AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF

*This analytics is published in English only

Publishers: Civil Society Organization “Institute of Legislative Ideas” All rights reserved.

Authors: Tatiana Khutor, Yuri Schwab.

This amicus curiae brief has been provided in accordance with Article 69, part 3 of the Law of Ukraine “On the Constitutional Court of Ukraine.” It has been drafted in the form of counterarguments to the positions of the authors of the constitutional petition set forth in sections II and III. The paragraphs of this brief are numbered according to the numbering in the constitutional petition. For improved legibility of the English version, the following letters have been used to replace the original letters: “А” — “A,” “Б” — “B,” “В” — “С,” “Г” — “D,” “Ґ” — “E.” Part of the opinion is based on separate studies of foreign and Ukrainian scholars with references provided. The opinion contains an unofficial translation of studies. All highlights and underlines of the text are made by the authors of this opinion.

The publication is supported by the Think Tank Development Initiative for Ukraine, implemented by the International Renaissance Foundation in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE) with the financial support of the Swedish Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, the International Renaissance Foundation, or the Open Society Initiative for Europe.

Introduction

Disclaimer

On August 4, 2020, 47 members of the Parliament of Ukraine filed a constitutional petition on the compliance of certain provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” the Criminal Code of Ukraine, the Civil Procedural Code of Ukraine and other relevant laws of Ukraine which affect citizens’ rights and freedoms with the Constitution of Ukraine (constitutionality) No. 04-02/6-3531.

On October 27, 2020, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine issued Decision № 13-r / 2020, in which it declared certain provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention” and the Criminal Code of Ukraine unconstitutional. This decision caused a considerable public uproar, as it abolished certain anti-corruption mechanisms, which resulted in the so-called constitutional crisis emerging in the country.

However, the Constitutional Court has not yet considered some of the issues raised by the MPs in their petition. These include, among others, provisions of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “Illicit enrichment” and the institution of civil forfeiture. Thus, the think tank Institute of Legislative Ideas takes it upon itself to provide its opinion on the constitutionality of the aforementioned anti-corruption mechanisms.

Summary of the Key Points of the Study

1. Provisions on illicit enrichment and civil forfeiture are effective anti-corruption mechanisms. They are in line with the world’s best anti-corruption practices. Provisions on illicit enrichment have already been considered in terms of their compliance with the constitutions in multiple countries. In particular, France, Lithuania, Colombia, Argentina, and the Kyrgyz Republic have all ruled that the illicit enrichment provision is constitutional and does not violate human rights. The previous decision of the Constitutional Court on the compliance of the illicit enrichment provision with the Constitution of Ukraine has led to significant criticism from both the public and Ukraine’s international partners. This decision led to the NABU having to fully close 27 criminal proceedings and close 38 proceedings under part of Art. 368-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. The total amount of assets whose legality of origin was under investigation of NABU detectives in these cases exceeded UAH 500 million.

2. The current version of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “Illicit enrichment” fully complies with the principle of legal certainty. These provisions comprehensively describe the grounds for criminal liability and the consequences of this crime. A person authorized to perform the functions of the state or local self-government as a subject of liability is able to understand the main elements of this article either independently or with the help of lawyers. If necessary, he / she may seek the assistance of the authorized units (officials) for the prevention and detection of corruption operating in his / her institution, and receive advice as provided by law (see items “A”, “B”, “C”of section 2; item “C” of section 3; section 4).

3. The constitutional petition was sent to the Court in the absence of case law on the application of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. To allege a violation of the principle of legal certainty without specific examples in case law is unfounded in view of the case law of the European Court of Human Rights and the recommendations of the Venice Commission. When making a judgment, the Constitutional Court may outline the constitutional framework for the application of illicit enrichment and civil forfeiture. This interpretation would not violate the Constitution of Ukraine and the Ukrainian law; conversely, it would encourage law enforcement agencies and courts to act within the Constitution (see section 2, item “A,” section 3, item “C”).

4. The provisions on illicit enrichment and the institution of civil forfeiture do not violate the principle of the presumption of innocence. As for illicit enrichment, the current version of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine was passed with regard to the remarks of the Constitutional Court set out in its previous judgment. This provision does not in any way imply that an individual is obliged to prove his/ her innocence. On the contrary, it clearly sets out the obligation of the prosecution to prove a number of facts beyond a reasonable doubt. Unlike foreign countries and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, Ukraine does not allow the burden of proof to be shifted to the defense. As for civil forfeiture, it should be noted that it is used in civil proceedings, in which the applicable standard of proof is different. It is unfounded to speak about violating the presumption of innocence in civil proceedings. The authors of the petition frequently interpret the situation at their own discretion contrary to common sense and logic. They often deliberately manipulate the provisions and mislead (see item “D” of section 2 and item “B” of section 3).

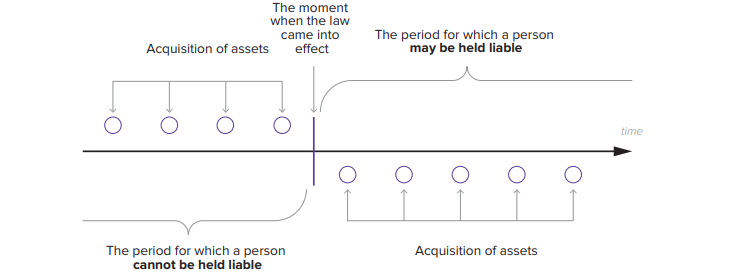

5. Illegal enrichment and civil forfeiture have no retroactive effect. These provisions apply only after their entry into force. Only assets acquired after the entry into force of these provisions may be considered unexplained. Previously acquired assets are not taken into account when deciding whether to prosecute a person. The Criminal Code of Ukraine ties the act of offense to the moment of asset acquisition. The period for consideration of the person’s income is defined by the law and coincides with the period of employment as a civil servant and the periods for which declarations were filed; however, these apply only following the entry into force of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (see items “E,” “B” of section 2, clause “C” of section 3).

6. The current version of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “Illicit enrichment” and the institution of civil forfeiture are compliant with the Constitution of Ukraine (constitutional).

