>

Analytics>

Compensatory function of sanctions: mechanisms for providing restitution to victimsCompensatory function of sanctions: mechanisms for providing restitution to victims

Publisher: Think Tank "Institute of Legislative Ideas".

All rights reserved.

The study is produced by NGO «Institute of legislative ideas» with the support of the Askold and Dir Fund as a part of the the Strong Civil Society of Ukraine - a Driver towards Reforms and Democracy project, implemented by ISAR Ednannia, funded by Norway and Sweden. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of NGO «Institute of legislative ideas» and can in no way be taken to reflect the views the Government of Norway, the Government of Sweden and ISAR Ednannia.

Contents

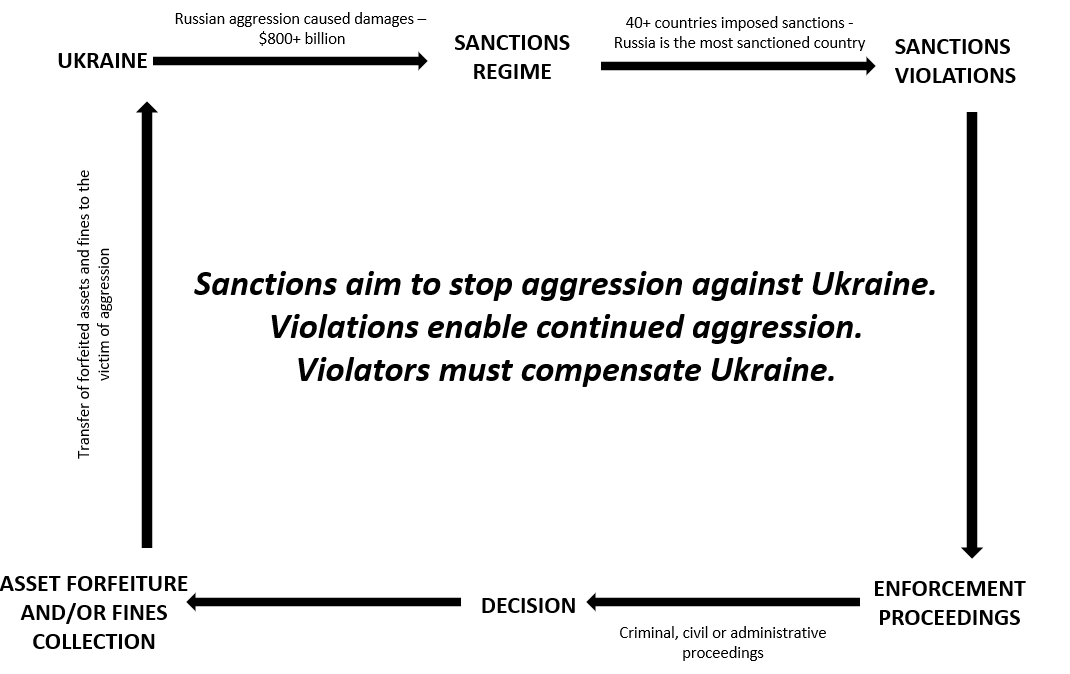

Russian aggression against Ukraine has caused damage amounting to more than $500 billion and hundreds of thousands of casualties. Compensation is left to the affected State and its international partners, which contradicts the fundamental principle of justice that “the one who caused the damage should compensate for it”. The compensatory function of sanctions offers an alternative, transforming the understanding of the sanctions mechanism from solely an instrument of pressure to an instrument of compensation for damages.

The analysis presented highlights two key mechanisms for implementing the compensatory function:

- Transfer of confiscated assets and fines for sanctions violations directly to the affected state. International practice demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. In particular, the US transferred more than $5.4 million in confiscated assets, and Lithuania allocated €167,000 in fines to the rehabilitation of Ukrainian military personnel. In addition, Estonia will spend nearly $500,000 on rebuilding Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

- Confiscation of frozen assets belonging to designated persons to pay compensation to victims. Under this approach, Ukraine has collected more than ₴561 million, more than $236 million, and approximately €440,000 in state revenue. Canada and Estonia have adopted national legislation allowing for the implementation of this mechanism. Moreover, Canada has already started applying it.

The potential of the compensatory function is significant, as thousands of cases of sanctions violations, along with mechanisms for confiscating the frozen assets of designated persons, can generate billions of dollars in compensation for victims.

However, for the compensatory function of sanctions to be effective, coordinated and systemic actions by states are necessary, in particular with regard to:

- Criminalizing sanctions violations, ensuring effective detection and freezing of assets.

- Adopting legislation on the allocation of confiscated assets and fines collected in criminal, civil, and administrative cases to the benefit of victims.

- Reconsidering existing timing, sectoral, and territorial limitations in countries that have already established those mechanisms.

- Developing legal tools to confiscate frozen assets of designated persons to pay compensation to victims, with the right of recourse for reimbursement of incurred costs.

The international community has a unique opportunity to transform its sanctions policy not only by ensuring compensation for victims of Russian aggression, but also by setting a universal precedent of accountability that will serve as a deterrent to future acts of aggression.

Summary

Sanctions are one of the key instruments of modern international politics, the use of which has grown unprecedentedly over the past seven decades. They are imposed on states, organizations, or individuals whose actions pose a threat to international peace, security, human rights, or democratic institutions.

