>

Analytics>

An overview of alternative instruments for stopping the war and sources of post-war recovery in UkraineAn overview of alternative instruments for stopping the war and sources of post-war recovery in Ukraine

Publisher: think tank “Institute of Legislative Ideas”

Authors: Tetyana Khutor, Andriy Klymosiuk, Taras Ryabchenko, Andriy Mikheev

The publication was issued by the think tank “Institute of Legislative Ideas” within the project “Seizure and Confiscation of Russian Assets” with the support of the EU Anti-Corruption Initiative (AIU), the Think Tank Development Initiative for Ukraine, implemented by the International Renaissance Foundation in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE) with the financial support of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine. The opinions and positions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the AIES, the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, the International Renaissance Foundation and the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE).

Introduction

Confiscation of private assets - WHY?

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a large-scale military aggression on the territory of Ukraine, violating the peremptory norms of international law (jus cogens) that prohibit the unjustified use of force. The Russian invasion was one of the largest since World War II. To achieve its goals, the Russian Federation has deployed several hundred thousand troops, launched more than 3,500 missile strikes on the territory of Ukraine, deliberately destroyed a large number of critical civilian infrastructure facilities, and continues to do so. Most importantly, Russian aggression has claimed a huge number of Ukrainian lives, including civilians. As of October 2, 2022, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights reported 6,114 dead and 9,132 injured civilians. This data only includes officially confirmed cases. Instead, statistics from the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine are impossible to obtain (for example, in the city of Mariupol alone, we are talking about tens of thousands of deaths).

The war launched by Russia is not regional, but global in nature, as it negatively affects the global economy, which has just begun to recover from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Experts predict that Russia's aggression against Ukraine could reduce global GDP by 1% ($1 trillion) by 2023. It is noted that developed economies will suffer more than developing ones, and Europe will be the most affected region, given its trade ties with Russia and dependence on Russian energy resources.

The cynical and brutal nature of Russia's invasion has led to the fact that, despite the rather complicated balance of power in world politics, most countries unanimously condemned Russia as an aggressor, not daring to support or justify its actions. At the very beginning of the war, the vast majority of UN member states (141 out of 193) officially condemned Russia's aggression in Ukraine and voted for a resolution in the UN General Assembly, using the rather rare Uniting for Peace mechanism to bypass the UN Security Council*, where Russia's veto as a permanent member would have made such a recognition impossible.

The world's key powers did not limit themselves to a formal expression of support for Ukraine, but also immediately responded to Russian aggression by imposing economic countermeasures against Russia as a whole and against individual Russian citizens directly involved in the decision-making process to start and wage the war and those who in one way or another supported Russian aggression.

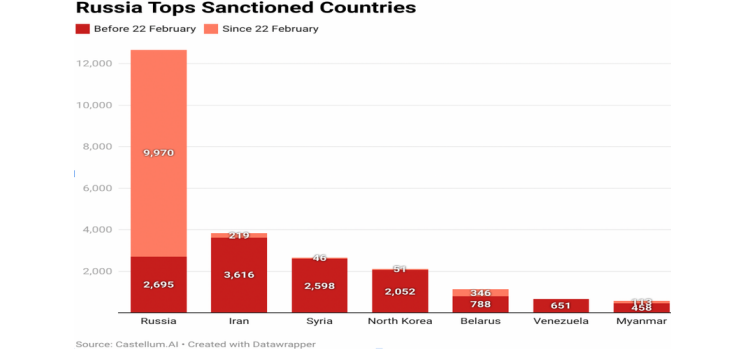

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, the sanctions policy against Russia has become unprecedented. Russia took the first place in terms of sanctions imposed on a single country.

Nevertheless, the experience of the 2014 sanctions imposed on Russia for the annexation of Crimea and the de facto occupation of certain territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine through controlled terrorist groups showed that they failed to stop the Russian military machine and prevent a full-scale war.