Some of the authors of the Constitutional petition of August 4, 2020

ILLICIT ENRICHMENT

A. GENERAL BASICS OF THE PRINCIPLE OF LEGAL CERTAINTY

The issue of compliance with the principle of legal certainty is raised in almost every part of the constitutional petition. The authors of the petition note that allegedly, Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code overall and its individual provisions are vague, inaccurate, unpredictable, etc. They believe it violates the principle of the rule of law enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine.

At the same time, clause «A» of the constitutional petition does not clearly explain how Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code violates this principle. Instead, general reasoning of this opinion is provided.

It is important that item A of the constitutional petition is based on the reasoning of the CCU judgment No. 1-r/2019 of February 26, 2019. Among other things, the petition almost fully cites seven paragraphs of item 3 of this Judgment.

Among the arguments of the authors of the petition (arguments of the CCU in the Judgment No. 1-r/2019 of 26.02.2019) we can single out the following:

1. “One of the main elements of the principle of the rule of law enshrined in the first part of Article 8 of the Supreme Law of Ukraine is legal certainty. The Constitutional Court of Ukraine stressed the importance of the requirement of certainty, clarity and unambiguity of the legal norm, as otherwise it cannot ensure its uniform application, does not exclude unlimited interpretation in case law and inevitably leads to discretionary decision-making;

2. The European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) in its Report on the Rule of Law No. 512/2009, adopted at its 86th plenary session, held on 25-26 March 2011, stated that one of the necessary elements of the rule of law is legal certainty (paragraph 41); legal certainty requires that legal rules be clear and precise, and aim at ensuring that situations and legal relationships remain foreseeable (paragraph 46);

3. The European Court of Human Rights in its judgment in The Sunday Times v. The United Kingdom No. 1 of 26 April 1979 stated that “a norm cannot be regarded as a ‘law’ unless it is formulated with sufficient precision to enable the citizen to regulate his conduct” (paragraph 49). In its judgment on the case of S.W. v. the United Kingdom of November 22, 1995, the European Court of Human Rights emphasized that an offence must be clearly defined in the law; this requirement is satisfied where the individual can know from the wording of the relevant provision and, if need be, with the assistance of the courts’ interpretation of it, what acts and omissions will make him criminally liable (paragraph 35), etc.

It should be noted that there is no single definition of the term “legal certainty.” Instead, the characteristics of its components can be found in the decisions of the ECtHR (other international courts), national constitutional courts of different countries, the recommendations of the Venice Commission (other international bodies) and in scholarly works.

First, the authors of the petition used the reasoning provided by the Constitutional Court in the judgment on a different version of the “Illicit enrichment” provision. They did not take into account the changes made to the current version of the article, and did not even adapt these arguments to Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code. Secondly, the submission mentions only a few components of legal certainty, but does not indicate other important components. Given this, we consider it necessary to cite them.

The principle of legal certainty stipulates that in the event of problems in the application of the law, the court is obliged to eliminate them by interpreting the provisions of the law. A person must understand the provisions of the law and anticipate its consequences independently or with legal advice.

In particular, in the case of Kafkaris v. Cyprus, the ECtHR stated that:

“the term ‘law’ implies qualitative requirements, including those of accessibility and foreseeability. These qualitative requirements must be satisfied as regards both the definition of an offence and the penalty the offence in question carries An individual must know from the wording of the relevant provision and, if need be, with the assistance of the courts’ interpretation of it what acts and omissions will make him criminally liable and what penalty will be imposed for the act committed and/or omission. Furthermore, a law may still satisfy the requirement of ‘foreseeability’ where the person concerned has to take appropriate legal advice to assess, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences which a given action may entail.”

CCU judge Serhii Holovatyi provided similar reasoning in his separate opinion on Judgment No. 1-r/2019 of 26.02.2019. He noted that:

“1. The accused, if not independently, then with the help of a lawyer, can understand the content of Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, as well as distinguish between “legal” and “illegal” income, identify activities “prohibited by law” and understand what evidence can be used to prove the “legality” or “illegality” of one’s income […]

[…] 3. The principle of the rule of law stipulates that when some legislative ambiguity or contradiction occurs, the main duty of the judiciary is to resolve this ambiguity or contradiction by means of courts interpreting and applying criminal law in a way that would be coherent and foreseeable.”

In the case of Streletz, Kessler and Krenz v. Germany, the ECtHR stated that:

“However clearly drafted a legal provision may be, in any system of law, including criminal law, there is an inevitable element of judicial interpretation. There will always be a need for elucidation of doubtful points and for adaptation to changing circumstances. Indeed, in ... the ... Convention States, the progressive development of the criminal law through judicial law-making is a well entrenched and necessary part of legal tradition. Article 7 of the Convention cannot be read as outlawing the gradual clarification of the rules of criminal liability through judicial interpretation from case to case, provided that the resultant development is consistent with the essence of the offence and could reasonably be foreseen.”

Thus, the law is not required to be drafted in a way that is so clear as to include every possible explanation. The main requirement is for an individual to be able to understand when the liability for violation arises and what punishment is stipulated for a certain act. Moreover, it is explained that sometimes, qualified legal aid may be required. It is important that all inaccuracies in the wording are remedied by national courts through a clear and consistent interpretation of a provision.

The aforementioned Report on the Rule of Law No. 512/2009 by the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission), adopted at its 86th plenary session, held on March 25-26, 2011, also contains an annex, “Checklist for evaluating the state of the rule of law in single states.” Subparagraph i) of clause 2 “Legal certainty” contains the following question for evaluating the state of the rule of law: “Is the case-law of the courts coherent?”

When the Constitutional Court of Ukraine was making its Judgment No. 1-r/2019 of 26.02.2019, it could not answer this question. At the time of the judgment, the case law of the national courts did not include a single decision applying Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code.

A similar situation occurred this time. MPs prepared their petition in the absence of case law on the application of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. Article 368-5 was added to the Criminal Code of Ukraine as recently as in October 2019, and Ukrainian courts simply have not had the time to issue a single decision.

Thus, it is too early to claim that Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine or any of its paragraphs violate the principle of legal certainty (with item “A” not specifying which provisions of the article are unclear), since there is no case law on the application of the contested article yet.

