>

Analytics>

Civil society report on Ukraine’s implementation and enforcement of the UN Convention against CorruptionCivil society report on Ukraine’s implementation and enforcement of the UN Convention against Corruption

*This analytics is published in English only

This executive summary of the Institute of Legislative Ideas’ report reviews Ukraine’s implementation and enforcement of Chapters II (Preventive measures) and Chapter V (Asset recovery) of the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). The report is intended as a contribution to the UNCAC peer review process of Ukraine covering Chapter II and Chapter V (Asset Recovery).

Summary

Chapters II (Preventive measures) and Chapter V (Asset recovery)

Most of the work on the report was done in 2021.

To prepare the report we:

- interviewed more than 40 experts (representatives of CSOs and government agencies, civil society councils of government agencies, academics, analysts) knowledgeable about the implementation of the Convention's articles in Ukrainian legislation;

- conducted the large-scale survey, involving more than 100 respondents across Ukraine;

- analyzed 100 reports, studies, and requests for public information;

- examined 30 pieces of legislation.

First due to the COVID-19 pandemic and then due to the war:

- the mandatory submission of declarations was suspended;

- the mandatory submission of reports by political parties was suspended;

- liability for failure to submit information about the ultimate beneficial owners did not apply;

- competitive procedures for civil service positions were simplified;

- public procurement did not follow open procedures for about eight months.

At the end of 2023, Ukraine started to restore its pre-war regulatory framework. Self-declaration and access to the registry, reporting by political parties, etc. are gradually being restored. All of this necessitated updating the information in the report. New statistical data became available, and both positive and negative changes in the implementation of the Convention's provisions occurred.

You may find the detailed information on the progress that has been made in implementing the anti-corruption provisions on the Monitoring Platform for Ukraine's Implementation of the UN Convention against Corruption:

- the Platform is the best example of cooperation between the state and the civil society allowing to present an impartial position on the implementation of anti-corruption policy in Ukraine. Users can see state's and civil society's assessments juxtaposed and can compare them and understand where there are differences and where the positions coincide;

- the Platform is available online for anyone from any sphere of nation's life and contains current information with updates in the areas covered by the UN Convention against Corruption;

- the Platform contains the best and worst practices of implementation of the Convention, which allow to understand where implementation needs to be improved and which practices should be promoted and used as a model for implementation by other countries.

Since the previous evaluation cycle in 2011, Ukraine has adopted several laws, including those aimed at implementing the UNCAC. In particular, the Law on Prevention of Corruption, the Public Procurement Law, the Law on Prevention and Counteraction to Money Laundering were adopted, and the Civil Service Law was updated. The new laws introduced and improved existing mechanisms stipulated by the UNCAC, such as the electronic declaration, public procurement, competition for Civil Service positions, financial monitoring system, etc. Also, during this period, a full-fledged anti-corruption infrastructure was built with an appropriate preventive body (NACP), an investigative body (NABU), a prosecutorial body (SACPO), and a court (HACC).

Description of the Official Review Process

Ukraine's UNCAC review process was scheduled for the fourth year of the second evaluation cycle. At the time of writing this report, the monitoring has not been completed. The second stage of the monitoring process, peer review, is now underway. It is being conducted by international experts from Latvia and Paraguay.

In 2019, Ukraine provided its self-assessment report for analysis and sent it to the UNODC. It was prepared by the preliminary staff of the NACP together with other government agencies. No representatives of civil society or businesses were involved during its preparation. The self-assessment report was not published, but it was made available to us upon request.

The self-assessment report quickly lost its relevance. Most of the information displayed in it is now outdated or inappropriate. With this in mind, NACP has assured our organization that the self-assessment report will be updated in 2021-2022, in cooperation with government agencies and the public, including civil society organizations. Due to the Russian full scale invasion in Ukraine, this deadline was postponed.