The sanctions imposed in 2014 resulted in a 10% drop in Russia's total GDP compared to 2013 (according to the World Bank). However, since 2015, Russia's GDP has been gradually increasing. The Russians themselves, referring to the International Monetary Fund's research, noted that the growth of the national economy (by 2.5% in 2014-2018) significantly exceeded the annual effect of sanctions (0.2%), and the amount of accumulated foreign exchange reserves and unemployment rates improved significantly as of 2019 compared to 2015.

Sanctions imposed after February 24 will be a more painful blow to the Russian economy. As a result of these sanctions, Russia's GDP is expected to fall by 7-8% in 2022 and inflation is expected to rise to 30% by the end of the year. In the long term, the Russian economy is expected to face a deep recession, as well as a significant narrowing of the market and investment, blocking access to technology, and an outflow of valuable human resources.

However, experts note that in the short term, the sanctions will have only a limited impact on Russia's ability to continue the war.

Undoubtedly, the economic impact on Russia from such measures is important and in the long run will make it impossible for it to take aggressive actions against other states. However, Ukraine and its partners cannot wait for the gradual decline of the Russian economy and military potential, while every day Russia attacks the territory of Ukraine, destroys critical infrastructure, causes tens of billions of dollars in damage* and kills Ukrainians.

These measures have significantly intensified the effect of those already applied to the Russian Federation as a state and its individual representatives since 2014, when Russia annexed the territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and occupied certain territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine through Russian-controlled terrorist groups. Nevertheless, although the effect of such international measures by February 24, 2022 was undoubtedly significant, no global result was achieved. The territories of Ukraine continued to be occupied, the state budget revenues of the Russian Federation continued to grow after a period of recession, as did the wealth of Russian oligarchs and politicians. Support for the Russian Federation and its political leadership in parliaments and among political leaders in some European countries was also growing.

Therefore, world leaders are actively looking for tools that can effectively influence the rapid achievement of two main goals:

1) Stopping Russia's full-scale aggression against Ukraine. The importance of achieving this goal is self-explanatory. The effect of the measures taken should be so significant as to influence the political leadership of the Russian Federation and its supporters, forcing them to change their behavior and refuse to continue the aggressive war and support it.

2) Creating a financial basis for Ukraine's post-war reconstruction and compensation for damages. It is clear that the entire financial burden of responsibility for the destruction caused by the war and for the lost lives of Ukrainians must be borne by the aggressor state. The amount of damage caused to Ukraine by this war has already reached hundreds of billions of dollars. As of September 30, 2022, economists estimate that the amount of direct documented losses is over $127 billion. Back in the summer of 2022, the Ukrainian government mentioned the figure of $750 billion needed for Ukraine's full recovery. But it is clear that until the war is over, the amount of damage and this amount will continue to grow.

Given the global practice of warfare, reparations in the form of compensation* were paid after a state's complete defeat in the war, its recognition of international wrongdoing and its voluntary conclusion of an agreement on the payment of such reparations. In the current situation, given the nature of the war, its dynamics, the capabilities and resources available to the Russian Federation and the lack of intention of the international community to directly participate in military operations against the Russian Federation, there is virtually no possibility of the Russian Federation voluntarily paying compensation to Ukraine and Ukrainian citizens. Accordingly, Ukraine and its partners need to look for alternative ways to find sources of compensation, and as soon as possible, in order to begin economic recovery and eliminate the most severe consequences of the destruction caused by Russia.

In addition, an integral part of achieving this goal is full compensation for material and moral damages to relatives and other legal representatives of those killed or injured during the war. So far, Ukrainian taxpayers, as well as allied states that provide Ukraine with significant financial support (almost $20 billion as of early October 2022) and suffer significant losses in this regard, have borne all the costs.

There are several tools that can be used to help achieve these goals. All of them differ in their legal nature and potential ability to achieve results in the near future. We emphasize the importance of each of them. At the same time, following the pragmatic expediency, we will focus on the most relevant instruments for the given context of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

By examining the advantages and disadvantages of each instrument in terms of their potential impact on achieving these goals, we will be able to identify the measure that should be prioritized by Ukraine and its partners in the near future.