Laws inevitably contain elements of uncertainty. When the CCU makes a judgment, it can use the right to interpret the provisions of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

- If issues arise with the application of the law, national courts are obliged to eliminate them through clear and consistent interpretation of its provisions.

- The law meets the criterion of “foreseeability" even when the person concerned can understand its meaning through legal advice or interpretation by the courts.

- However clearly a legal provision is drafted, there is an inevitable element of judicial interpretation.

- Laws are inevitably couched in terms which, to a greater or lesser extent, are vague. This arises from the very nature of laws written by humans.

- The constitutional petition was filed in the absence of case law on the application of these anti-corruption mechanisms.

- Individuals who are subject to liability for illicit enrichment and civil forfeiture are public officials. They must be aware of the increased standards of integrity, as well as of their duties and responsibilities.

- The Constitutional Court of Ukraine may outline the constitutional framework for the application of illicit enrichment and civil forfeiture.

In a separate opinion on the Judgment of the CCU No. 1-r/2019 of February 26, 2019, Judge Ihor Sidenko, among other things, stated that:

«Laws created by people and for people, as a rule, will naturally have multiple interpretations, as opposed to more or less unambiguous physical laws. If the Constitutional Court of Ukraine recognized that gravity is unconstitutional, the interaction of physical bodies would not disappear. The problem of legal certainty is in the nature of laws created by man. They are not absolute; they are an open compromise between people’s wishes and common sense (ratio). In this framework, common sense dictated that this provision be used not for political revenge against enemies with an exemption for friends, but as a way to cleanse Ukraine of the corrupt “elite.”

The ECtHR expressed a similar opinion in the case of “Del Río Prada v. Spain.” The Grand Chamber of the Court noted that:

“many laws are inevitably couched in terms which, to a greater or lesser extent, are vague and whose interpretation and application are questions of practice […]. The role of adjudication vested in the courts is precisely to dissipate such interpretational doubts as remain.»

Thus, further multiple interpretation is enshrined in the very process of lawmaking. This is mainly because laws are formulated in terms that can be more or less understood in different ways. In this context, we should emphasize that, when the CCU makes the judgment on the constitutionality of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code, it can use the right to interpret certain provisions if any contradictions arise. This was, for example, highlighted by CCU judge Vasyl Lemak in his separate opinion on the Judgment of the CCU No. 1-r/2019 of February 26, 2019:

“Having gotten carried away with hypothetical assumptions of problems in the application of Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code, especially on the subject on whom the ‘burden of proof’ rests, the Court did not try not only to confirm or refute such problems empirically, but also to interpret the practice of application of this norm.

It appears that the Court refused to interpret the provisions of Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code based on the idea that ‘interpreting the law’ presumably falls beyond its powers. At the same time, the Court ignored the difference between official interpretation as a type of proceedings (at the initiative of other entities) and interpretation as a component of judgment justification.

I believe, the Court must interpret the law in every case if the latter is an object of the constitutional control and the issue of its constitutionality is considered. To resolve the issue of the constitutionality of a law means to find / not to find constitutional content in it (embodiment of the principles and norms of the Constitution of Ukraine in its content). Considering the experience of foreign constitutional courts, the methods of interpreting the law are that even if a certain provision of the law allows two different interpretations wherein one interpretation is in line with the constitutional principles and the other one is not, this means the absence of grounds for repealing this provision (constitutionally compliant interpretation) (e.g. see the Judgment of the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic of March 26, 1996, PLUS 48/95). The Court ruled the norm unconstitutional without even trying to interpret it […].

[…] If the Court had attempted to interpret the provisions of Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code, it would have had to perceive it as part of a coherent structure, which includes the Constitution of Ukraine, the official constitutional doctrine (previous positions of the Court) and the Criminal Procedural Code. It is impossible to “read” the norm of a special part of the Criminal Code in isolation from the constitutional principles and norms of the Criminal Procedural Code. Without trying to provide an interpretation, the Court in general could not conclude that there was no constitutional content (in particular, the principle of presumption of innocence, the principle of «silence») in the content of the Criminal Code, and therefore declare it unconstitutional.

Thus, when the CCU makes a judgment on the constitutionality of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, it may initiate currently nonexistent case law. This practice would outline the main constitutional aspects of application of the “Illicit enrichment” article and put an end to unfounded regular petitions filed by MPs on the unconstitutionality of this norm. Moreover, it would be a guide for citizens, pre-trial investigation agencies, procedural management agencies, and judges. This, in turn, would allow meeting ECtHR standards and recommendations of the Venice Commission in terms of judicial interpretation of legal norms.

CONCLUSIONS:

1. Provisions of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine meet international quality standards of law, including legal certainty as an element of the rule of law. The article contains five parts of notes that explain some of the terms used in the disposition. In particular, in the note to Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine clearly outlines the following terms: 1. Person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government; 2. Acquisition of assets; 3. Assets; 4. Legal income.

2. An interested individual can understand the following from the content of the article independently or with the help of legal advice: 1. Who is the perpetrator; 2. What actions entail liability; 3. What consequences a violation of this provision of the Criminal Code entails; 4. What the liability occurs, etc.

3. Any legal provision will inevitably contain certain “gaps,” contradictions, inaccuracies. This is due to the fact that legal provisions are phrased through notions, phrases, concepts, which may be interpreted in different ways in any case. The main task of the judiciary is to provide a clear and consistent interpretation of legal provisions, to provide for stable case law. This, in turn, should eventually dispel any doubts about the application of a particular provision. It is unreasonable to talk about the legal uncertainty of the law in the absence of its application and specific examples.

4. When reviewing a constitutional petition, the CCU may outline the constitutional framework for the application of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. Such an “interpretation” of legal provisions would not contradict the Constitution of Ukraine or the laws. Instead, the case law will provide clear guidance to the national courts, citizens, pre-trial investigation agencies and procedural management agencies and help them understand what kind of practical application of the law complies with the Constitutional provisions.

B. DETERMINING THE PERIOD FOR WHICH THE PERSON’S INCOME IS TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT. THE DEFINITION OF “LEGAL INCOME”

The authors of the constitutional petition claim that:

“The use in the disposition of part one of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine of the following legal phrasing: ‘exceeds their official income’ (…) creates legal uncertainty, since it is impossible to define unequivocally for what period the income of a respective individual must be calculated to establish illicit enrichment in their actions. This period may constitute a month, a year, or the entire term of office of the person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government. Thus, it is impossible to establish the method for calculating the amount (value) of the respective assets in the context of presence of elements of illicit enrichment in the actions of the person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government.”