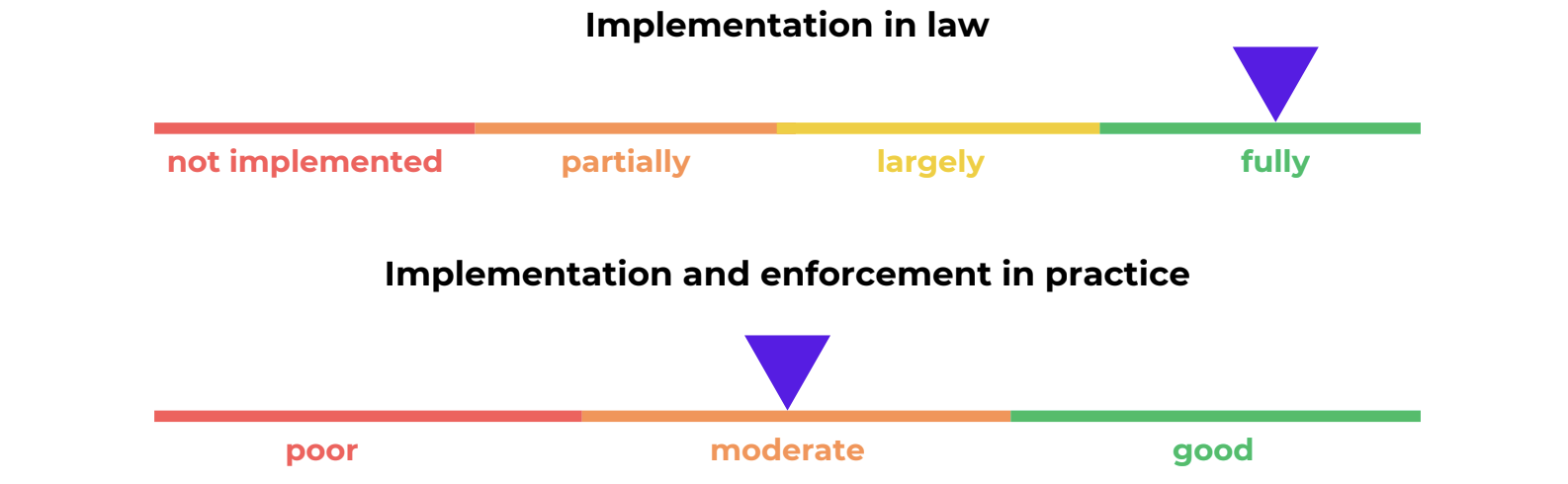

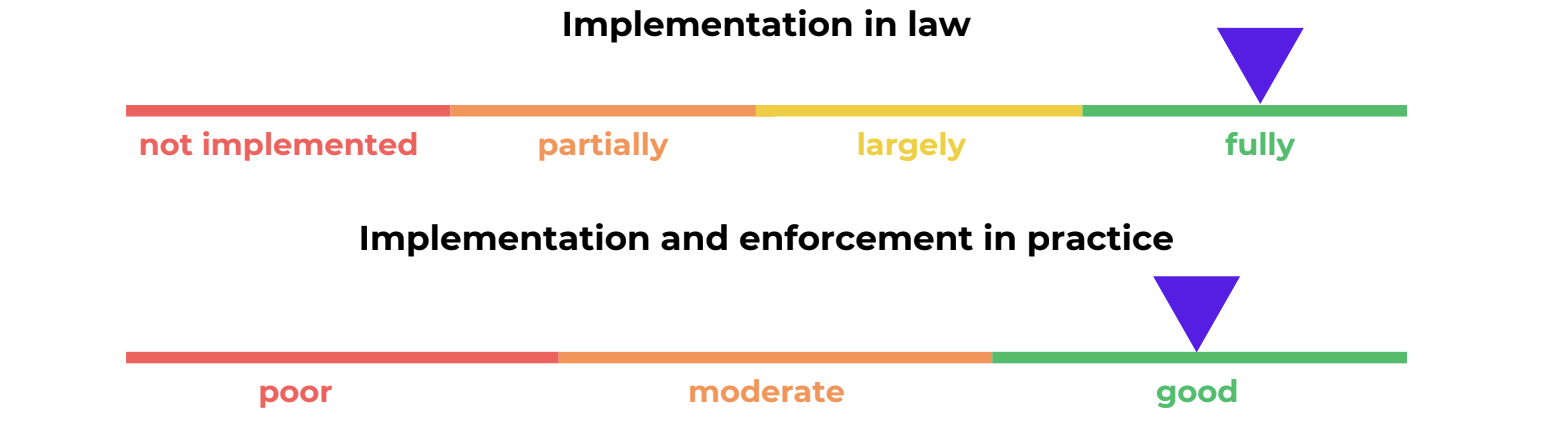

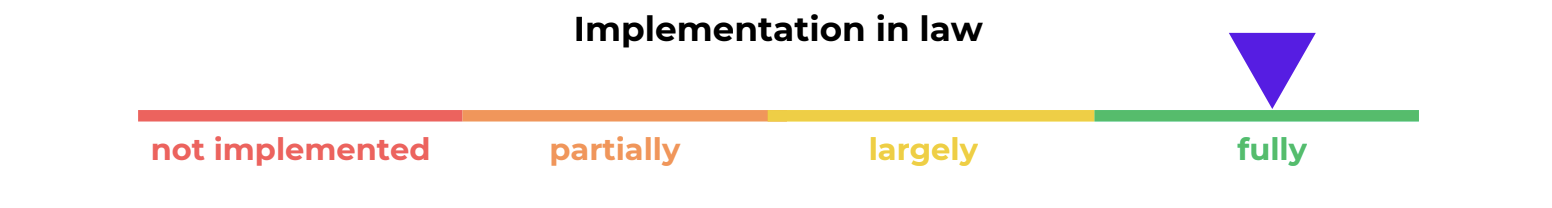

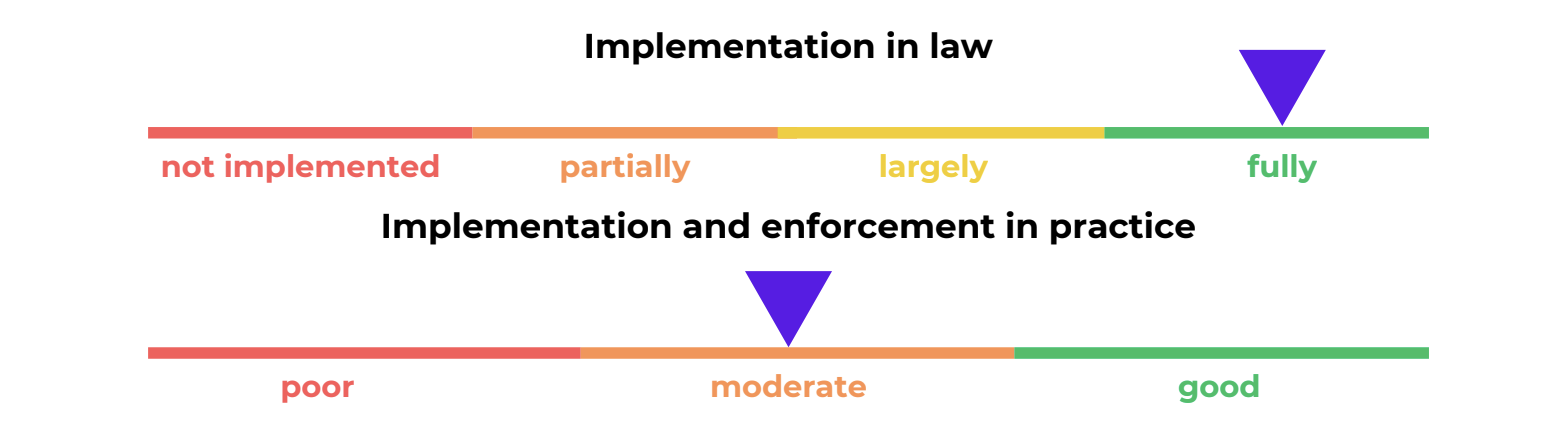

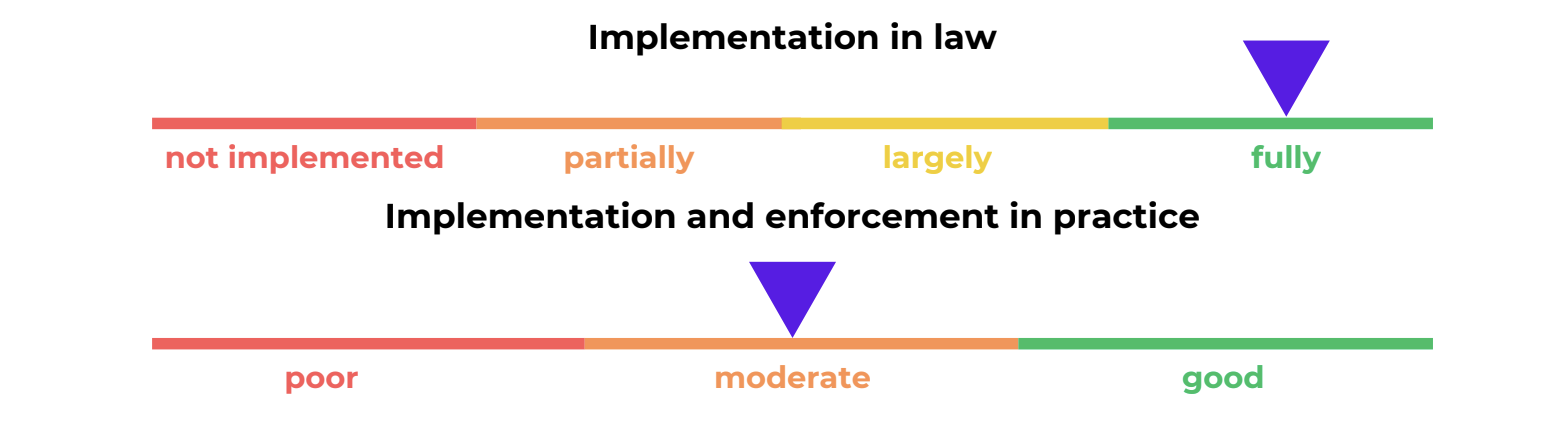

Implementation in Law and in Practice

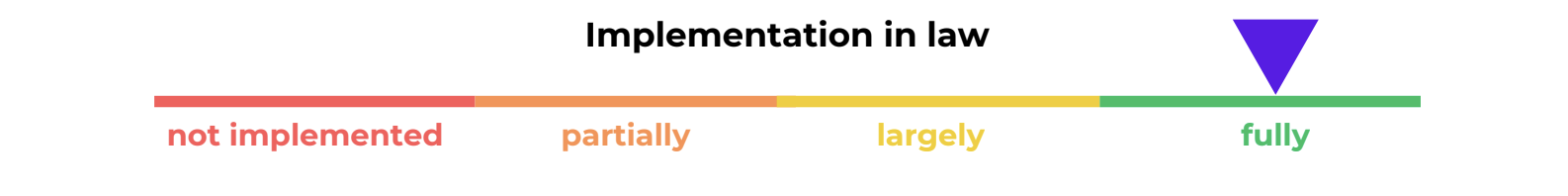

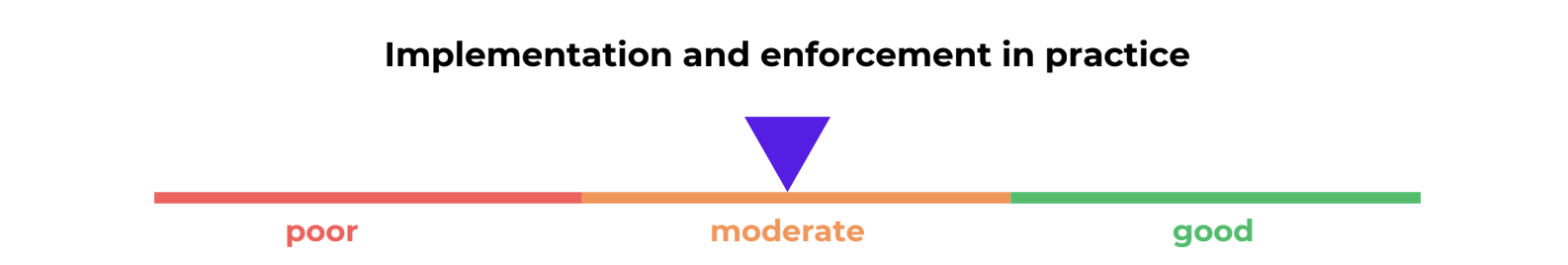

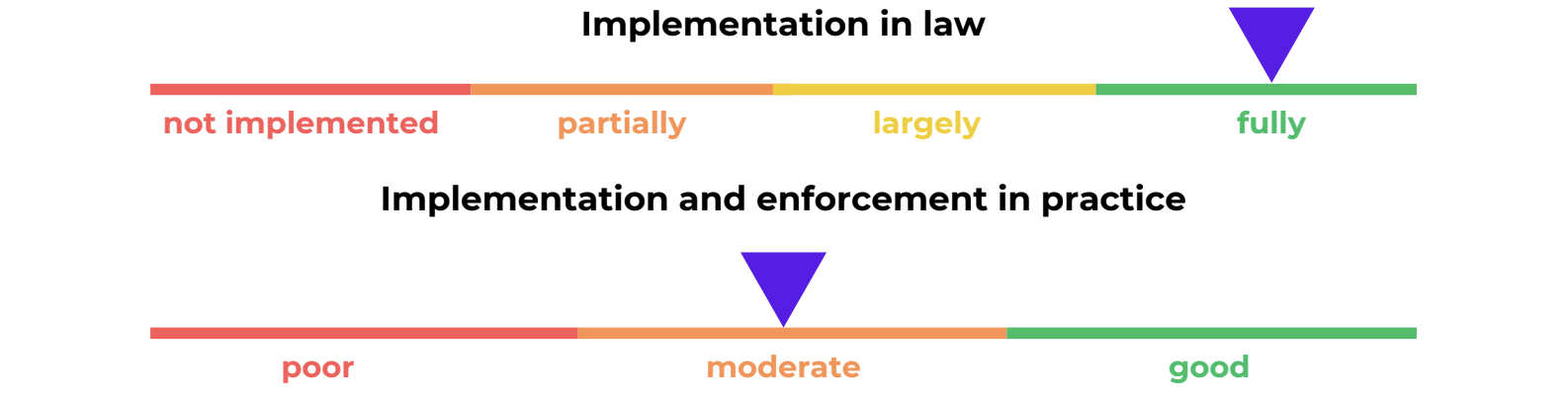

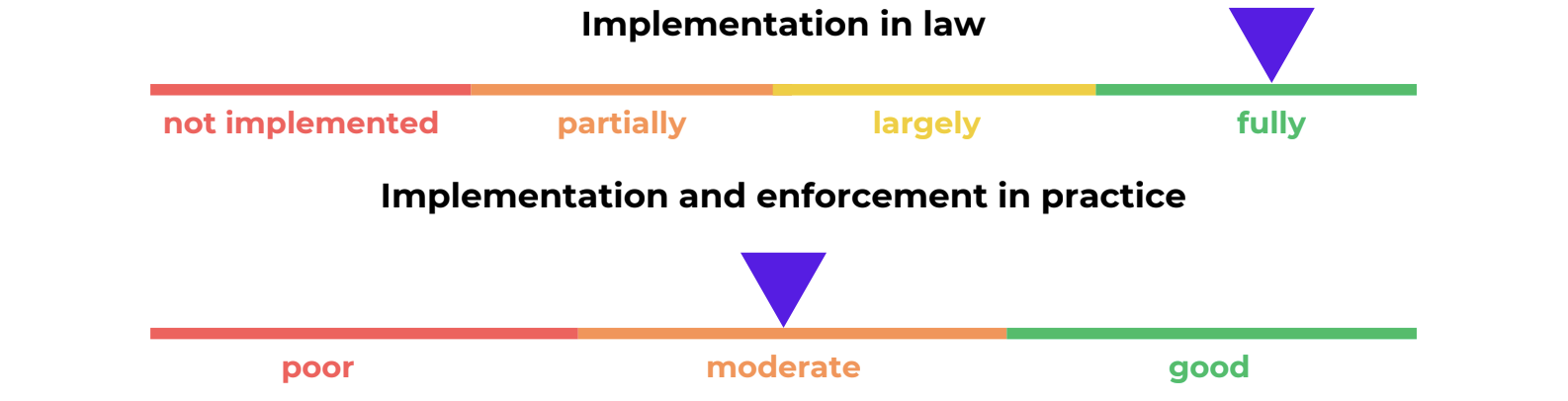

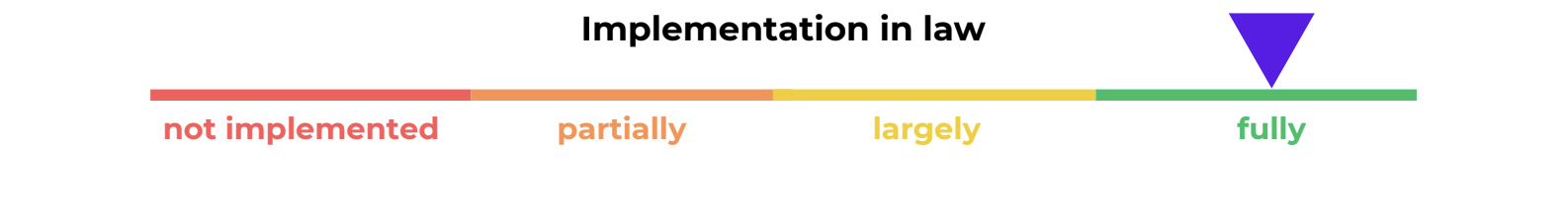

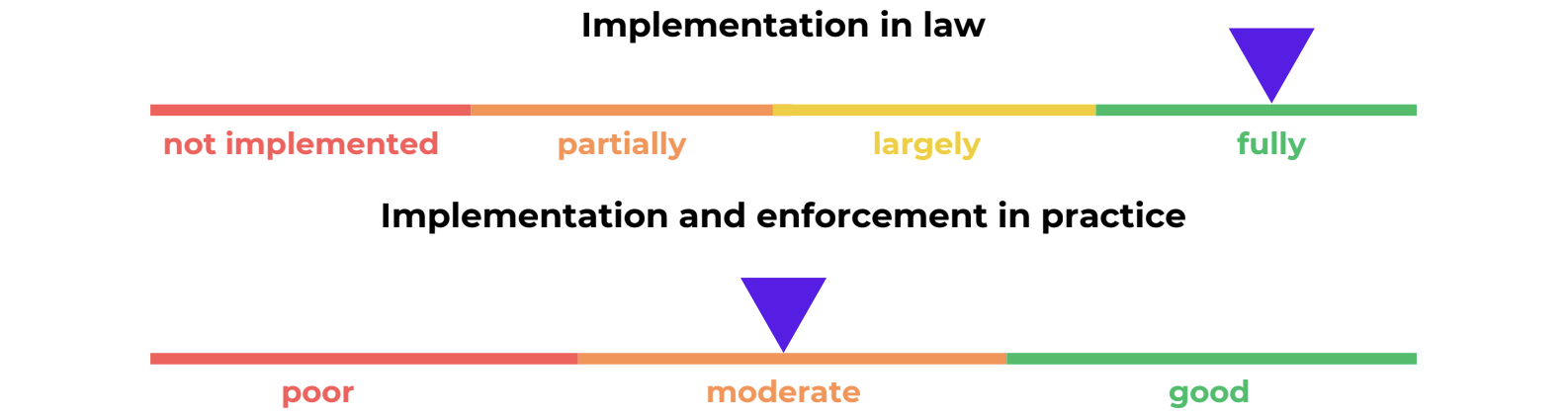