Section І

Freezing (blocking) of assets

The asset freeze is one of the types of sanctions imposed by states on the Russian Federation, as well as on individuals responsible for the war and those who support it (Russian politicians, oligarchs, propagandists, etc.). Freezing (blocking) is the temporary imposition of restrictions on the management and disposal of assets, such as selling or re-registering them. Such a measure is intended to influence the behavior of those responsible for the aggression and those who facilitate it, in particular to stop or prevent the commission of new illegal actions, which generally corresponds to the legal nature of sanctions as a preventive measure.

It should be noted that the blocking may apply to both state assets and assets of private individuals.

1) Blocking of sovereign assets of the Russian Federation

Prior to the invasion in 2022, the Central Bank of the Russian Federation had placed significant foreign currency reserves in different countries (8 countries). After the outbreak of war, virtually all of these countries (except China) froze Russia's sovereign assets, totaling about $300 billion. However, in the eight months of the war, no steps have been taken to change Russia's aggressive behavior as a state, even at the risk of losing sovereign assets abroad. It can be assumed that at the outbreak of the war, the Russian leadership was fully aware of the devastating consequences of the aggression for its own economy, including the blocking and possible loss of these assets.

Thus, it can be argued that the impact on stopping the full-scale aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine by blocking the assets of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation abroad is ineffective. Despite the application of these measures, the aggressor's behavior does not change and is unlikely to change in the future.

Since the blocking of assets without their subsequent recovery as a final measure does not provide for the transfer of such assets for restoration and compensation for damage, there is no need to talk about the possibility of influencing the achievement of such a goal.

2) Blocking assets of individuals

This tool has been used in the context of Russia's violations of international law since 2014, when the assets of Russian officials and persons associated with the annexation of Ukrainian territories, including Crimea, were frozen through the imposition of sanctions. On March 17, 2014, the EU imposed sanctions against 21 citizens (including freezing their accounts in the EU) who committed actions related to the violation of Ukraine's territorial integrity. Similar sanctions were imposed by the United States, the United Kingdom and other democratic countries.

After the full-scale invasion of Russia in 2022, the asset freeze was applied more intensively. Thanks to the active communication of Ukrainian government officials and strong political will, states are freezing more and more private assets of Russian politicians, oligarchs, propagandists, and others responsible for the war or actively supporting it.

For example, Belgium has blocked a total of $50.5 billion of private Russian assets, the United Kingdom - $13 billion, Switzerland - $6.8 billion, Germany - $4.67 billion, Poland - $2.7 billion, Italy - $1.7 billion, and France - $1.2 billion.

Thus, it can be said that the instrument of freezing (blocking) private assets is widely used around the world as a response to the influence of these individuals on the conduct of war and its support.

Such a measure has a negative impact on the sanctioned persons whose assets are blocked, making them “toxic” for other counterparties. At present, Russian oligarchs close to the Putin regime (whose assets are most blocked) are looking for ways to lift restrictions on frozen assets, which indicates “inconvenience” for such persons, given the prospect of losing these assets altogether. For example, Roman Abramovich and other oligarchs are trying to challenge the blocking in court and gain access to their airplanes, yachts and real estate. Also, the blocking of assets has significantly revitalized the process of transferring assets to other owners in order to hide such assets.

In this regard, blocking private assets under the threat of losing them can be a potential tool to influence the behavior of individuals who could contribute to ending the war. However, as long as these assets remain in their ownership, blocking alone is not a sufficient incentive to take active steps in this direction.

As in the case of blocking the sovereign assets of the state, there is no question of seizing private assets, so we cannot talk about the possibility of achieving the second goal.

