maximum or minimum limit.

In particular, in respect of category A non-pecuniary damage (death of a family member), the claimant is entitled to a minimum amount of USD 5,000, regardless of any other circumstances and without the need to provide any further explanation.

I) The claimant is less than 21 years old and loses both parents;

II) The claimant is less than 21 years old and loses his or her only parent;

III) The death of the claimant's family member occurred as a result of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (e.g., death as a result of torture, execution, sexual assault or being held as a "human shield").

I) Multiple losses suffered by claimant (e.g., in addition to the death of the claimant's family member, the claimant suffered (another) one of the events described in Categories A, B or C of Decision 8);

II) Intentionality of actions or events by officials, employees, members of the armed forces or other agents of Iraq leading to the death of the claimant's family member (other than those events described in 2. (III);

III) Degrading burial or other improper treatment of the deceased family member's body (e.g., no burial; family members not present; corpse not buried in accordance with religious practice or cultural expectations of the claimant or the deceased; enforced period of time lapses between death and burial; or improper treatment of body);

IV) Non-recovery of diseased family member's body;

V) Loss of family member who is the only child;

VI) Loss of primary family support-earner;

VII) Lack of medical care due to the invasion and occupation of Kuwait contributed to the death of the claimant's family member.

In this case, torture should be understood in accordance with the definition in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment:

“the term "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions”.

Furthermore, being forced to witness the intentional infliction of harm on a family member also constitutes torture, and thus entitles the applicant to compensation in accordance with the formula developed for category C.

(I) has one or more dependent family members (including a spouse, child or parent)

(II) has suffered a serious injury or illness of such a nature that it prevents him or her from performing his or her profession or job function.

Section III

Case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)

General principles on compensation for non-pecuniary damage applied by the ECtHR are set out in the Practice Directions on Just Satisfaction:

«10. The Court’s award in respect of non-pecuniary damage serves to give recognition to the fact that non-material harm, such as mental or physical suffering, occurred as a result of a breach of a fundamental human right and reflects in the broadest of terms the severity of the damage. Hence, the causal link between the alleged violation and the moral harm is often reasonable to assume, the applicants being not required to produce any additional evidence of their suffering.

11. It is in the nature of non-pecuniary damage that it does not lend itself to precise calculation. The claim for non-pecuniary damage suffered needs therefore not be quantified or substantiated, the applicant can leave the amount to the Court’s discretion.

12. If the Court considers that a monetary award is necessary, it will make an assessment on an equitable basis, which above all involves flexibility and an objective consideration of what is just, fair and reasonable in all the circumstances of the case, including not only the position of the applicant as well as his or her own possible contribution to the situation complained of, but the overall context in which the breach occurred.»

Thus, the ECtHR notes that applicants are not required to submit additional evidence to prove their mental suffering - the conclusion that such suffering was present is a natural inference when a person has proven a violation of his or her fundamental rights. Secondly, the ECtHR notes the impossibility of accurate calculation of non-pecuniary damage. At the same time, the Court emphasizes that the approach must be flexible and take into account all the relevant circumstances of the case.

In particular, the Court mentions the following circumstances as relevant:

- the nature and gravity of the violation found, its duration and effects;

- whether there have been several violations of the protected rights;

- whether a domestic award has already been made or other measures have been taken by the Respondent State that could be regarded as constituting the most appropriate means of redress;

- any other context or case-specific circumstances that need to be taken into account.

Finally, the ECtHR holds that the amount of compensation is dependent on the overall economic situation in the respondent state:

“14. Furthermore, as an aspect of “just satisfaction” the Court takes into account the local economic circumstances in the Respondent States in its calculations. In doing so, it has regard to the publicly available and updated macroeconomic data, such as that published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In view of these changing economic circumstances for the countries concerned, the amounts of awards made to injured parties in similar circumstances could vary in respect of different Respondent States and over a period of time.”

Effectively, this means that the amount of compensation for moral damages under the same circumstances will be different for applicants from different countries: in richer economies, the amount will be higher than in less wealthy ones. This is because just satisfaction is not intended to equalize global economic inequality, but only to remedy the situation of a particular claimant living in concrete economic conditions.