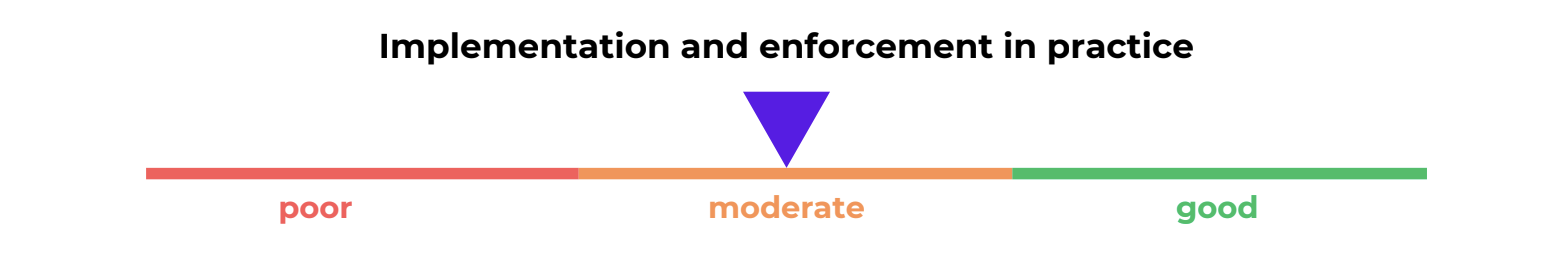

Preventive anti-corruption policies and practices (Article 5) – Ukrainian legislation on the formation and implementation of anti-corruption policies is fully compliant with the UNCAC. However, the enforcement of legal provisions strongly depends on the political will of the decision makers. This affects the approval of the elements of the state's anti-corruption policy and their further implementation in practice. Due to the low level of anti-corruption culture, some anti-corruption practices are perceived formally by the executors. Perhaps the main consequence of these problems is the absence of a strategic anti-corruption document - an anti-corruption strategy from 2018 to 2022. Since its adoption in 2022, a new challenge has been the implementation of the State Anti-Corruption Program. The adoption of the State Anti-Corruption Program followed a broad public discussion. The Program covers a large number of areas of public administration and is aimed at solving important problems in them.