They believe this provision contradicts the principle of legal certainty and does not comply with Article 1, Article 3, part 2, Article 8, parts 1 and 2 of the Constitution of Ukraine.

The interpretation of Article 368-5, part 1 of the Criminal Code provided in item B of the constitutional petition is arbitrary, fails to take into account the context of anti-corruption legislation, and is not consistent with the real situation.

According to the disposition of this article, a perpetrator of this crime can be a person authorized to perform the functions of government or local self-government under Article 3, part 1, clause 1 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention.” The procedure of taking office by such persons, their dismissal and the term of office on the position is established by the Constitution of Ukraine, the Law of Ukraine “On Public Service,” and other special laws. Under the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” the aforementioned persons are subject to asset declaring, i.e. they are obliged to file declarations.

According to Article 45, parts 1 and 2 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” such persons are obliged to file declarations before taking office (for the previous year; the so-called “zero declarations”), annually while in office and after termination of activity connected with performing the functions of government or local self-government.

Thus, persons subject to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine must indicate their legal income, expenditures and other information under Article 46 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention” during the performance of their activity.

It clearly follows from the above provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention” that the period for which the income of the person concerned will be counted to establish the corpus delicti in the form of illicit enrichment is the period of holding the previously explained position.

In this context, two elements will be taken into account:

- savings and income acquired by the person before the start of activity connected with the performance of functions of government or local self-government, i.e. those contained in the so-called “zero declaration”;

- income acquired during performance of functions of government or local self-government, i.e. indicated in the annual declaration.

Only if a person’s acquired assets exceed their legal income and savings by over 6,500 non-taxable minimum incomes of citizens can we speak about a possible violation of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

Similar thoughts are expressed in the study by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development “On the Take: Criminalizing Illicit Enrichment to Fight Corruption”:

Although UNCAC does not specifically recommend a temporal application of illicit enrichment, one may deduce that the reference to “public official” implies that, at minimum, the period of interest coincides with the public official’s performance of his functions. This approach is also adopted in the IACAC and in many national laws. Chile, for example, makes illicit enrichment applicable to a public official “who during his term” receives substantial and unjustified enrichment, thus limiting investigations to public officials who may have been enriched while in office. El Salvador has a similar limitation, specifying that illicit enrichment can only be presumed when the increase in assets occurs “from the date on which the functionary took office to the day he ceased his functions.” Following this approach, prosecutors may use entry into functions as a baseline and assess whether increases in assets were significant in relation to the public official’s lawful earnings during the performance of his or her functions or term of office. The downside of this approach is that, to avoid prosecution, a corrupt official may simply defer receiving a benefit until after leaving office.

In addition, the constitutional petition states that:

“Paragraph 4 of the Note to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine defines the legal income of a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government, and means income lawfully obtained by the individual from legal sources, defined, inter alia, by paragraphs 7 and 8 of Article 46, part 1 of the Law of Ukraine ‘On Corruption Prevention.’ At the same time, this provision does not define and does not provide for unequivocal definition of what sources are understood as legal sources, while reference to Article 46, part 1, paragraphs 7 and 8 of the Law of Ukraine ‘On Corruption Prevention” narrows such sources and maintains the ambiguity of the notion of “legal income.’

In fact, Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code contains a direct explanation of what income may be considered legal. For instance, clause 4 of the Note to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code refers to Article 46, part 1, clauses 7, 8 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” which establishes at least 10 sources of income. Moreover, the phrase “and other income” indicates that the list is not exhaustive, which effectively provides public officials with an opportunity to indicate legal income from any sources at all as long as they are not prohibited by the law.

In this context, it should be emphasized that the Law of Ukraine «On Corruption Prevention» sets certain restrictions on combining public service with other types of activities. However, it follows from Article 25, part 1, clause 1 of this Law that legal income of individuals specified in Article 3, part 1, clause 1 of this Law can also include income obtained from educational, research and creative activities, medical practice, coaching and referee practice in sports.

CONCLUSIONS:

1. The authors of the constitutional petition interpret the provisions of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine in an arbitrary manner and in isolation from the legal context. They do not consider that individuals who can be charged under Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code are obliged to file declarations. Provisions of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code repeatedly refer to the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” as the two are systemically tied. In turn, the aforementioned Law makes it clear what period is taken into account to calculate a public official’s income, assets, and expenditures to establish corpus delicti under the article in question.

2. Note to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine explains what income may be considered legal. In turn, the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention” contains quite a big list of legal sources of income. What is more, the fact that the list of legal sources of income is non-exhaustive provides an opportunity to declare any source of income as long as it is not prohibited by the law.

C. “LEGAL INCOME” OF PUBLIC OFFICIAL’S FAMILY MEMBERS

The authors of the constitutional petition claim that:

«Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine provides for the possibility of punishment of an innocent person, as a person authorized to perform the functions of government or local self-government may be prosecuted having acquired assets whose value exceeds their legal income by over 6,500 nontaxable minimum incomes when such acquisition has taken place only from legal income of their family members.”

As already noted, the note to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code clearly explains: “Legal income of a person means income lawfully obtained by the individual from legal sources, defined, inter alia, by clauses 7 and 8 of Article 46, part 1 of the Law of Ukraine ‘On Corruption Prevention.’”

In turn, Article 46, part 1, clause 7 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention” clearly states: “The declaration must include information on income received by the individual subject to asset declaration or their family members, including income in the form of salary (remuneration) […] gifts, and other income.” This indicates the following: 1) the legal income of family members is equated to the legal income of the individual subject to declaration; 2) the income of family members, on the contrary, is a proper proof of the legality of the assets acquired by the individual subject to declaration and cannot be used by the government as proof of illegality of the assets belonging to the individual subject to declaration; 3) the list of means of legal income of family members is not exhaustive, which significantly narrows the ability of the state to prove the illegality of income from which the assets were acquired by the individual subject to declaration.