Traditionally, sanctions are attributed with two main functions: coercion and prevention. The first is designed to change the behavior of actors who violate international law, commit acts of aggression, or threaten peace. The second has a deterrent effect, as it demonstrates the negative consequences for those who may commit similar acts in the future.

At the same time, the traditional functions of sanctions do not fully utilize their potential. This is particularly relevant in cases of sanctions imposed in response to armed aggression. Millions of people become victims of such aggression, losing their homes, health, or lives. Recovery and compensation for victims require enormous resources, which usually come from the affected state and its international partners.

However, this approach raises questions of fairness: why should the financial burden of compensation be borne by the affected state or taxpayers in partner countries, rather than those who caused the damage or contributed to the aggression?

Sanctions can contribute to the implementation of the principle of “the perpetrator pays for the damage”. That is why the compensatory function of sanctions is becoming increasingly important – the use of sanctions mechanisms to finance compensation for victims.

There are already examples in international practice of sanctions being used as a compensation tool. For example, the UN Compensation Fund paid out $52.4 billion from Iraqi oil export revenues to compensate for damages caused by the Gulf War. In 2003, Libya agreed to pay $2.7 billion to the families of the victims of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing in exchange for the lifting of UN sanctions. However, these models depended on the resources of the offending state and the effectiveness of pressure from the international community, which limits their replicability. In today's environment, where an aggressor state may have significant resources to resist international pressure and the scale of damage is measured in hundreds of billions of dollars, more flexible and diversified approaches to financing compensation are needed.

The issue of compensation becomes crucial in the context of widespread violations of sanctions legislation. Individuals and companies that circumvent sanctions are effectively contributing to illegal activities and should be held accountable to those affected by them. By analogy, the principle of recovery of criminal assets for the benefit of victims, recognized in international law and enshrined, in particular, in the UN Convention against Corruption, can be applied. It provides for the possibility of transferring confiscated property to the state that has suffered damage, an approach that could serve as a model for compensation in the context of sanctions.

Modern realities require new approaches. The compensatory function of sanctions can be implemented not only through the confiscation or transfer of frozen sovereign assets, which is a difficult political issue, but also through the creation of innovative mechanisms for financing payments to victims.

Consider practical ways to realize the compensatory potential of sanctions in the context of restrictive measures imposed against the Russian Federation in connection with its aggression against Ukraine – the largest war in Europe since World War II. The total amount of damage to Ukraine already exceeds $500 billion, and the number of civilian casualties exceeds 50,000, and these are only those officially included in the UN High Commissioner's report. The real figures reach hundreds of thousands of people. This makes the issue of fair compensation particularly urgent.

This Policy Brief demonstrates the development of sanctions instruments during the period of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The analysis covers the progress made by democratic countries in ensuring that the aggressor is held accountable for its actions. The main focus is on cases of sanctions violations and the transfer of funds to Ukraine, as well as the confiscation of frozen assets of designated persons. The document provides specific recommendations for improving the effectiveness of these instruments and ensuring compensation for damages already now.

Chapter 1

Transfer of confiscated assets and fines for sanctions violations

Despite the significant increase in the scale of sanctions imposed, their effectiveness critically depends on compliance with the established restrictions. That is why the issue of sanctions violations and circumvention has become one of the most pressing in recent years. Recognizing this, the European Union is increasingly focusing on countering sanctions circumvention when adopting new packages. A good example of this is the 19th package of EU sanctions, which is aimed not only at expanding the sanctions lists, but also at closing loopholes.

The scale of the problem of sanctions circumvention is confirmed by the number of criminal proceedings initiated in relation to such facts. For example, almost 2,000 investigations have been launched in Germany, 600 in Latvia, 318 in the United Kingdom, and 275 in Poland.

However, for sanctions to fulfill their compensatory function, it is not so much the investigations that are important as their actual results, namely bringing the offenders to justice with appropriate fines and confiscation of the assets that were the object of the crime. Therefore, the criminal law policy of countries combating sanctions violations is important in this context.

1.1 Criminalization of sanctions violations

It should be noted that criminal liability for sanctions violations is provided for in almost all of Ukraine's partner countries. In the US, legal entities are punishable by a fine of up to $1 million for violating any license, order, provision, or prohibition established by sanctions provisions, while individuals are punishable by imprisonment for up to 20 years. In the United Kingdom and Australia, individuals who violate sanctions legislation face imprisonment for up to 10 years and fines depending on the severity of the violation.