Preventive anti-corruption body or bodies (Article 6) – the preventive anti-corruption body (NACP) has been "re-launched" in 2019. In particular, its organizational structure and management changed. This allowed for a sufficient level of independence of the body. At the same time, the biggest problems are staff shortages and attempts to put pressure on the body by the authorities. The transparency of the NACP and the control over its activities can also be assessed positively. Information on the activities of the body is open to the public and always remains relevant and the public can ensure a sufficient level of control over the activities of the NACP. But certain insignificant problems arise in the implementation of each of these elements of independence.

Public sector (Article 7.1) – national legislation of Ukraine is consistent with the civil service standards enshrined by part one of Article 7 of the UNCAC. However, as in other cases, law enforcement remains low. The absence of competitions during the COVID-19 pandemic and the full-scale invasion of Russia had a negative impact on the civil service. Separate competitions for higher positions were held in violation of the law. A negative aspect of the public service is also the low efficiency of the mechanism for the professional development of civil servants.

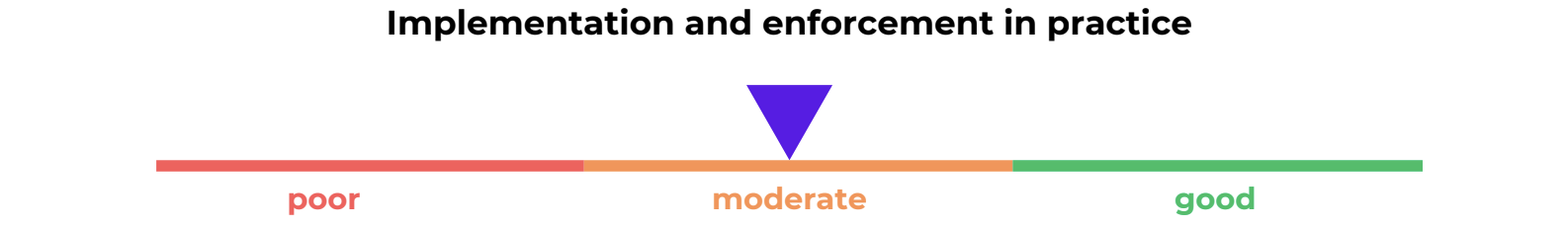

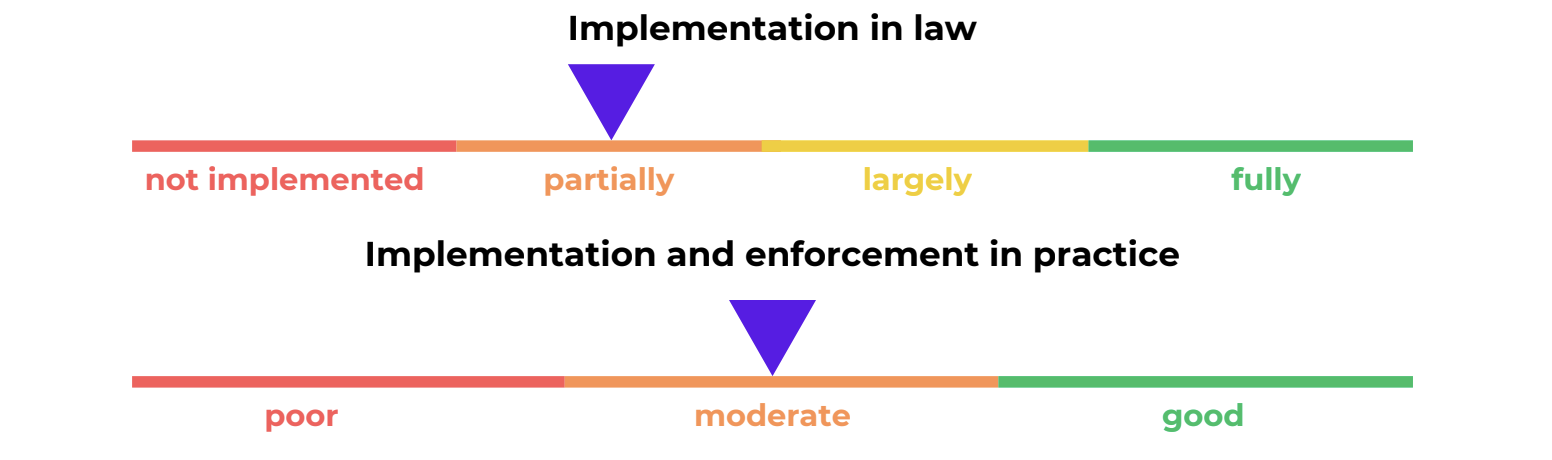

Political Financing (Article 7.3) - national legislation of Ukraine is consistent with the political funding standards enshrined by part 3 of Article 7 of the UN Convention against corruption. Well-grounded limitations on financing political parties and election campaigns, as well as state funding of political parties and their reporting, are defined by law.

At the same time, law requirements are not always fulfilled in a compliant manner. On the one hand, the transparency, openness, and accessibility of party reports can be highly appreciated, which allows the public to exercise effective control over party finances. However, on the other hand, political parties had the right not to submit their reports from 2019 to 2022, first because of COVID-19 and then because of the full-scale invasion. This has deprived the public and the state of control over the financing of political parties and the use of state budget funds. But since 2023, this obligation has been restored.

Funding requirements for political parties and election campaigns can be easily circumvented through a number of schemes. Extremely low efficiency of criminal and administrative liability for violation of political financing law requirements does not ensure bringing law-breakers to justice.