Thus, the legal income of family members cannot be used against the individual subject to declaration, as claimed by the authors of the petition; in fact, it rather creates additional opportunities for the individual to expand the list of their legal income (even if the assets were not in fact acquired as part of such income).

These provisions do not in any way imply that a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government will be brought to liability for acquisition of assets which constitute legal income of their family members.

CONCLUSION:

1. The interpretation of the provision of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine by the authors of the petition is erroneous and manipulative. The authors deliberately mislead the readers. The note to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine provides an exhaustive response to the reasoning used in the constitutional petition. It states that the income of family members is considered the legal income of the subject under Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. Accordingly, a person cannot be held liable for assets acquired as legal income, as this directly contradicts Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

D. PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE

- The authors of the petition deliberately distort legislative provisions and interpret them at their own discretion.

- The new article on illicit enrichment was adopted taking into account the remarks of the CCU.

- To bring a person to liability their guilt must be proven “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

- Unlike a number of other countries and the ECtHR, Ukraine leaves the presumption of innocence intact and does not narrow this concept in this category of cases (or in any other category).

The authors of the petition claim that:

“the provision enshrined in Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine on the obligation to prove certain facts of asset acquisition (including facts of asset acquisition on behalf of a person or the option to perform actions directly or indirectly in connection with such assets which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets) creates an obligation to prove the opposite for the person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government, and if this is not proven, the person may be brought to criminal liability.”

Instead, part 2 of the Note to Art. 368-5 clearly states that:

“Acquisition of assets is to be understood as their acquisition as property by a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government, as well as acquisition of assets by another natural or legal person if it has been proved that such acquisition has taken place on behalf of a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government or that the person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government can perform actions directly or indirectly in connection with such assets which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets.”

The use of the words “if it has been proven” in the provision clearly indicates that pre-trial investigation agencies must have convincing evidence that assets acquired on behalf of such a person or assets in connection with which the person can perform actions which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets.

The content of the article does not in any way imply that the burden of proof lies with the accused.

In addition, Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine was adopted with regard to the CCU remarks set out in the Judgment No. 1-r/2019 of 26.02.2019. In contrast to Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code, which contained the phrasing “legality of whose [assets’] acquisition has not been proven by evidence,” the current article does not contain any indication that the accused must prove the legality of his or her income.

Criminal proceedings under this article take place based on the same rules as all the other articles of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, including principles set forth in Arts. 7 and 17 of the Criminal Procedural Code, which clearly state: “No one should be obliged to prove their innocence of a criminal offense and must be acquitted unless the prosecution proves the person’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.” The prosecution must provide the court with convincing evidence of the person’s guilt, while the accused may in turn exercise their right to defense.

Article 17 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine sets the standard of proof «beyond a reasonable doubt» for all cases of criminal prosecution. This standard emphasizes that there must be strong evidence of a person’s guilt. Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine does not contain any indication that this standard may be violated when the person is brought to liability under this article.

In addition, Article 7 of the Criminal Procedural Code establishes the principle of adversarial proceedings and freedom to submit evidence to the court and to prove to the court its persuasiveness, which is set forth as follows: “Criminal proceedings are conducted based on the principle of adversarial proceedings, under which the prosecution and the defense independently defend their legal positions, rights, freedoms, and legal interests by the means provided by this Code.”

In this context, it is important to look at the best global practices. In particular, the amicus curiae brief, prepared at the initiative of the European Union, also examined the issue of violation of the presumption of innocence in the previous version of the “Illicit enrichment” article. In the opinion, the experts indicate the following:

“The ECtHR jurisprudence shows that presumptions of law or fact are acceptable, and they do not result, as such, in a violation of the presumption of innocence guarantees as long as the State remains within reasonable limits, taking into account the importance of what is at stake and maintaining the rights of the defence. The presumption of innocence is, therefore, not absolute and, if the prosecution builds a prima facie case that calls for an explanation, the accused’s silence can be used to draw inferences. The Court’s jurisprudence also indicates that a violation of the presumption of innocence can be established only in a specific case and after analysis of the evidence adduced by the prosecution [...]

[...] In other national jurisdictions, the courts went further and allowed reversing the burden to the defendant once the prosecution built a prima facie case. This means that once the core elements of an offence of illicit enrichment have been proved beyond a reasonable doubt by the prosecution, an evidentiary burden may be imposed on the official to show that his wealth was obtained from legitimate sources. This approach was followed by the U.K. Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in a 1993 appeal from Hong Kong. [...] But before the burden is shifted to the accused, the prosecution needs to prove beyond reasonable doubt the following: the accused’s public servant status, his standard of living during the charge period, his total official emoluments during that period, and that his standard of living could not reasonably, in all the circumstances, have been afforded out of his total official emoluments. The court observed that where corruption is concerned, there was a need — within reason — for special powers of investigation and an explanation requirement. Specific corrupt acts were inherently difficult to detect, let alone proved in the normal way.”

The above opinions also coincide with the views expressed in the above-mentioned study «On the Take: Criminalizing Illicit Enrichment to Fight Corruption.” In this study, experts have also mentioned the following:

The principle of the presumption of innocence does not exclude legislatures from creating criminal offenses containing a presumption by law as long as the principles of rationality (reasonableness) and proportionality are duly respected. [...]

[...] The Court of Appeals in Hong Kong SAR, China, came to [this] 13conclusion in Attorney General v. Hui Kin Hong.” While it accepted that requiring the accused to discharge the burden of proof deviates from the presumption of innocence, it held the following: ‘There are exceptional situations in which it is possible compatibly with human rights to justify a degree of deviation from the normal principle that the prosecution must prove the accused’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt.’ [...]

[...] The effectiveness and correctness of illicit enrichment prosecutions and their compliance with due process should also be considered in the context of the criminal justice system implementing it This includes considerations consistent with Article 2 of the ICCPR and with Article 14 concerning the right to a fair trial. It is only when these measures are fully implemented that an accused can receive a fair trial for illicit enrichment or any other offense.”

Ukrainian scholars have also studied the application of the illicit enrichment provision in other countries. For example, S. Cherniavskyi, LLD, and A. Vozniuk, LLD, have found the following:

“[...] Such a prohibitive criminal provision [illicit enrichment]15 may be effective if the burden of is at least partly shifted to the suspect or the accused. Therefore, it makes sense that scholars have looked into improvement of the application of this criminal law instrument.