As noted above, Ukrainians in their claims against the Russian Federation often refer to the ECtHR judgment in Loizidou v. Turkey, which concerned Turkey's occupation of Northern Cyprus.

In this case the applicant, a Cypriot national, grew up in Kyrenia in northern Cyprus. She owned ten plots of land in Kyrenia. Prior to the Turkish occupation of northern Cyprus on 20 July 1974, work had commenced on one of the plots for the construction of a block of flats, one of which was intended as a home for her family. The applicant had entered into an agreement with the property developer to exchange her share in the land for an apartment of 100 sq. m. Yet, since1974 she has been prevented from gaining access to her properties in northern Cyprus and “peacefully enjoying” them as a result of the presence of Turkish forces there.

The ECtHR held that there had been a violation of Article 1 of Protocol No.1, as the applicant had effectively lost any control over her property, as well as all possibilities to use and dispose of it. In addition to the pecuniary damage (300,000 Cypriot pounds) in the form of lost profits that the applicant could have received by leasing her land plots, the ECtHR awarded non-pecuniary damage in the amount of 20,000 Cypriot pounds, equivalent to 35,000 euros.

Despite the fact that Ukrainian courts often award the same amount to internally displaced persons, it is worth noting that this amount was determined by the ECtHR based on the specific circumstances of the case under consideration. Such circumstances include, in particular, the amount of property to which the applicant lost access (ten land plots), its value, the amount of financial damage (over half a million euros), and the duration of the violation (the Court took into account the period from 1990 to 1997). Therefore, this amount should not be considered as a " default rate" of moral damages for all internal displacement cases.

For the Ukrainian situation, the findings of the ECHR in the case of Georgia v. Russia may be helpful. This case concerned the detention, custody and expulsion from Russia of a large number of Georgian citizens from the end of September 2006 to the end of January 2007. According to the Georgian government, during this period, the Russian authorities issued more than 4,600 expulsion orders against Georgian citizens, of whom more than 2,300 were detained and forcibly expelled, and the rest left the country on their own. The Court found that the expulsion of Georgian nationals during the period under review was not based on a reasonable and objective consideration of the circumstances of each individual's case, but instead constituted an arbitrary administrative practice in violation of Article 4 of Protocol No. 4 to the Convention.

It was also held that the lack of effective and accessible remedies for Georgian citizens violated Article 5 § 4 of the Convention, while the conditions of detention in which Georgian citizens were placed (overcrowding, inadequate sanitary and hygienic conditions and lack of privacy) constituted an administrative practice in violation of Article 3 of the Convention. The Court also found a violation of Article 13 in conjunction with Article 5(1) and Article 3 of the Convention.

Regarding the compensation for non-pecuniary damage in this case, the ECtHR noted that in some cases, the mere recognition by the Court that the applicant's rights have been violated is sufficient to remedy non-pecuniary damage, but in other cases it is not enough and compensation must be awarded. This case falls into the second category.

The Court noted:

“73. The Court reiterates that there is no express provision for awards in respect of non‑pecuniary damage in the Convention. In Varnava and Others v. Turkey [GC], nos. 16064/90 and 8 others, § 224, ECHR 2009, Cyprus v. Turkey (just satisfaction), § 56, and Sargsyan and Chiragov (§§ 39 and 57 respectively), cited above, the Court confirmed the following principles which had been gradually developed in its case-law. Situations where the applicant has suffered evident trauma, whether physical or psychological, pain and suffering, distress, anxiety, frustration, feelings of injustice or humiliation, prolonged uncertainty, disruption to life, or real loss of opportunity can be distinguished from those situations where the public vindication of the wrong suffered by the applicant, in a judgment binding on the Contracting State, is an appropriate form of redress in itself. In some situations, where a law, procedure or practice has been found to fall short of Convention standards this is enough to put matters right. In other situations, however, the impact of the violation may be regarded as being of a nature and degree as to have impinged so significantly on the moral well‑being of the applicant as to require something further. Such elements do not lend themselves to a process of calculation or precise quantification. Nor is it the Court’s role to function akin to a domestic tort mechanism court in apportioning fault and compensatory damages between civil parties. Its guiding principle is equity, which above all involves flexibility and an objective consideration of what is just, fair and reasonable in all the circumstances of the case, including not only the position of the applicant but the overall context in which the breach occurred. Its non-pecuniary awards serve to give recognition to the fact that non-pecuniary damage occurred as a result of a breach of a fundamental human right and reflect in the broadest of terms the severity of the damage.