Section ІІ

Civil compensation for damages in individual claims against the Russian Federation

The practice of litigation on claims of private individuals against foreign states for compensation for damage was particularly widespread after the Second World War. Such proceedings are still taking place today. However, the plaintiffs have not been successful in such cases due to the generally accepted principle of immunity of states from the judicial jurisdiction of other states (the principle of jurisdictional immunity). This principle is one of the key principles in customary international law and means that a foreign state is entitled to immunity from judicial proceedings, judgment and its enforcement, including in terms of recovery of property belonging to such state. As of today, there is no universal document that would regulate the limits of application of immunity by such states. The 2004 UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property, which was supposed to fulfill this function, never entered into force due to the lack of ratification by the participating states.

At the regional level, the European Convention on the Immunity of States was adopted back in 1972, to which only eight European countries became parties, so it cannot claim the status of a universal or even influential international act. Accordingly, the principle of jurisdictional immunity of states continues to be an uncodified custom that each state implements in its legislation to the extent it deems necessary. For example, Article 79 of the Law of Ukraine “On Private International Law” stipulates that any measures, ranging from filing a lawsuit to recovery of state property by court decision, are possible only with the consent of its competent authorities. In turn, the Immunities of States Act 1978 of the United Kingdom, although it declares that states generally enjoy immunity from the jurisdiction of the English courts, sets a number of restrictions on the application of such immunity: disputes regarding the state's participation in commercial transactions, participation in the authorized capital of legal entities, disputes regarding the enforcement of arbitral awards, disputes regarding personal injury and damage to property, etc. A similar approach, with a number of peculiarities, is used in the US Foreign Nationals Immunities Act.

In the context of the Russian aggression in Ukraine and approaches to jurisdictional immunities of states at the supranational level, attention should be paid to the position of the International Court of Justice in the case of Jurisdictional Immunities of States: Germany v. Italy (involving Greece), where the ICJ recognized that the sovereign immunities of states cannot be overcome even if such a state violates key norms of international law (jus cogens). It was about numerous war crimes and human rights violations committed by the armed forces of the Third Reich in Italy in 1943-1945. Moreover, the ICJ even recognized that Italy, whose courts ruled on compensation to victims and their relatives at the expense of German property, had committed an internationally wrongful act and was liable to suspension of all claims and restitution (restoration of the state of affairs before the judgments were rendered by completely canceling them). Accordingly, as of today, the approach of refusing to apply judicial coercion to a foreign state dominates international law, despite the gravity of the unlawful acts committed by such a state.

Attention should also be paid to Ukraine's approach to bringing the Russian Federation as a defendant in claims for damages. As already noted, the Law of Ukraine “On Private International Law” establishes the most limited possibilities for bringing another state to justice in a Ukrainian court. Nevertheless, after the full-scale invasion began, the Supreme Court changed its position on the issue of Russian immunity. In April 2022, the court ruled that the Russian Federation does not enjoy immunity with respect to claims of victims of the aggression it unleashed.

The court justified this decision by the territorial tort exception rule, referring to the European Convention on the Immunity of States and the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property. At the same time, according to the researchers, the interpretation of this decision shows that the court was guided rather by the “human rights/jus cogens exception” argument, when the legitimate purpose of applying immunity - “ensuring mutual courtesy and good relations” - is leveled and cannot justify the restriction of the plaintiffs' rights to access to court and to file appropriate lawsuits against the aggressor country.

In the current conditions of war, the approach applied deserves attention and may in the future become the basis for changing the global practice of applying the immunity of a state to act as a defendant in a court of another state.

Despite the possible change in global approaches towards the application of the concept of limited immunity, individual lawsuits against the Russian Federation, which will be filed in the national courts of Ukraine and other states, are unlikely to be an effective method of achieving the set goals.

First, litigation within the framework of civil proceedings will be carried out in a general manner, which may be quite lengthy in time, given the timeframe for possible appeals. Secondly, given that Russia will not enforce foreign court decisions, which has been repeatedly confirmed in practice, realistic expectations can only be placed on the alienation of its property in other countries. As noted above, the blocking of Russian property and the external reserves of its Central Bank has shown a complete lack of influence on the dynamics of the aggressive war. Accordingly, the likelihood that the recovery of Russian property abroad through court decisions will somehow contribute to stopping full-scale aggression is minimal.