For instance, S. Lut proposes to introduce the notion of presumption of guilt of illicit enrichment into legal vocabulary, primarily in situations when an official’s assets highly exceed his/her legal income. The scholar advises to interpret the presumption of guilt as the duty of the public official accused of corruption to prove the legality and legitimacy of the acquired (available) assets and property to the investigation and in court.

This presumption of guilt is partially or fully applied in some foreign countries, where it is used to combat corruption and organized crime. For example, under Article 72 of the Criminal Code of Switzerland, the court shall order the forfeiture of all assets that are subject to the power of disposal of a criminal organisation. In the case of the assets of a person who participates in or supports a criminal organisation (Art. 260ter), it is presumed that the assets are subject to the power of disposal of the organisation until the contrary is proven.” (Swiss Criminal Code, 1937) [...]

[...] Kh. Nuhrokho believes that the burden of proof is shifted primarily to help law enforcement agencies identify assets owned by the suspect which have been derived from crime. At the same time, the shift of such burden of proof does not mean that it rests solely with the suspect or the accused to prove his/her innocence, while the prosecution does not bear the burden of proof in any way.

On the contrary, the main burden of proof should still be borne by the prosecution. It is for the prosecution to establish that the official in question has led a life that has been beyond his or her legal financial capacity or has excessive wealth that does not correspond to his or her official income. At the same time, the suspect should be required to refute this. Thus, the burden of proof in criminal proceedings on illicit enrichment will be placed on the suspect or accused only partially […]

[...] The principle of the presumption of innocence requires the prosecution to bear both the initial burden of proof in criminal proceedings and the convincing or final burden of proof, too. The prosecution must provide evidence of each element of the crime. It is only in exceptional cases that the accused obliged to bear the burden of proof in relation to certain material and / or moral elements of the crime of which he or she is accused. This occurs when the law embodies a refutable form of presumption (evidentiary presumption) in relation to certain material and / or moral elements of the crime which pose a significant threat to the public.

When the burden of proof is partially shifted to the suspect or the accused, this contributes to the establishment of the objective truth in the criminal proceeding and avoidance of bringing innocent people to criminal liability while facilitating bringing to liability those people who have engaged in illicit enrichment.

If a person has acquired assets in a legal manner, he / she will always be able to provide reasoning on the legality of acquisition of such assets. Even if there is some doubt, the rule should be applied that all doubts about an individual’s guilt are to be interpreted in their favor.”

Based on the indicated provisions, we can conclude that some countries, including developed western democraries, as well as the ECtHR, provide for an opportunity to deviate from the principle of presumption of innocence in this category of cases.

Instead, Ukraine has clearly stated that all significant circumstances of such a crime must be proved by the prosecution. What is more, the standard of proof in such cases remains “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

CONCLUSIONS:

1. The authors of the petition use the same reasoning to substantiate the alleged unconstitutionality of Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine as they did to substantiate the unconstitutionality of Art. 368-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. However, it has not been considered that the current article has been adopted with regard to the CCU position in the previous judgment. Provisions that could theoretically contradict the Constitution of Ukraine in terms of violating the presumption of innocence were removed from it. The current article on “illicit enrichment” does not contain any indication that an individual is obliged to prove his/her innocence.

2. The authors of the constitutional petition audaciously distort the content of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. In particular, they claim that the phrasing “if it has been proven,” used in the Note to Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, clause 2, obliges the person suspected of a crime to prove something. They deliberately highlighted this phrasing in bold. However, further content of the Note to this article, clause 2, indicates what needs to be proven. This is primarily the fact of property ownership; the fact of property acquisition on behalf of the public official, the fact of existence of rights that are identical in their content to the right to dispose of assets. Articles 7 and 17 of the Criminal Procedural Code, Article 2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, as well as reasonable thinking and common sense all indicate that such facts must be proven by pre-trial investigation agencies, as opposed to the suspected individual. However, the authors of the constitutional petition try to argue the opposite and thus manipulate the outcome. Moreover, the procedure for pre-trial investigation of a crime under Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine is the same as for other crimes contained in a special part of the Criminal Code. It is established by the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine and must comply with all the principles enshrined in Art. 7 of the Criminal Procedural Code. The prosecution must prove the accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. In turn, the suspect is not required to prove their innocence.

3. Unlike a number of other countries, Ukraine leaves the presumption of innocence intact and does not narrow this concept in this category of cases. That is true even if global practice shows that corruption crimes specifically allow shifting the burden of proof to the defense if the principles of fair trial are maintained.

E. RETROACTIVE EFFECT

The authors of the petition indicate that:

“The disposition of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine allows to apply the provisions of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine to actions committed before the Article came into effect. A person authorized to perform functions of state or local self-government who acquired assets before criminal liability was introduced under Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine could not know that in the future, they would have to explain the difference between them and the income of this individual and thus could not predict criminal liability for such a difference.”

Under Article 4, part 3 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, the time of commission of a criminal offense is establishes at the time when an individual commits an act or omission stipulated by the law on criminal liability. It clearly follows from Article 368-5, part 1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, and part 2 of the Note to this article that the act which entails liability under this article is “acquisition of assets.” Thus, the disposition of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine ties the act of offense to the moment of asset acquisition if such assets exceed the person’s legal income. The CCU reached similar conclusions concerning the retroactive effect of the law in clause 6 of Judgment No. 1-r/2019 of February 26, 2019.

This article does not in any way imply that the individual shall be held liable for assets that were previously acquired. It should also be noted that the principles enshrined in Article 58 of the Constitution of Ukraine and Articles 4, 5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which apply to other articles of the Criminal Code, apply to this article as well. For convenience, please see the infographic:

Thus, the reasoning of the petition authors that Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine presumably applies to assets acquired before the entry into force of the law is unfounded. They are based on an arbitrary understanding and interpretation of Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, which is contradictory to both the Constitution of Ukraine and the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

CONCLUSION:

1. Article 58 of the Constitution of Ukraine stipulates that laws and other regulatory acts do not have retroactive effect, except in cases when they mitigate or cancel a person’s liability. Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine is no exception to this rule. The disposition of this article does not in any way indicate any retroactive effect of this provision. Liability for committing a crime stipulated by Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine occurs after a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government has acquired assets that exceed their legal income. This means that assets acquired by the person before the provision has come into effect are not taken into consideration when the issue of liability arises.