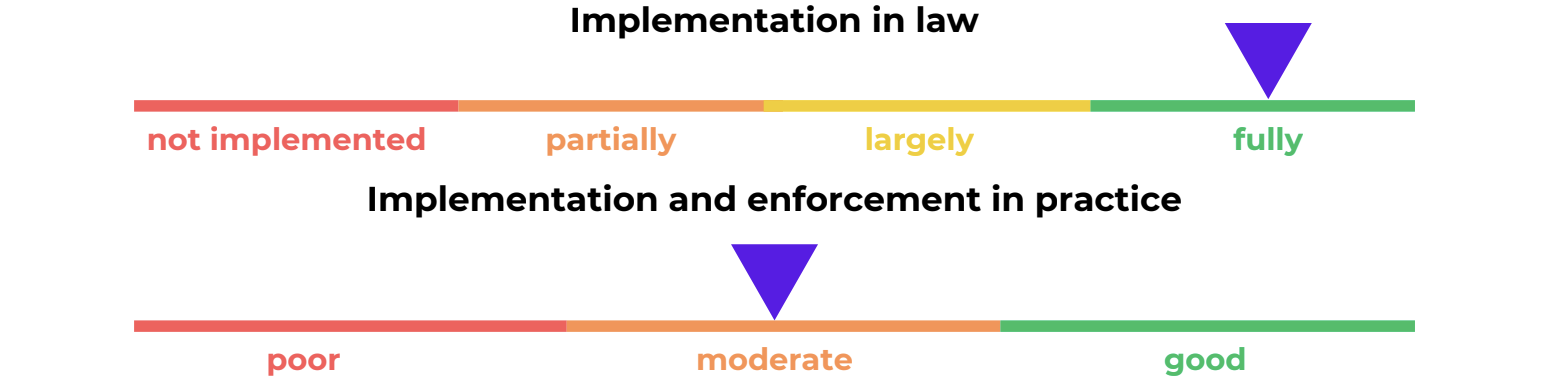

Conflict of interest and declarations of assets and interests (Article 7.4, 8.1, 8.5) - Ukrainian legislation on declaration and conflict of interest is of high quality and meets the requirements of Articles 7 and 8 of the UNCAC. The law establishes a wide range of declarants and assets to be declared, as well as sufficient ways to carry out effective control of declarations. The legislation sets forth sufficient safeguards to prevent conflicts of interest and envisages a variety of measures to eliminate them.

The full scope of declarants, the all-embracing range of assets to be declared, and the availability and openness of declarations give grounds to claim that the declaration system functions properly. However, due to insufficient resources and problems with certain tools, the verification of declarations is not fully effective. The authority responsible for verifying declarations (NACP) conducts verification of declarations well enough, but only with respect to the declarations of high-level officials. Despite the constant improvement of the legislation, there are still ways of hiding assets in declarations. The abolition of the obligation to file electronic declarations following the onset of the full-scale Russian invasion has had a negative impact on state and public control over declaring. In October 2023, the declaration obligation was renewed. The activities of the NACP in identifying and resolving conflicts of interest, and in providing methodological assistance on these issues, should be commended.

Reporting Mechanisms and Whistleblower Protection (Article 8.4 and 13.2) – Ukraine has generally implemented the UNCAC requirements on reporting corruption and whistleblower protection mechanisms in national legislation. However, there is a certain lack of legal regulation regarding specifications for reporting channels, the ways of reporting specific information, and certain guarantees for the protection of whistleblowers.

The legislation is not always successfully enforced. Despite the fact that in practice there are a sufficient number of channels for reporting corruption, insufficient guarantees of anonymity, confidentiality and the possibility to report specific information do not facilitate their active use. Despite the tangible lack of human resources, the work of the body designed to protect whistleblowers (NACP) can be assessed positively. However, the tools available in the NACP to protect whistleblowers are not fully effective, in particular, due to numerous opportunities to avoid liability, the prescriptions of the body are not executed. This practice, together with numerous violations of protection guarantees and occasional legal problems, are significant challenges to the effective protection of whistleblowers of corruption.

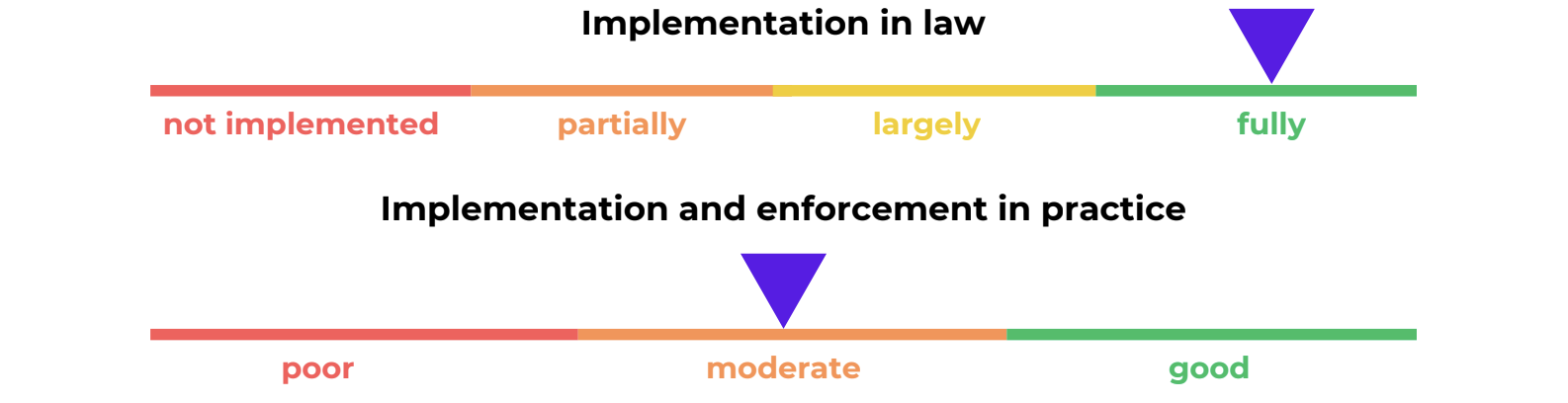

Public Procurement (Article 9.1) – national legislation of Ukraine is consistent with part one of Article 9 of the UNCAC. Enforcement of the law is also at a high level. Public procurements are open and transparent, and information about their conduct is known in advance and is available to all customers. Active application of the Prozorro system, continuous improvement of public procurement procedures, and the effective appeal system to a specialized body (AMCU) allow us to conclude that public procurement is effective in practice.

That is why there are permanent attempts to withdraw certain goods/works/services from the public procurement procedures to reduce the transparency of the use of budgetary funds. Unfortunately, from time to time, such attempts are successful. At present, the ability of the supervisory body (SASU) should be improved because the main control is carried out by the efforts of the public. Another challenge was the non-use of Prozorro procurement at the beginning of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In 2023, there is a gradual return to pre-war procurement procedures. A new challenge is to rebuild destroyed cities. As of September 2023, the amount of damage to Ukraine's infrastructure amounted to $151.2 billion. To ensure the transparency of the reconstruction process, the Dream platform was created, which contains information on financing, management, and control of housing, buildings, and roads reconstruction projects.