There is also a limited opportunity to influence the creation of a financial basis for Ukraine's post-war recovery and compensation for the enormous damage caused by individual lawsuits against Russia. Of course, some of the affected persons or their family members who go to court will likely receive compensation if there is Russian property on the territory of the state that can be recovered for the relevant payments.

Nevertheless, even in this context, it is necessary to understand certain restrictions on obtaining such compensation and the risks of a possible conflict between different legal procedures for blocking or expropriating the property of the aggressor country. As for the recovery of Russian property abroad, the recognition and enforcement of a judgment is also a rather long and complicated procedure and there are no guarantees of success due to different approaches in the national laws of different countries. Nevertheless, it should not be dismissed altogether.

In this document, we do not consider the instrument of compensation for damages in international jurisdictions, due to Russia's failure to fulfill its obligations or selective enforcement of decisions of international courts and arbitrations based on its own political expediency. Thus, until recently, it was possible to compensate for the damage caused by Russia by filing a lawsuit with the ECHR and having the court establish that it had violated the articles of the ECHR. However, after the outbreak of the war and Russia's confrontation with the West, the State Duma passed a law terminating the jurisdiction of this court in the country.

Section ІІІ

Bringing to criminal liability

Another tool to influence the achievement of these goals may be proving a person's guilt in committing a crime in criminal proceedings and passing a sentence against him or her, which should include the imposition of punishment in the form of property liability of the convicted person (confiscation of the property). In this context, we are talking about bringing to criminal responsibility those responsible for the aggressive war, as well as those who actively facilitate and support this aggression.

The relevant legal instruments are contained in both national legislation and the provisions of the statutory documents of international tribunals such as the International Criminal Court, as well as mixed (hybrid) international criminal courts, such as the Special Court for Sierra Leone (Article 19 of the Statute), the Special Court for Kosovo (Articles 22, 44 of the relevant Law), etc.

The actions of the political leaders of the Russian Federation, who directly made decisions on the preparation and outbreak of war on the territory of Ukraine, clearly constitute the crime of aggression, the definition of which is contained in UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 (XXIX), and which was enshrined as a crime in the updated version of the Rome Statute (RS) of the International Criminal Court in 2010 (Article 8 bis).

Article 8 of the RS also sets out in detail the composition of war crimes, which are grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and other established laws and customs of warfare committed daily by the Russian military in the territories temporarily occupied by them (with the complicity, approval or inaction of their military command to stop the crime, which entails joint and several responsibility of the command in accordance with Article 28 of the Statute).

According to the RS, liability for crimes is not limited to imprisonment. Thus, the Statute stipulates that, along with imprisonment, the court may impose a fine or confiscation of income, property and assets obtained directly or indirectly as a result of the crime (Article 77(2)), and may also make a separate order to compensate victims in the form of restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, in accordance with Article 75 of the RS. Accordingly, if a person is convicted by the International Criminal Court or another similar international tribunal, the verdict may also impose material liability in the form of a fine, confiscation of property, and an obligation to compensate victims.

The national criminal legislation of some countries also contains legal instruments to bring perpetrators to property liability for crimes, including those related to aggression, war crimes, and other crimes against global security and international law and order. For example, Article 110 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (CCU) provides for the punishment of confiscation of property for encroachment on the territorial integrity and inviolability of Ukraine, and Article 110-2 of the CCU establishes confiscation of property for financing actions committed with the aim of violent change or overthrow of the constitutional order or seizure of state power, change of the boundaries of the territory or state border of Ukraine.

Nevertheless, although bringing a perpetrator to criminal liability is the means of influence that is most consistent with existing international legal standards in the field of human rights protection, the effectiveness of a criminal conviction in achieving the goals set out here is rather questionable.

Criminal conviction of persons responsible for the unleashing of an aggressive war in Ukraine in the International Criminal Court can only take place if they personally participate in the proceedings (Article 63 of the RS). This is possible only if the accused are detained and brought to the ICC premises in The Hague, which is objectively unlikely until the war is actually over.