CIVIL FORFEITURE

A. LEGAL NATURE OF CIVIL FORFEITURE

- Civil forfeiture is not a form of punishment.

- The institution of civil forfeiture operates outside the scope of criminal law.

- The option to file a lawsuit to third parties is consistent with the best international practices, protects property rights, and ensures procedural guarantees.

- Civil forfeiture is established by law and can only be administered by court decision, which is fully consistent with the Constitution of Ukraine.

The authors of the constitutional petition claim that:

“in its legal nature, the institution of recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue, while connected with a lawsuit within civil proceedings, effectively constitutes another type of punishment alongside confiscation and special confiscation.”

As key arguments supporting the claim, the authors indicate the following:

1. Recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue completely duplicates confiscation and special confiscation as measures of punishment and liability for illegal acts. Duplication of punishment and administration of confiscation, special confiscation, and civil forfeiture to an individual violates the principle of proportionality which requires proportionate restriction of rights and freedoms of an individual to achieve public goals.

2. This, in turn, contradicts the principle of the rule of law and does not take into account the legal positions of the CCU, whose decisions have repeatedly emphasized the fairness of punishment, its relevance and the proportionality to the crime.

3. Civil forfeiture violates the principle of proportionality of punishment.

Confiscation and forfeiture are not a form of punishment. They cannot violate the principle of proportionality of punishment.

The authors of the constitutional petition have an erroneous idea about the institution of civil forfeiture. They consider it another type of punishment alongside confiscation and special confiscation. However, the authors do not take into account a number of important differences between them.

Article 62, part 1 of the Constitution of Ukraine stipulates that an individual is considered innocent of the commission of a crime and may not be subjected to criminal punishment until their guilt is proved in a lawful manner and established by a court conviction. Under Article 50, part 1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, punishment is a measure of coercion administered on behalf of the state based on a court verdict to an individual found guilty of a criminal offense and consists in restriction of the convict’s rights and freedoms as provided by law.

One important fact follows from these provisions: punishment is applied to a person found guilty of a criminal offense. That is why the concept and purpose of punishment, its types are enshrined in the Criminal Code of Ukraine. It is important that punishment is administered only after the guilt of the person is established by a court conviction.

At the same time, the institution of civil forfeiture operates outside the scope of criminal law. This follows directly from the Code of Civil Procedure, Article 290, parts 2 and 6. This provision establishes that:

“a lawsuit is filed in relation to assets... if the difference between their value and the legal income of the person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government exceeds the subsistence minimum for able-bodied persons established by the law as of the day of the Law coming into effect by a multiple of five hundred and more, yet does not exceed the limit established by Article 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine.”

The Ukrainian model of civil forfeiture is closely linked to the institution of illicit enrichment and is in fact its «procedurally facilitated» version. As the Colombian Constitutional Court has aptly pointed out, the concept of illicit enrichment is much broader than the concept of criminal offense. It does not fit within the framework of criminal law and also falls within the scope of property law. It covers the outcomes of illegal activity and failure of the perpetrator to comply with the social order in the sphere of property relations in criminal offenses. So the purpose is not only to punish the offender, but also to deprive the offender of ownership of assets obtained as a result of criminal or illegal acts, misuse of public funds. Considering these differences and purposes, civil forfeiture of property is separated from criminal proceedings.

CONCLUSION:

1. Civil forfeiture is not a criminal institution. It does not constitute punishment as understood by the Criminal Code. Civil forfeiture is aimed at the return of the state’s assets in a lawsuit under the rules of civil procedure.

B. THIRD PARTY RIGHTS AND THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE

The authors of the petition believe that the institution of recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue allows to apply negative consequences which constitute part of criminal liability and constitute punishment by tneir legal nature to innocent third parties.”

The authors of the constitutional petition insist that:

“the statutory concept of recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue applies to cases of acquisition of assets by another natural or legal person if it has been proven that such acquisition has taken place on behalf of a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government or that a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government can perform actions directly or indirectly in connection with such assets which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets.”

The authors of the petition also note that the institution of civil forfeiture provides for

“the possibility to file a lawsuit on recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue to another natural or legal person, who has acquired such assets into property on behalf of a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government or if a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government can perform actions directly or indirectly in connection with such assets which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets.”

The authors of the petition believe that such a legislative approach contradicts the constitutional principles of bringing a person to liability, the principle of the rule of law, and the principle of individual nature of legal liability, enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine, Article 61, part 2.

The liability established for the acquisition of unjustified assets is individual. The possibility to file a lawsuit on recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue to a third-party natural or legal person is consistent with the best global practices and protects the rights of such persons.

The law obliges law enforcement to provide factual data on (Code of Civil Procedure, Article 81):

1. the relationship between the assets and the authorized person: both direct (the authorized person has acquired property de jure) and indirect (the authorized person has acquired property de facto, but de jure ownership belongs to third parties);

2. the fact that such assets are unexplained.

It follows from the Code of Civil Procedure, Article 290, part 8, clause 2 that law enforcement authorities must prove the fact of direct or indirect ownership of property. This obligation follows from the very idea of “acquisition of assets,” which is used for the purposes of the Code of Civil Procedure, chapter III, section 12, and is enshrined in Article 290 of the Code of Civil Procedure, part 8, clause 2.

According to this provision, a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government acquires certain assets in three cases:

- Acquisition of assets into property;

- Acquisition of certain assets by other persons, if it has been proven that such acquisition was carried out on behalf of the public official;

- Acquisition of certain assets by other persons, if it has been proven that a public official can perform actions directly or indirectly in connection with such assets which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets.

Therefore, the rights of third parties are not violated in any way. To file a lawsuit on recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue to a third-party natural or legal person, law enforcement officers must prove the connection between the third-party property and the public official. Simply put, it is necessary to prove the “de facto” property right of the public official for such assets.