74. In the present case there is no doubt that the group of at least 1,500 Georgian nationals who were victims of a violation of Article 4 of Protocol No. 4, and those among them who were also victims of a violation of Article 5 § 1 and Article 3 of the Convention, in the context of the “coordinated policy of arresting, detaining and expelling Georgian nationals” put in place in the Russian Federation in the autumn of 2006, suffered trauma and experienced feelings of distress, anxiety and humiliation during that period.

75. Accordingly, despite the large number of imponderable factors – due, among other things, to the passage of time – that come into play here, compensation for non-pecuniary damage can be awarded.

As a result, the ECtHR ruled that Russia should pay Georgia EUR 10 million in compensation for the damage suffered by a group of at least 1500 Georgian citizens; this amount should be distributed among individual victims in the amount of EUR 2,000 to Georgian citizens who were victims of a violation of Article 4 of Protocol No. 4 to the Convention (collective expulsion) only, and EUR 10,000 to 15,000 to those who were also victims of violations of Article 5, paragraph 1 (unlawful detention) and Article 3 (inhuman and degrading treatment) of the Convention, taking into account the length of their respective detention periods.

The damage caused by the armed conflict was also addressed in the case of Chiragov and Others v. Armenia [GC].The applicants in this case were Azerbaijani Kurds living in the Lachin region of Azerbaijan. They claimed that they could not return to their homes and property after being forced to leave them in 1992 during the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. The Court concluded that Armenia had violated Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the ECHR (right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions) and Article 8 of the ECHR (right to respect for private and family life).

Assessing the amount of both pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage in this case was complicated by a number of unknown or unconfirmed circumstances. In particular, the case file did not contain sufficient evidence to show that the applicants' houses still existed as of April 2002 and, if so, in such a condition that they could be taken into account for the purposes of awarding compensation. It was also extremely difficult to determine the value of the applicants' land. Therefore, the usual approach of calculating economic damage based on the expected rent for the relevant period and the income from agriculture and livestock cannot be applied in such circumstances.

No evidence, other than witness testimony, has been provided to support allegations of the loss of household items, cars, fruit trees, bushes and livestock. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that all of these items were probably destroyed or disappeared during the attack on the Lachyn district or during the subsequent ten-year period until April 2002. If some items still existed as of that date, they most likely deteriorated, died, or were no longer usable over time. The loss of wages and other income was not related to the lack of access to the applicants' property and housing, but to the applicants' displacement from Lachin in 1992. In this context, it was impossible to determine what kind of job or income the applicants could have had in Lachin in 2002, ten years after their flight.

Therefore, the ECtHR proceeded from the premise that a decision on compensation for pecuniary damage could be made only on two counts, namely, the loss of income from the applicants' land in Lachin and the increase in their living expenses in Baku. However, the assessment of the damage suffered depended on a large number of unknown circumstances, partly because the claims were generally based on a very limited evidentiary basis. As a result, the pecuniary damage suffered by the applicants could not be accurately calculated.

With regard to non-pecuniary damage, the ECtHR concluded that the circumstances of the case had clearly inflicted emotional suffering and stress on the applicants due to the prolonged and unresolved situation that separated them from their homes and property in the Lachin district and forced them to live as internally displaced persons in Baku in presumably worse living conditions. In such circumstances, the mere recognition of a violation is not sufficient satisfaction for the moral damage suffered.

As a result, the ECtHR awarded each applicant EUR 5,000 in compensation for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage combined:

79. As follows from the above considerations, the applicants are entitled to compensation for certain pecuniary losses and for non-pecuniary damage. The pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage are, in the Court’s view, closely connected. For the reasons set out above, the damage sustained does not lend itself to precise calculation (see paragraphs 57, 68, 72 and 73). Further difficulties in the assessment derive from the passage of time. As has been acknowledged by the Court (see paragraph 56 above), the time element makes the link between a breach of the Convention and the damage less certain. This consideration is particularly prominent in the present case where, as has already been mentioned, the period over which the Court has jurisdiction ratione temporis started fifteen years ago in April 2002, that is, ten years after the military attack and the applicants’ flight in May 1992, which are the underlying events leading to the applicants’ continuing displacement from their property and homes. An award may still be made, notwithstanding the large number of imponderables involved. For these reasons, the compensation to be awarded to the applicants must be determined at the Court’s discretion, having regard to what it finds equitable.