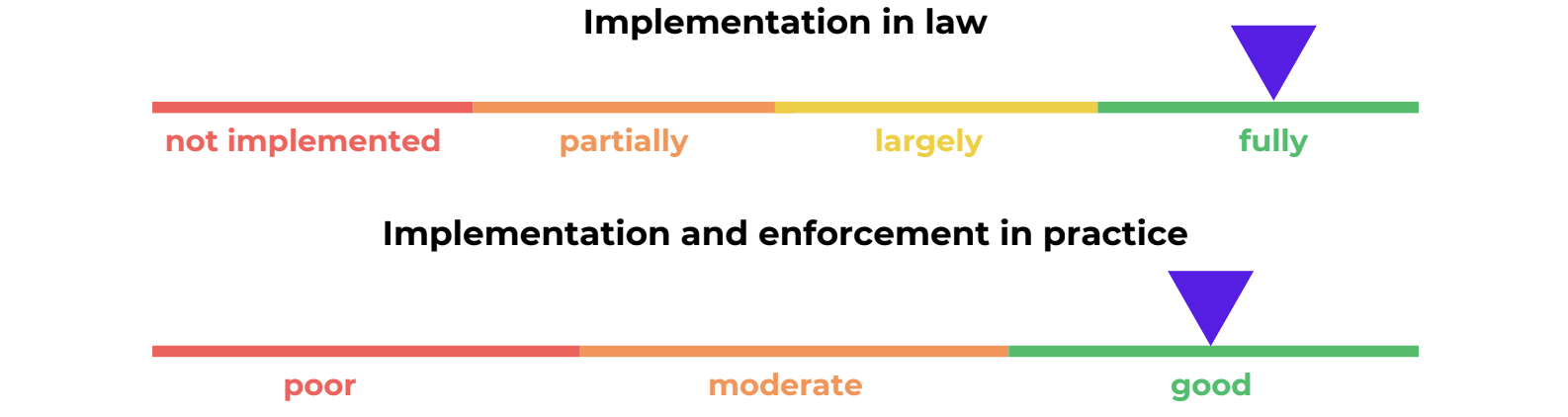

Access to information and participation of society (Article 10 and 13.1) - Ukrainian laws regarding the transparency in the public sector, and participation of individuals and groups outside the public sector to contribute to the public sector decision-making processes are fully compliant with Article 10 and part one Article 13 of the UN Convention against corruption. Necessary legal instruments and mechanisms for the access to public information, with certain restrictions being set forth by law, and the contribution of the public to decision-making processes, are in place. The overriding public interest is the guarantee of access to information. There are institutes of appeal in place. Despite the solid legal framework and recognized advanced information technology tools, there are cases of unjustified non-disclosure or restriction of access to information, and decision-making processes, by the state, especially at the regional level, due to a lack of understanding and commitment to the spirit of the law. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, government agencies have restricted access to information and state registries, which has negatively affected transparency and accessibility of information. The amount of information published by the state in the form of open data is meager for the scale of the public sector of Ukraine.

Despite attacks, threats, and restrictions on anti-corruption activists and journalists, as well as their inadequate protection by law enforcement agencies, civic activism is high. There is a need to strengthen the institutional capacity of the Ombudsman.

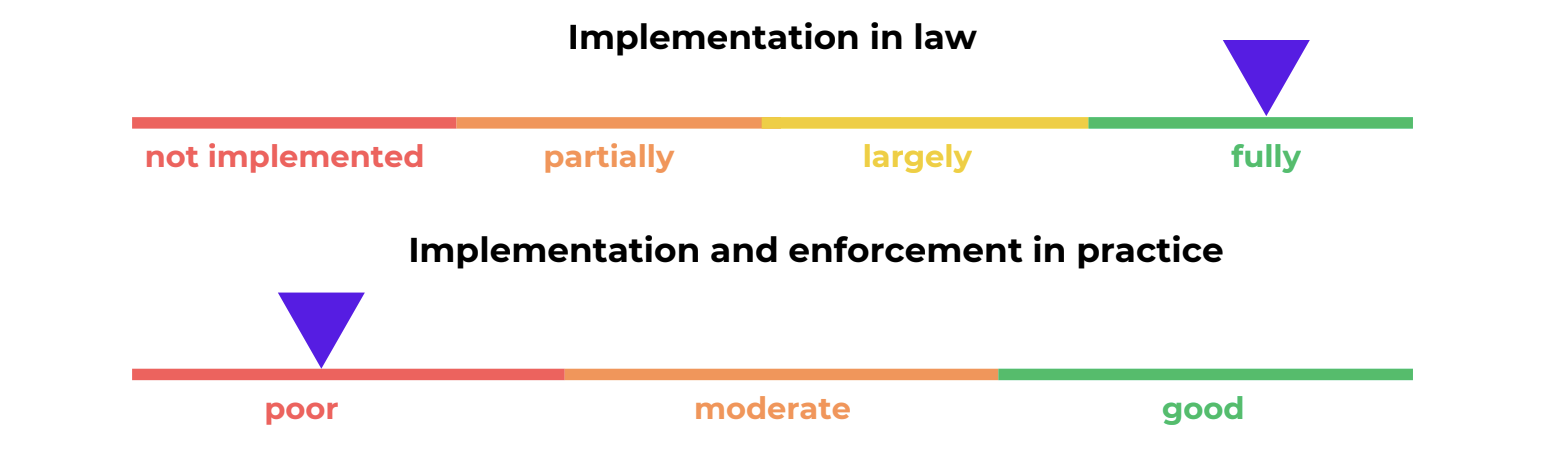

Judiciary (Article 11.1) - Ukrainian legislation on judicial independence and anti-corruption in respect of the judiciary is mostly in compliance with Article 11 of the UN Convention against corruption. However, certain legislative provisions need to be improved, as they grant excessive discretion to the judiciary. Compliance with law requirements is very low. The main reason for this is the dishonesty of individual judges and representatives of the judiciary. The judicial branch of power is constantly at the center of political and corruption scandals. The independence of judges is often violated by judges and judicial representatives themselves. The body that is to ensure the independence and virtue of the judiciary (HCJ) is perceived by the public as biased, corrupt and quite often independently exerts pressure on judges. The positive aspects in this context are the beginning of the HCJ reform, start of work of the HQCJ (High Qualification Commission of Judges) and the creation of a specialized court for handling cases of top corruption (HACC). We should also note the work of the Public Integrity Council, which assists the HQCJ in evaluating current judges and selecting candidates for judicial positions.