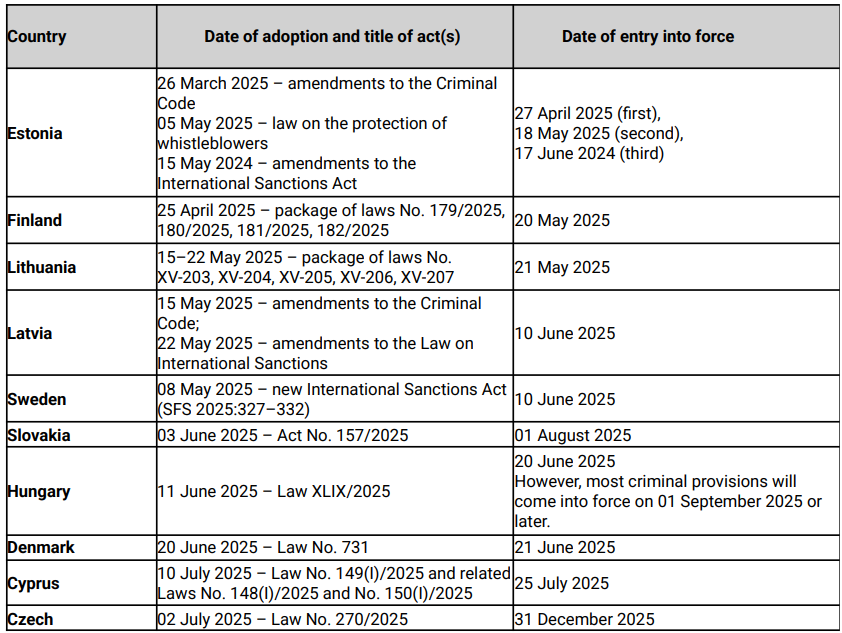

Until recently, the EU had a differentiated approach to regulating the issue of liability for sanctions violations. Such problem has led to significant differences in the definition and scope of the concept of sanctions violations, the types and severity of penalties for committed acts, as well as other compulsory measures applied to violators. That is why, on 24 April 2024, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU exercised their powers to set a minimum standard for regulating liability for sanctions violations by adopting Directive 2024/1226 on the definition of criminal offences and penalties for the violation of Union restrictive measures and amending Directive (EU) 2018/1673.

Despite the 20 May 2025 transposition deadline, as of September 2025, only 10 EU countries have adopted implementing legislation. Some other countries, such as Greece, Spain, Malta, Germany, Poland and Romania have prepared and published implementation drafts, which are currently under discussion. Public discussions and comments on them mostly indicate a positive decision on their adoption.

However, simply establishing criminal liability for sanctions violations will not help victims. To fulfill the compensatory function, mechanisms are needed that would allow the collected funds to be channeled directly to the victims.

1.2 Asset transfer mechanisms

International practice demonstrates the successful implementation of such mechanisms. The US transfers confiscated assets to support victims, while Lithuania has expanded the model to include fines from sanctions violation cases. Let's take a closer look at how these mechanisms work.

The US experience

The US was one of the first countries to adopt legislation allowing sanctions to be used as a compensatory measure in the context of asset forfeiture due to violations. Thanks to an amendment to the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, which came into force on January 5, 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice, through the Attorney General, received powers to transfer to the Secretary of State the proceeds of any forfeited property of designated persons. Subsequently, the US Secretary of State, within the framework of the Foreign Assistance Act (1961), may use these proceeds to provide foreign assistance to Ukraine to “remediate the harms of Russian aggression towards Ukraine”.

It is important to note that this mechanism is already being put into practice. $5.4 million forfeited from Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev, who is subject to sanctions, has been transferred as part of one of the aid packages to Ukraine to support the reintegration and rehabilitation of veterans. In another case, nearly $500,000 confiscated as a result of the uncovering of an illegal procurement network that attempted to import high-precision American-made machine tools used in the defense and nuclear proliferation industries into Russia was transferred to Estonia for its active role in the proceedings. The agreement signed between the Estonian Ministry of Justice and the US Department of Justice directs this amount into rebuilding Ukraine’s energy infrastructure.

However, this framework applies only to assets forfeited before May 1, 2025. This temporal limitation significantly narrows the potential of the mechanism and requires legislative changes to ensure its continued operation.

At the same time, there is no similar mechanism for transferring fines. In this context, it is important to understand that significant funds can be generated from cases of sanctions violations that do not fall under criminal liability but rather qualify as administrative or civil penalties.

In the US the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is responsible for the civil aspect of sanctions enforcement. It monitors compliance with sanctions restrictions and imposes civil penalties in case of violations of the sanctions regime. To this end, OFAC issues regulations that consolidate existing legislation on sanctions restrictions.

OFAC penalties can reach significant amounts. For example, Binance Holdings agreed to pay $968,6 million for over 1,6 million alleged sanctions violations, including transactions totaling $706 million between U.S. persons and users in sanctioned jurisdictions. In another case, Swedbank Latvia agreed to pay $3,4 million for 386 violations involving Crimea-related transactions through U.S. correspondent banks.

The U.S. experience demonstrates the viability of the compensatory function. However, the May 2025 limitation and exclusion of civil penalties, which can reach hundreds of millions, significantly restrict the mechanism’s potential. However, the US is not the only country to apply such a mechanism.

EU experience and Lithuanian example

The EU has adopted Directive 2024/1260, Article 19 of which encourages the establishment of a mechanism for the transfer of confiscated assets related to the violation and circumvention of sanctions.

Some states, such as Lithuania, have gone even further and have already adopted legislative amendments according to which not only confiscated property but also fines for violating sanctions will be used for support related exclusively to the reconstruction and restoration of Ukraine affected by Russian aggression. Moreover, there is already successful practice of applying such provisions. €167,000 from fines imposed on companies for violating EU sanctions against Russia will go to the rehabilitation of Ukrainian veterans.

While Lithuania remains the leader in this regard, ongoing enforcement in other countries demonstrates significant additional potential. For example, for selling 71 luxury cars to Russia in violation of sanctions, resulting in a total amount exceeding €5 million, a German court ruled to confiscate property equivalent to this amount. A Russian bank may have €720 million confiscated due to a possible violation of the ban on the disposal of frozen funds as a result of anti-Russian sanctions. However, without legislative mechanisms like Lithuania's, these assets remain in national budgets rather than supporting Ukraine.