80. In conclusion, the Court has regard to the respondent State’s primary duty to make reparation for the consequences of a breach of the Convention and underlines once more the responsibility of the two States concerned to find a plausible resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (see paragraphs 48-53 above). Pending a solution on the political level, it considers it appropriate in the present case to award the applicants aggregate sums for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage. Making its assessment on an equitable basis, it awards each of the applicants EUR 5,000 covering all heads of damage, plus any tax that may be chargeable on that amount.

The case of Chiragov and Others v. Armenia shows that even the lack of reliable evidence and documentary proof of the amount of damage suffered is not an insurmountable obstacle to awarding compensation. The approach to the standards of proof should be flexible and take into account the realities in which applicants find themselves (armed conflict, prolonged occupation, the passage of time, etc.).(6)

All of these circumstances make proving the amount of damage significantly more difficult, if not impossible. In such circumstances, demanding standards of proof that would otherwise be fully justified may turn out to be excessive and unfair.

Conclusions

Conclusions

Moral damage is a negative psychological experience endured by a person, consisting of mental pain and anguish. War brings with it an inconceivable amount of such experience. However, not all such experience can be compensated through legal mechanisms.

Firstly, in any legal mechanism, there is a certain threshold of severity of moral damage below which compensation is not provided. For example, the mere fact of the Russian Federation's invasion of Ukraine does not automatically entitle everyone living in Ukraine to claim compensation for moral damages (despite the fact that it is no exaggeration to say that the war has indeed affected everyone).

Secondly, such a "threshold" of compensability is often dependent on the functioning and purpose of a particular compensation mechanism. For example, the UN Compensation Commission did not award compensation for non-pecuniary damage caused by forced displacement or loss of access to property. This can probably be explained by the fact that a fixed amount of compensation was awarded for forced displacement, which in turn was necessitated by the need to promptly review a large number of applications (the Commission received 2.7 million applications). Instead, the ECHR practices awarding significant amounts of compensation for non-pecuniary damage resulting from forced displacement and loss of access to property.

According to the established practice of international institutions, a person claiming compensation for non-pecuniary damage does not have to provide special evidence to prove his or her mental suffering. It is enough for a person to prove the traumatic event (injury, assault, torture, death of a loved one, etc.), and the existence of non-pecuniary damage is deemed to be presumed. Moreover, the standards for proving a traumatic event should be flexible and take into account the realities in which victims find themselves (passage of time, loss of documents due to war and occupation, etc.) The burden of proof, which would be justified in other circumstances, may be excessive in times of war. - With this in mind, international institutions establish special, lowered requirements for proving non-pecuniary damage for victims of war.

Mental pain and anguish should be distinguished from mental disorders, which are equivalent to physical illnesses and as such are subject to separate proof and give a separate right to compensation.

The peculiarity of non-pecuniary damage is that it cannot be accurately calculated. Difficulties in determining the amount of compensation do not deprive the victim of the right to receive it. Nor do these difficulties relieve the court of its obligation to take into account all the circumstances of the case relevant to determining the amount of just satisfaction. The amount of the award should not be taken as a universal measure and an exact monetary equivalent of the experience - the awarded amount only relatively reflects the intensity and duration of the pain and suffering experienced, so that deeper and longer suffering requires more compensation than less deep and shorter suffering. However, the unit of measurement in monetary terms has not been established and depends on many political, economic and practical considerations. In particular, it depends on the characteristics and tasks of the specific body considering the application, the level of welfare and economic conditions in the applicant's country, the capabilities and resources of the responsible entity, etc.

The Institute of Legislative Ideas is an independent think tank that studies the implementation of anti-corruption policy in Ukraine and its compliance with international anti-corruption standards. We analyze the asset recovery mechanism and explore the opportunities for its improvement and extension. Today, we consider it one of the primary tasks to ensure compensation for the damage caused by the Russian aggression against Ukraine at the expense of Russian assets.