As for national courts, even if it is hypothetically possible to detain such persons and bring them to a court of a certain state (in particular, Ukraine), or to conduct a trial in absentia, the likelihood of full enforcement of the sentence in terms of confiscation of property belonging to the convicted person is very low, especially in the territory of other states, as this will face different approaches to the grounds for confiscation of property. Accordingly, the criminal sentence will in no way contribute to stopping the full-scale aggression of the Russian Federation in Ukraine.

In addition, the nature of confiscation by criminal conviction, as provided for by the Rome Statute, the statutes of other international tribunals and courts, and the national laws of most Western partner states of Ukraine, is limited to property and assets obtained directly or indirectly as a result of a crime, and not to all property owned by such a person. Establishing a causal link between a person's property and his or her actions/inactions related to the aggression in Ukraine is already a difficult task, given the strict standards of proof in criminal proceedings. Nevertheless, even if successful, the amount of confiscated assets is unlikely to be sufficient to cover the losses incurred by Ukraine and Ukrainians and to create a financial basis for Ukraine's post-war recovery.

Section ІV

Confiscation of sovereign assets

After the outbreak of aggression and the rapid freezing of Russian sovereign assets by various states, the issue of the possibility of confiscating Russian state assets was logically on the agenda. Canada has made the greatest progress at this stage by adopting a law that establishes the possibility of applying a sanction in the form of confiscation to both state and private property due to the commission by such states and individuals of violations of international law and order and security, gross violations of human rights, etc. At the time of preparation of this document, there are no relevant decisions on the implementation of such measures.

Existing US legislation, namely the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA), the USA Patriot Act of 2001 (UPA), provides the US President with a number of broad powers to prohibit, cancel any transactions, freeze and in certain cases, confiscation of assets of both states and individuals in the event of “any unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States that originates wholly or substantially outside the United States”.

The relevant authority to prohibit any possible property transactions has already been used by President Biden in his April 15, 2021 executive order against the property of the Russian government (which in a broader sense also means any Russian political institutions, including its Central Bank) and the property of persons who are related to the Russian government through joint activities or other contractual relationships. Another example of the successful use of such powers is the executive order of February 11, 2022, to block $7 billion in foreign exchange reserves of the Afghan central bank Da Afghanistan for future assistance to the people of Afghanistan and compensation to victims of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and other terrorist acts. Nevertheless, a key problem with the procedures established by U.S. law is that under IEEPA and relevant provisions of the UPA, the President's express authority to confiscate, and to direct the liquidation, sale, or other disposition of, the property of any foreign state, national, or organization may be exercised provided that the United States of America States “... are engaged in armed hostilities or have been attacked by a foreign power or foreign nationals,” which is hardly applicable to the situation with Russia's armed aggression in Ukraine, where the United States is not officially involved as a party. Accordingly, the United States continues to look for ways to improve and/or simplify the process of confiscation of Russian sovereign assets and, first of all, external reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation placed in the United States.

Other countries (primarily European) that do not occupy such a unique geopolitical position in the world as the United States and Canada and do not have such peculiarities in their legal systems, but in whose territory more Russian sovereign assets are located (France, Germany, etc.), have more difficulties in implementing the mechanism of confiscation of assets of another state solely within the framework of national legislation. Given the problem described above regarding the existence of an international legal custom of immunity of a foreign state and its property from the actions of another state, such countries may face a conflict in the event of the introduction of such a mechanism. For example, the constitutions of many EU member states contain an explicit provision that general rules of international law (including customary law) should be an integral part of national legislation and take precedence over domestic laws (e.g., Article 25 of the Basic Law (Constitution) of Germany). Moreover, as of today, the current principles of the common foreign and security policy at the level of the European Union allow the EU to apply only non-punitive and preventive sanctions under Article 29 of the Treaty on European Union, and frozen funds and economic resources “may not be made available, transferred or sold”.

Accordingly, for the successful implementation of such a mechanism both at the EU level and in each member state, significant legislative changes must be made.