These cases illustrate the substantial financial potential of sanctions enforcement. While currently only a fraction of confiscated assets and fines are redirected to victim compensation (over $6 million has been transferred to support Ukraine), pending cases represent millions in potential transfers. This demonstrates that systematic implementation of asset transfer mechanisms could generate significant resources for victims. Therefore, partner countries should provide for the legal possibility of transferring confiscated property and fines for sanctions violations to victims, not only in criminal cases, but also in administrative or civil cases.

Thus, the transfer of assets seized as a result of sanctions violations seems to be a rather reasonable and fair step. In addition, from a political point of view, establishing the possibility of transferring these funds to victims is entirely justified and does not require any systemic or radical changes in legislation. In most cases, the system of liability and seizure of such assets already exists. It is only important to ensure that they are used for compensation rather than for the state budget.

Chapter 2

Confiscation of frozen assets of designated persons

Along with the mechanism for transferring assets seized for sanctions violations, Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 stimulated the search for new, more radical compensation mechanisms. One such mechanism is the confiscation of frozen assets of designated persons not for the fact of violating sanctions, but for their involvement in or facilitation of aggression.

Traditional sanctions policy involves freezing assets as a means of pressure, rather than confiscating them. However, given the scale of Russia's aggression against Ukraine, which has resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties and hundreds of billions of dollars in damage, sanctions policy must employ more radical measures. This is what has prompted some states to develop new legal instruments.

It is natural that Ukraine, as a victim of Russian aggression, was the first to widely use sanctions as a mechanism for seizing the assets of the aggressor's accomplices located on its territory. Canada and Estonia have developed their own mechanisms for confiscating the frozen assets of designated persons.