Prosecution services (Article 11.2) - Ukrainian legislation on ensuring the independence of prosecutors and combating corruption in the prosecutor’s office is partially compliant with Article 11 of the UN Convention against corruption. The organizational structure of the prosecutor’s office, established by law, does not ensure the independence of prosecutors. The reform of the prosecutor’s office in 2019 has not demonstrated effective results. Once having been dismissed, many prosecutors have resumed their positions. There remains a definite hierarchy in the prosecution services; hence the higher level prosecutors have many ways of influencing the lower level prosecutors. The position of Prosecutor General is overly politicized and controlled due to insufficient safeguards in his or her selection and dismissal.

Private Sector Transparency (Article 12) – National legislation of Ukraine is consistent with Article 12 of the UNCAC. However, its enforcement is not always at an adequate level. In particular, due to the lack of anti-corruption culture, compliance systems develop slowly and have not yet become an effective and popular mechanism of combating corruption in the activities of legal entities. The introduction of the mandatory requirement to disclose information about the ultimate beneficial owners also deserves high marks. Despite the introduction of an open Unified State Register containing information about all legal entities in Ukraine, the information contained therein is not always relevant and reliable. We can positively assess the work of the Business Ombudsman Council as one of the preventive measures against the improper influence of the state on business.

Measures to Prevent Money-Laundering (Article 14) - National legislation of Ukraine is consistent with Article 14 on the prevention of money laundering of the UN Convention against corruption. The financial intelligence unit (SFMS) functions. Necessary tools have been created for prompt response to detected violations in terms of money laundering. The profile legislation was updated, which was positively assessed by MONEYVAL. The activities of the financial intelligence unit in Ukraine (SFMS) and its cooperation with internal and external stakeholders can be highly appreciated. At the same time, the inadequate ability of law enforcement agencies to investigate possible violations identified by SFMS is not conducive to systematic investigation and prosecution of the identified violations.

Anti-Money Laundering (Article 52 and 58) - Ukrainian legislation comprehensively regulates the issue of combating money laundering in accordance with the content of Articles 52 and 58 of the UN Convention against Corruption. Specialized terminology, procedures and regulations have been implemented, and a national FIU has been established.

Financial institutions carry out customer identification and verification in accordance with the law. Problems remain with updating data on ultimate beneficial owners in the national register. There is a ban on dealing with shell banks, and the process of bringing the status of politically exposed persons (PEPs) in line with international standards is ongoing. This should take into account the existing practice in Ukraine. The information exchange between the State Financial Monitoring Service and foreign FIUs is sufficiently established.

Measures for Direct Recovery of Property (Article 53 and 56), Confiscation Tools (Article 54) - Ukraine has provided for the possibility of confiscation of property and assets derived from crime in accordance with UNCAC. The special confiscation and non-conviction-based forfeiture (NCBF) have been introduced. The approach of recognizing and enforcing a foreign judgment and a foreign request for international legal assistance on confiscation issues is being applied.

There is no settled practice of applying special and civil confiscation mechanisms. As of September 2023, the Specialized Anti Corruption Prosecutor's Office (SACPO) has filed 10 lawsuits with the HACC to declare assets unjustified and recover them for the state. We expect an increase in the number of such lawsuits after the resumption of electronic declaration. Foreign court decisions are enforced, but there are not many cases. Ukraine also does not seek enforcement of its decisions abroad. The practice of returning assets confiscated in Ukraine abroad has been absent over the past decade.

International Cooperation for the Purpose of Confiscation (Article 51, 54, 55, 56 and 59) - national legislation on international cooperation is consistent with the requirements of UNCAC. International cooperation in the field of asset recovery is based on reciprocity. It provides for the possibility of sending and executing requests for international legal assistance, concluding multilateral and bilateral international agreements in this area. International cooperation is carried out through the exchange of international requests for legal assistance through authorized bodies. ARMA actively cooperates with foreign countries in asset tracing and participates in international investigations. In the course of cooperation, the parties are mainly guided by the norms of bilateral agreements.

Recommendations for Priority Actions

These recommendations have been submitted to the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, the NACP and other relevant authorities, which we mention in the appropriate sections of the report. These changes will help to improve the implementation of UNCAC

- To implement the provisions of the State Anti-Corruption Programme in the relevant regulatory legal acts (laws and bylaws) of Ukraine.

- Enhance the role of anti-corruption programmes in the activities of state authorities.

- Provide necessary conditions for the formation of territorial offices of the NACP.

- Restore the procedure of full-fledged competitions for civil service positions.

- Adopt the law on the introduction of an administrative procedure for appealing the procedure or results of competitions for civil service positions.

- Eliminate legislative shortcomings that allow bypassing the requirements for financing political parties, and increase the effectiveness of administrative and criminal liability for such violations.

- Increase the capacity of the NACP to conduct asset declarations verification. Apply the provisions of the legislation on the monitoring of lifestyle in practice.

- Expand the capacities of the whistleblower portal and involve all government agencies in its work.

- Abstain from the practice of excluding certain goods/works/services from the scope of the Law of Ukraine "On Public Procurement".

- Enhance the capacity of regulatory authorities to inspect procurement.

- Enhance the protection of the rights of journalists and civil society activists.

- Open state registers and restore access to public information.

- Perform a qualification assessment of judges and fill vacant judicial positions in the judicial system of Ukraine.

- Address the practice of informal influence on judges.

- Ensure the political independence of the Prosecutor General through open competition.

- Enhance the independence of the General Inspectorate of the Prosecutor General's Office.

- Implement provisions on verification of information on the ultimate beneficial owner (“UBO”). Ensure liability for failure to update or enter data on UBOs into the Unified State Register.

- Improve monitoring politically exposed persons (“PEP”) in Ukraine.

The Institute of Legislative Ideas is an independent think tank that studies the implementation of anti-corruption policy in Ukraine and its compliance with international anti-corruption standards. We analyze the asset recovery mechanism and explore the opportunities for its improvement and extension. Today, we consider it one of the primary tasks to ensure compensation for the damage caused by the Russian aggression against Ukraine at the expense of Russian assets.