In any case, it is difficult to count on the confiscation of Russia's sovereign assets located abroad as an effective means of influencing the behavior of its leadership to stop full-scale aggression as soon as possible. As we noted above in the section on individual civil lawsuits against Russia in courts, the blocking of its assets placed abroad for a long period of time before the war began could not in any way affect either the fact of Russia's aggressive war or its dynamics. It is highly unlikely that the irrevocable confiscation of these same assets, which Russia has not been operating with and counting on for quite some time, will have any impact in this context.

Nevertheless, in the context of creating a financial basis for Ukraine's post-war recovery, the confiscation of Russia's sovereign assets is a very important and key step, as the total amount of the Central Bank of Russia's assets frozen abroad immediately after the war is estimated at about $300 billion, not including other assets.

Thus, in order to overcome the established sovereign immunity of states and their property and to confiscate Russian state assets without directly contradicting generally recognized international law, the world's states need to introduce a universal approach, establish new practices and attitudes towards the relevant international legal custom. On November 14, 2022, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution recommending the creation of an international mechanism for compensation by the Russian Federation for the damage and losses it has caused. There is still a long way to go to conclude a multilateral international treaty, agree on the mechanism of work of international institutions created specifically for this purpose, etc.

Section V

Confiscation of private assets

As mentioned above, partner states have blocked not only the sovereign assets of the Russian Federation, but also the wealth of politicians, oligarchs, and other individuals responsible for and facilitating the aggression. The total amount of private Russian assets frozen in the world now reaches about $100 billion.

Global trends indicate that world leaders have the political will to further confiscate these assets as a response to the escalation of hostilities and new war crimes committed by the Russian Federation.

For example, at the International Conference on Ukraine's Recovery, held on October 25 in Berlin, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stated that “our goal is not only to freeze but also to use these assets.”

So far, only Ukraine and Canada have been able to realize such intentions and have implemented appropriate mechanisms for confiscation of private assets into national legislation. In Ukraine, assets of a Russian oligarch manufacturer of weapons used to kill Ukrainians were even confiscated. Read more about this decision and the legal framework for such confiscation here.

Other countries are still searching for legal mechanisms to introduce a tool for confiscating private assets of those responsible for aggression and those who facilitate it*. The main obstacle to this process is the need to ensure the legal “purity” of such a procedure and its compliance with the rule of law**. First of all, this refers to the issue of proper protection of private property rights, which is one of the pillars of the legal systems of democratic states.

Indeed, since this mechanism is a significant and irreversible measure of influence, compliance with the requirements of proper interference with private property rights is a crucial aspect that will make such confiscation a lawful and legitimate means. How to comply with the principle of proportionality and make the confiscation process fair and public (taking into account the provisions of the ECHR and the case law of the ECtHR), we have described here.

At the same time, despite the relative legal difficulties of implementing such an instrument, its potential impact on achieving the goals set can be quite effective.

First, this measure is a type of personal liability that can change the behavior of a particular individual. Unlike sovereign assets, it involves the risk of losing one's own wealth, which has been accumulated over the years. Given that the partner states that hold such assets may soon introduce the necessary mechanisms, this risk is quite real. In this context, the behavior of Putin's oligarchs, who are afraid of losing their assets and are willing to take any steps to preserve them, including transferring a significant part of them to Ukraine, is indicative. There is no doubt that some of them do have influence over Putin and can help end the war, not to mention the regime's top politicians, who are also at risk of having their wealth abroad confiscated.

Conсlusion

Conсlusion

Thus, the confiscation of private assets could potentially affect the goal of stopping Russia's full-scale aggression against Ukraine in the short term.

Since we are talking about the possibility of confiscating assets that have already been frozen, as well as those that are still being identified, their amount could reach $100 billion or even more. This amount of money could cover a significant amount of damage caused by Russia. If an effective and transparent procedure for their management and transfer to Ukraine is introduced, such an instrument could create a financial basis for Ukraine's post-war recovery and compensation for the damage caused.