2.1 Ukraine's case

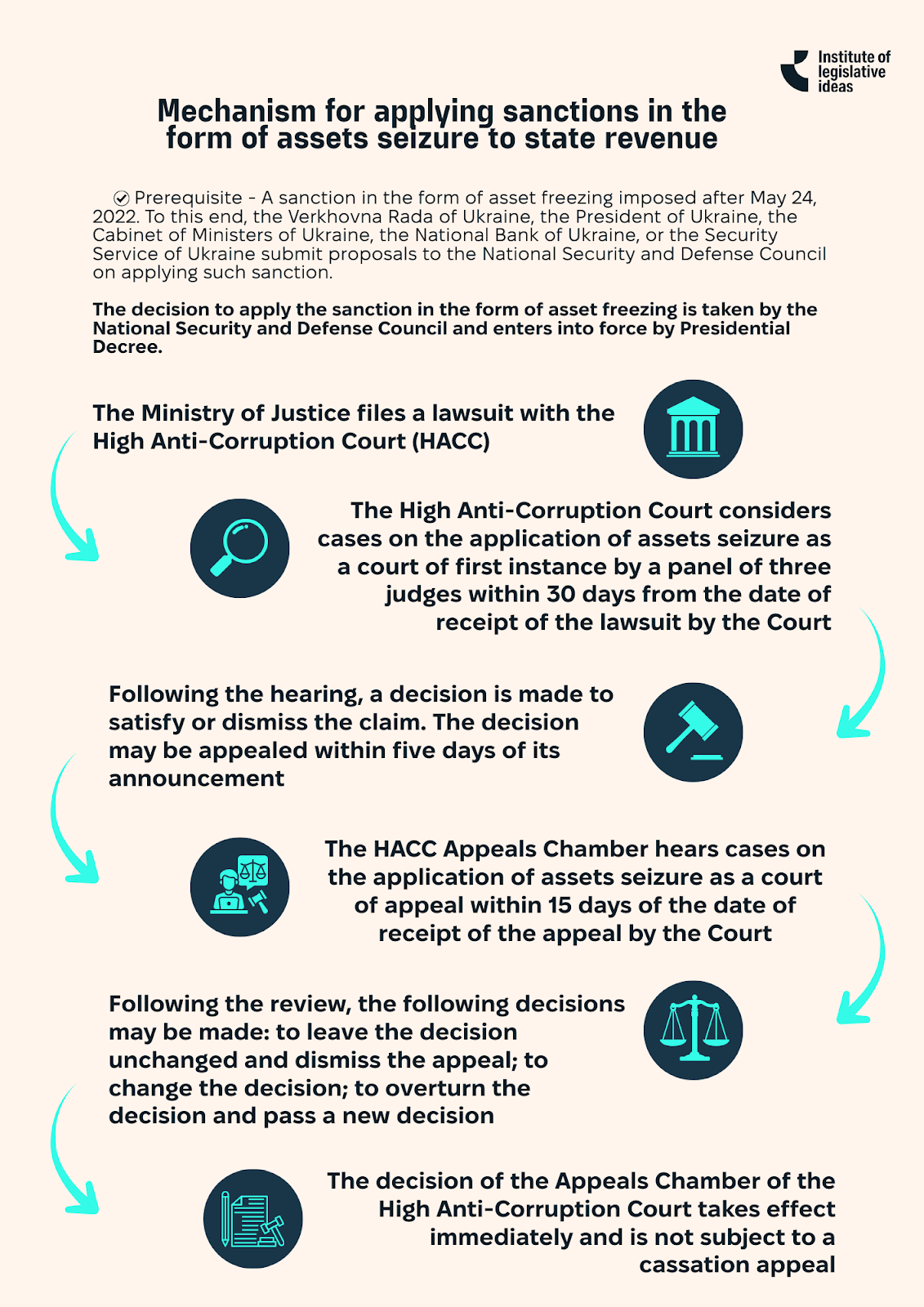

In Ukraine, the possibility of seizing the assets of individuals and companies that are Russia's accomplices in the war against Ukraine was enabled by the adoption of the Law of Ukraine «On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving the Effectiveness of Sanctions Related to the Assets of Individuals» (Law No. 2257-IX), which entered into force on 24 May 2022. This Law introduced a new type of sanction – “asset seizure to the state revenue belonging to an individual or legal entity, as well as assets in respect of which such a person may directly or indirectly (through other individuals or legal entities) perform actions identical in content to the exercise of the right to dispose of them”.

Assets are seized for actions that created a significant threat to the national security, sovereignty, or territorial integrity of Ukraine (including through armed aggression or terrorist activity) or significantly contributed (including through financing) to the commission of such actions by other persons.

The criteria of a significant threat and significant contribution are:

- causing significant damage to the national security, sovereignty or territorial integrity of Ukraine. This category includes 10 clarifying criteria, which generally indicate persons who made decisions about, or participated in armed aggression against Ukraine, as well as collaborators who supported occupation administrations and bodies or held referenda or elections in the occupied territories.

- substantial support of the actions or decision-making specified in the previous paragraph. This is about persons who contributed directly to the invasion and persons who are indirectly involved in the war. Key categories: political and military leadership that facilitated the invasion (e.g., Belarus), big business, large benefactors and donors to state authorities or the military leadership of Russia, buyers of Russian government bonds and propagandists and those who disseminate Russian narratives, among others.

Currently, there is extensive case law on the application of this sanction. The High Anti-Corruption Court has issued more than 70 decisions on asset seizure. Among other things, the High Anti-Corruption Court has collected more than ₴561million, $236 million and €439,000 into the state budget.

Despite procedural guarantees during the court's consideration of cases in this category, including the right of defendants to participate in proceedings, the mechanism is already being challenged in the Constitutional Court of Ukraine as potentially violating the right to property provided for in the Constitution of Ukraine.

Given that this sanction has been in the focus of attention of the Institute of Legislative Ideas since its introduction, ILI conducted a comprehensive study of the compliance of this mechanism with the European Court of Human Rights standards and provided an Amicus Curiae Opinion to the Constitutional Court of Ukraine.

In ILI's opinion, the sanction in the form of asset seizure into state revenue does not violate property rights as:

- such a sanction is provided for by law, which has been duly promulgated, is sufficiently clear and predictable in its application;

- this sanction is a compulsory measure pursuing a legitimate aim – ending the war and restoring the territorial integrity of Ukraine;

- and, finally, the burden imposed on the persons to whom it is applied is justified by the high goal of countering the existential threat posed by the aggressor.

Furthermore, the ILI has published a number of analytical materials on the said sanction in terms of its compatibility with European human rights standards, as well as materials analysing the practice of applying this sanction by the High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine and suggesting ways to improve it.

The Ukrainian asset seizure mechanism has proven effective as a tool for implementing the compensatory function of sanctions. Other countries have chosen alternative approaches.

2.2 Canada's approach

Canada was one of the first of Ukraine's partner countries to adopt legislation allowing the confiscation of assets of designated persons. In particular, there is the Special Economic Measures Act (SEMA), which was significantly strengthened in 2022-2023 specifically to address Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

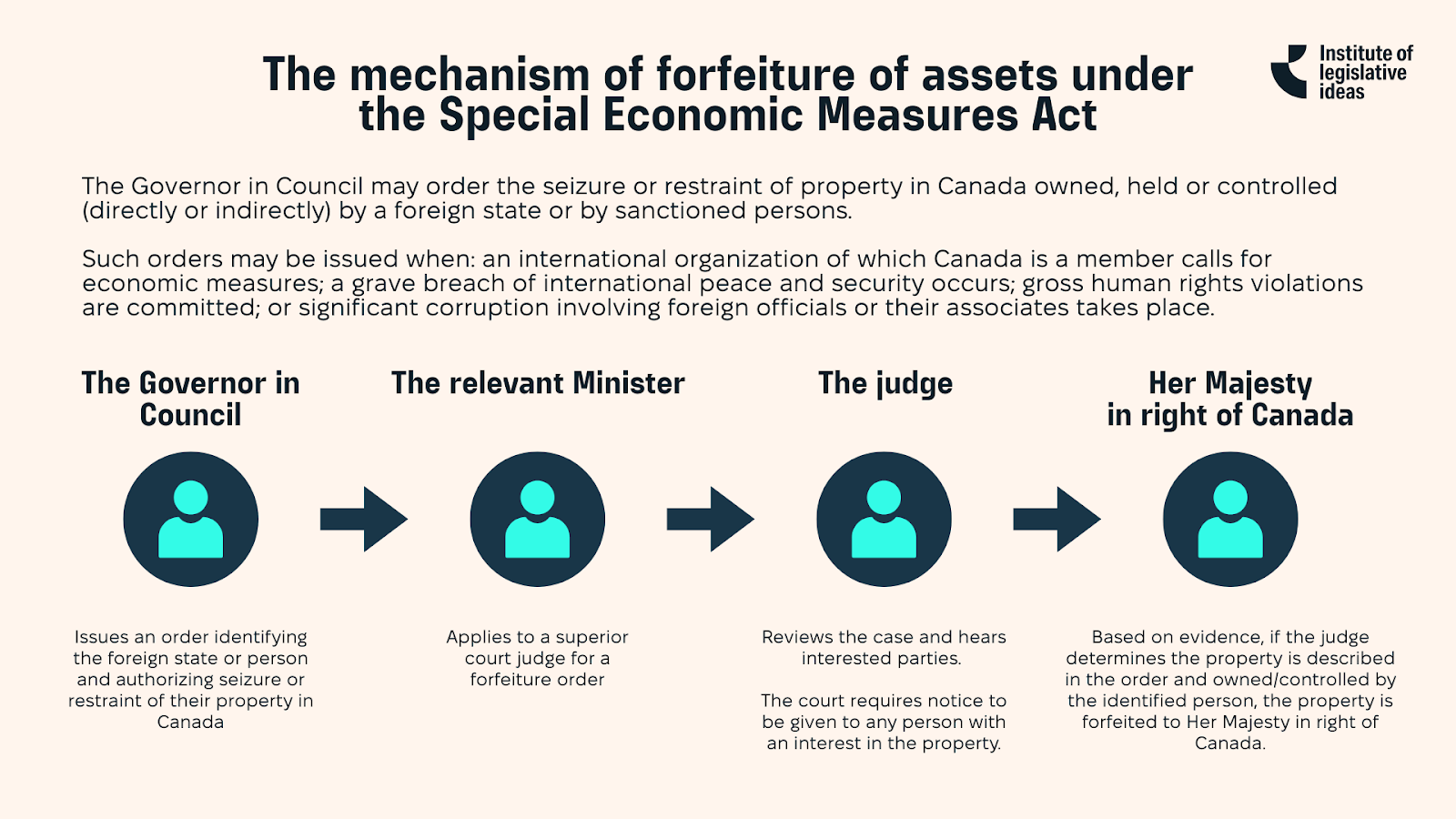

Canadian legislation regulates the confiscation procedure in detail, including the judicial process for considering cases, mandatory notification of interested parties, the right to appeal decisions and exclude property from sanctions, as well as mechanisms for compensation for wrongful confiscation. Any property situated in Canada that is owned, held, or controlled, directly or indirectly, by a foreign state or person against whom economic measures have been taken may be confiscated.

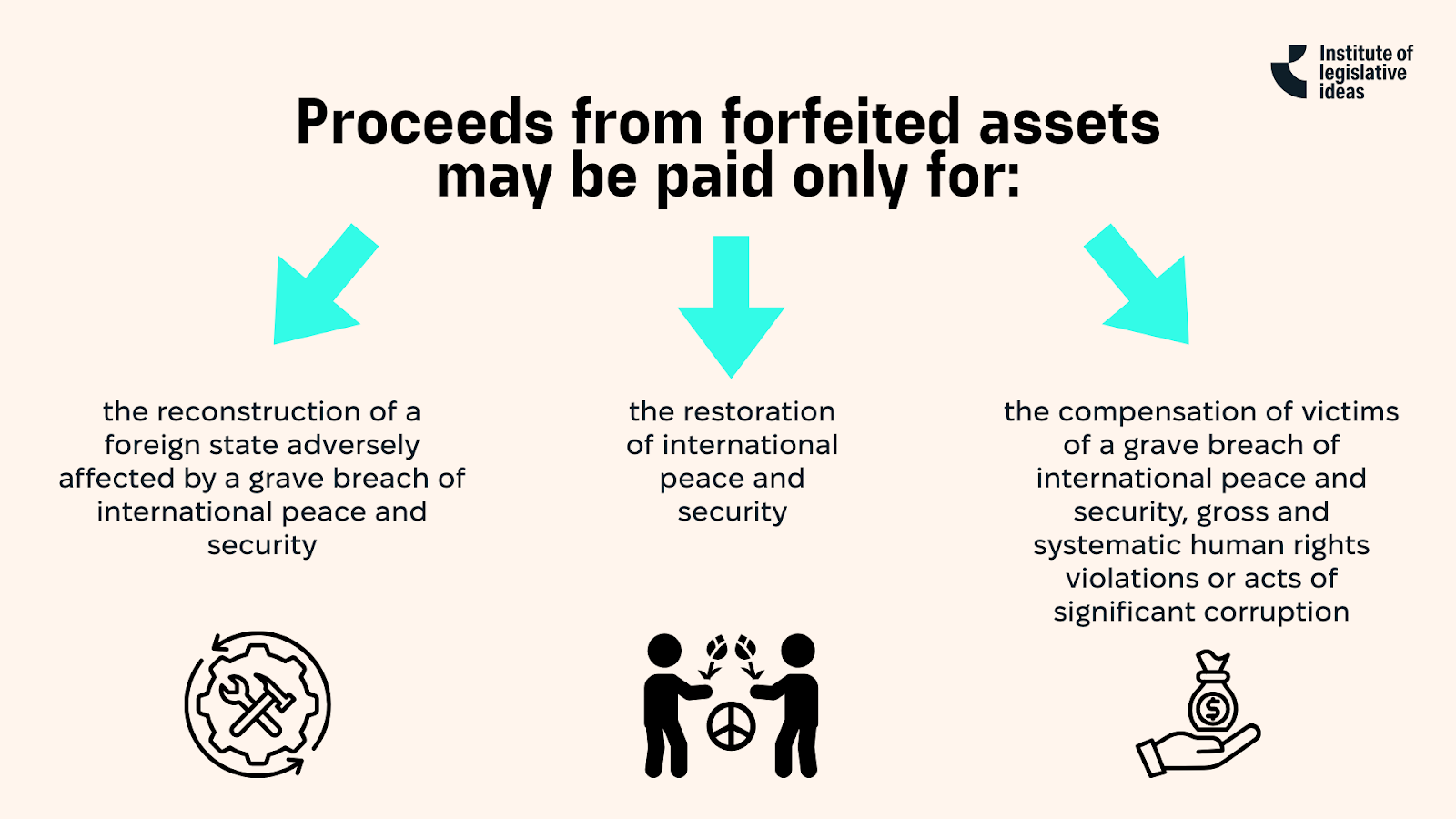

After the property is forfeited, the Minister may, after consulting with the Ministers of Finance and Foreign Affairs, pay amounts not exceeding the net proceeds from the Proceeds Account for the relevant purposes.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs may, with Governor in Council approval, enter agreements with foreign governments respecting their use of proceeds for such purposes.

It is important that the Canadian mechanism is universal – it is not only aimed at supporting Ukraine, but also creates a legal basis for compensating victims of any future aggression.

Steps toward implementation have been taken. In December 2022 Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada announced plans to seize and pursue the forfeiture of $26 million from Granite Capital Holdings Ltd., a company owned by a sanctioned Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich. However, more than two years later, the government has not taken any of the necessary steps. In June 2023 the An-124 Ruslan transport aircraft was seized belonging to the Russian airline Volga-Dnepr, and in May 2025 Canada began the process of confiscation. However, as of early November 2025, Foreign Affairs Minister of Canada said the owners of the aircraft used complex corporate structures that have required significant time to disentangle.

Since February 24, 2022, Canada has effectively frozen approximately $185 million CAD of assets as a result of the prohibitions in the Special Economic Measures (Russia) Regulations. While this represents potential for future forfeitures, the path from freezing to actual forfeiture remains legally and politically complex. Canada’s expropriation without compensation of private Russian assets may run afoul of international law rules on expropriation and of its bilateral investment treaty with Russia.

In particular, Volga-Dnepr filed a $100 million claim, arguing that the Canadian Government’s seizure of the aircraft, implemented pursuant to sanctions against Russia, had negatively impacted its business, and violated the Canada - Russian Federation Bilateral Investment Treaty of 1989, particularly the obligation not to engage in expropriation of Russian-owned assets without prompt, effective and adequate compensation. The results of this case demonstrate the potential of the Canadian mechanism.

2.3 Estonia's approach

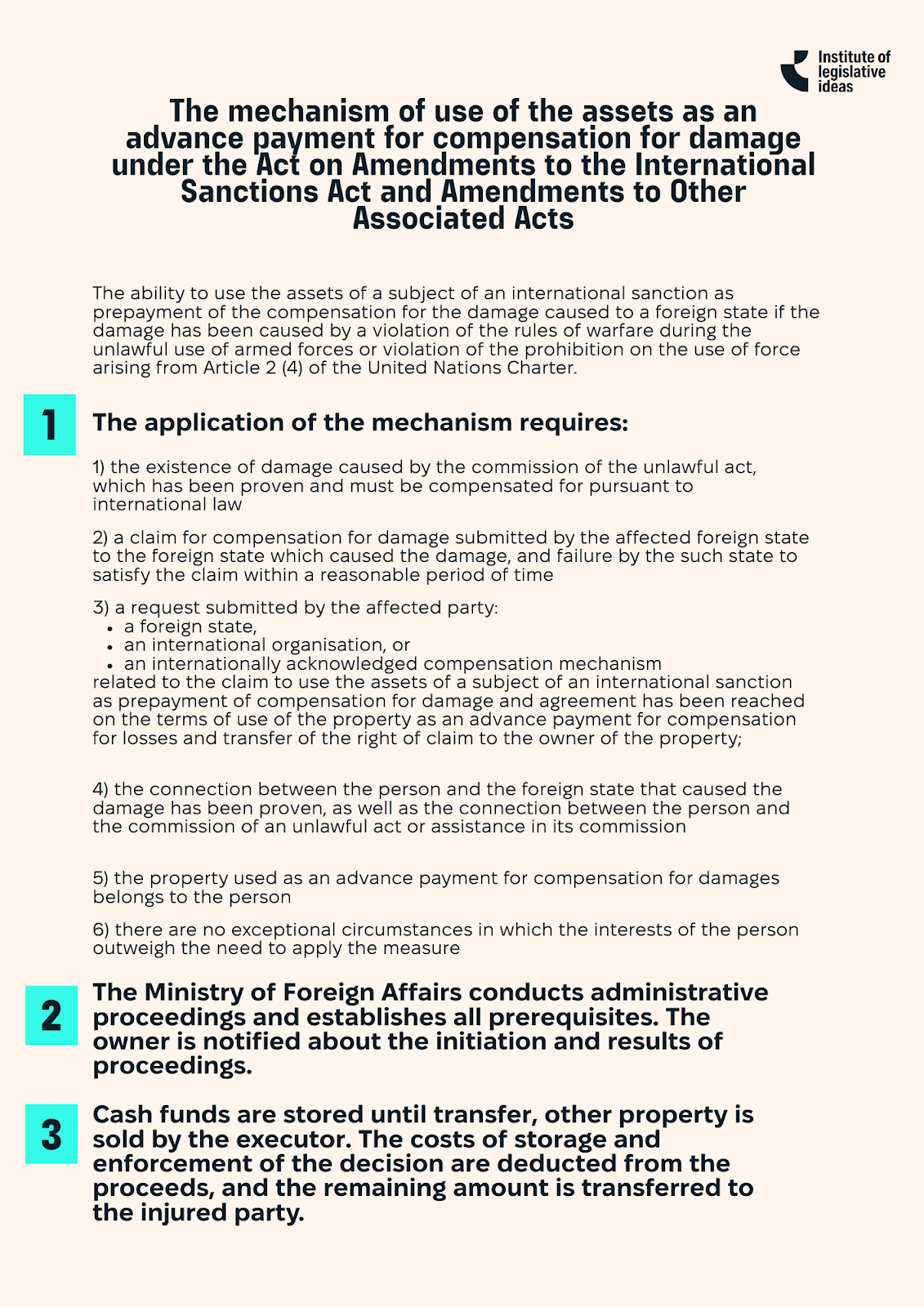

Estonia became the first European country to establish a mechanism for using frozen assets to compensate victims of aggression. In May 2024, the Act on Amendments to the International Sanctions Act and Amendments to Other Associated Acts was adopted by Parliament and signed by the President. However, unlike Canada, it chose a different model for implementing the compensatory function of sanctions.

The Estonian model is based on the use of assets as an advance payment for compensation for damage in the course of administrative proceedings. In cases where a person’s assets are used in advance to compensate for damage caused by a foreign state’s unlawful act, that person receives a freely transferable and inheritable right of claim against the foreign state that caused the damage. In effect, the funds are transferred to Ukraine in advance, and the owner of the assets receives the right to claim compensation from Russia.

Whose assets can be used?

- entity or legal person established in the foreign state that caused damage that is under control of that state or more than 50% owned by that state and that provided financial or material support to the commission of the unlawful act;

- individual or legal person whose connection to the commission of or facilitation of the unlawful act has been established and sufficiently proven.

! A person whose property is subject to an advance payment for compensation for damages may appeal this decision in an administrative court, in which case the decision is suspended for the duration of the court proceedings.

! The owner of the assets acquires a freely transferable and inheritable right of claim against the foreign state that caused the damage for the amount of the value of the property used. The terms and conditions for exercising the right of claim are agreed in an international treaty between Estonia and the injured party.

An important feature of the Estonian model is that it can be initiated not only by the injured state, but also by an international organization or an international compensation mechanism. In the context of Ukraine, this expands the possibilities for applying the mechanism by elements of the compensation scheme, such as the Register of Damage for Ukraine, or those created in the future by the International Claims Commission for Ukraine or the Compensation Fund.

This mechanism demonstrates an alternative approach to the compensatory function of sanctions and sets a precedent for other partner countries of Ukraine.

As of November 2025, there is no information on any steps taken to apply the Estonian mechanism. Nevertheless, in Estonia, Russia's frozen assets amount to approximately €50 million, demonstrating the potential for using the mechanism. Among them, almost €30 million belong to Russian oligarch Andrey Melnichenko. The list also includes another Russian businessman, Vyacheslav Kantor, whose assets are frozen in the amount of almost €5 million.

Conclusions and recommendations

An analysis of international experience in applying the compensatory function of sanctions allows us to formulate recommendations that states can implement to maximize the effectiveness of sanctions mechanisms in compensating victims of aggression:

- Criminalization of sanctions violations by states that have not yet adopted relevant legislation and improving the effectiveness of prosecuting such violations, in particular the identification and freezing of assets that are the subject of the crime. Criminal liability should include both significant prison terms and fines commensurate with the potential gain from the violation. EU member states need to implement the provisions of EU Directive 2024/1226, which will ensure uniform standards and prevent sanctions violations in jurisdictions with weaker law enforcement.

- Adopt legislation that would provide for the allocation of confiscated assets and fines for sanctions violations to the victims of aggression. It is important that such mechanisms cover not only criminal but also civil and administrative cases, as they can generate significant amounts of money. In this context, EU Member States need to implement EU Directive 2024/1260, which encourages the creation of such mechanisms.

- Countries that have already established mechanisms for transferring confiscated assets and penalties for sanctions violations should reconsider existing temporal, sectoral, and territorial limitations. In particular, the US needs to legislate to extend the mechanism for transferring confiscated assets beyond May 1, 2025, and to expand it to cover fines amounting to millions of dollars. It is also important to consider extending the mechanisms to cover future acts of aggression by creating universal legal instruments.

- Adopt legislation that would allow the confiscation of assets of designated persons to pay compensation to victims. Such a mechanism should provide the owners of confiscated assets with the right of recourse for compensation of incurred costs, which reduces the legal risks of expropriation of private property.

The compensatory function of sanctions is a practical tool for ensuring justice. By implementing these mechanisms into legislation, the international community has a unique opportunity not only to support Ukraine, but also to set a precedent of accountability that will serve as a deterrent for future generations and uphold the principle that those who cause harm or contribute to aggression must pay for it.