What is more, the option to file a lawsuit to the legal owner of the property is the right approach considering civil law. This approach is considered justified, because civil forfeiture in personam (against a person) is especially useful for the return of assets derived from corruption and embezzlement of state assets, because it begins with the inspection of a particular subject. In addition, it helps to avoid the risk of violating the procedural rights of owners, because non-notification on the start of the respective proceedings is inadmissible. The lawsuit is filed against the legal owner of the property, all interested parties must be notified, and the confirmation of this must be presented to the court together with the lawsuit. From the moment of filing a lawsuit to declare the assets unfounded, all persons whose rights may be violated must be involved as third parties who do not make independent claims. According to the Code of Civil Procedure, Article 43, such third parties are considered participants of the case and have all the relevant rights (from providing evidence to appealing the decision). This is a critical provision, as it is the «procedural» side of the defense that is essential for recognizing confiscation and forfeiture as proportionate in the case law of the ECtHR.

The law also provides for an opportunity to file a lawsuit against the legal owner of property considering the practice that Ukraine sees a common practice of “assigning” property to third parties, while the public official is the one who effectively owns the property. The law had to take this into consideration to ensure effective work of the institution of recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue. What is more, this approach is consistent with the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention” and the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

The authors of the petition claim that civil forfeiture “shifts the burden to prove their innocence and provide the respective evidence to the person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government.”

The main argument of the authors of the submission to support this position is as follows:

“In accordance with the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” Article 50, part 3, if the National Agency identifies signs of unexplained assets following a full verification of the declaration, it provides the person subject to declaration to provide a written explanation of that fact with the respective evidence. In case the subject fails to provide a written explanation and evidence, or does not provide them completely, the National Agency notifies the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office of this.”

“Thus, if a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government does not provide proof that assets or funds required for the purchase of assets were acquired through legal means, such an individual immediately becomes a perpetrator with negative legal consequences stipulated by section 12 of chapter III of the Code of Civil Procedure of Ukraine, or, if criminal offense is identified, such a person is brought to criminal liability.”

A person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government is not automatically brought to liability for failure to provide a written explanation. Such a person is not obliged to prove their innocence. Civil forfeiture is carried out within civil procedure, where the standard of proof is lower than in criminal proceedings.

It is worth noting that the authors of the constitutional petition again deliberately distort the content of the law. They manipulate legislation, interpreting it contrary to logic and common sense.

For example, the provision of Article 50 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” which they believe to oblige a person to provide evidence of their innocence, is actually aimed at the exact opposite. The main purpose of this rule is to avoid unfounded appeals to law enforcement agencies with a claim about the possible commission of an offense. The law actually provides the person with an opportunity to explain their vision of the situation if violations are identified. It is also important to highlight that this provision does not in any way oblige the public official to prove their innocence.

Moreover, there is nothing in the provision about any automatic violation of the law and especially about any negative legal consequences in case of failure to submit an explanation.

First, it follows from the very Article 50 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention,” which clearly states that if a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government fails to submit an explanation, the NACP is first of all supposed to inform the NABU and the SAPO. This only means that the NABU will start to conduct an investigation and collect evidence of the person’s guilt, and only after that can the other agency, the SAPO, go to court.

Secondly, the negative consequences provided by Chapter III, section 12 of the Code of Civil Procedure of Ukraine, cited by the authors of the petition, occur only following the court decision.

Therefore, the arguments in the petition are not true to fact.

It should be emphasized that, in providing the reasoning for their position, the authors of the constitutional petition frequently equate civil proceedings with criminal proceedings. What is important in this context is that the standard of proof in these types of proceedings is different.

In this context, we can look at the standard of proof in proceedings connected with the institution of recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue. To accomplish this, we invite you to consider the following excerpt from the aforementioned study, since it clearly explains the standard of proof applied in civil forfeiture:

“The law has defined the standard of proof as preponderance of evidence, i.e. the standard of proof has been maintained if it has been proven that the subjective probability of the contested fact having happened exceeds the probability of the opposite. The law does not explicitly state this, but the “preponderance of evidence» usually means that the assumption is true rather than false, i.e. the probability of its truth is more than 50%. The use of this standard of proof instead of the standard “beyond a reasonable doubt,” which is applied in criminal proceedings, is often criticized by individuals whose property is subject to forfeiture. At the same time, both national courts and the ECtHR state that the application of this standard is justified in cases when the forfeiture / confiscation process occurs within civil proceedings.

For example, in the case Walsh v. Director of the Assets Recovery Agency, the litigant insisted that a stricter standard of proof had to be applied due to the fact that the case was first considered within criminal proceedings and only afterwards transitioned into civil proceedings. Such a situation is also stipulated by the Ukrainian legislation, which is why we believe it is likely to frequently occur in the process of recognizing assets as unexplained.

Applying the three Engel criteria: 1) classification in domestic law; 2) nature of the offense; and 3) severity of the penalty that the person concerned risks incurring, the Court of Northern Ireland concluded that “the essence of article 6 [of the ECHR] in the criminal dimension is the charging of a person with a criminal offence for the purpose of securing a conviction with a view to exposing that person to criminal sanction. These proceedings are obviously and significantly different from that type of application. They are not directed towards him in the sense that they seek to inflict punishment beyond the recovery of assets that do not lawfully belong to him. As such, while they will obviously have an impact on the appellant, these are predominantly proceedings in rem. They are designed to recover the proceeds of crime, rather than to establish, in the context of criminal proceedings, guilt of specific offences.” Thus, the court concluded that such cases are civil in nature. Therefore, the application of a stricter standard of proof, which is used in criminal proceedings, is not mandatory.

What is more, the ECtHR itself is guided by higher standards of proof in its proceedings, but the Court has found it necessary to depart from the standard “beyond a reasonable doubt” in proving certain circumstances. As a result of the Government’s failure to provide significant evidence or significant explanations concerning certain circumstances to be proven by the other party, the Court indicated the possibility of drawing adverse inferences and making the decision on such circumstances with the application of a much lower standard of proof, i.e. preponderance of evidence (Judgment in the case Trepashkin v. Russia (No. 2) of 10.12.2010, § 107). Please note that the Court has chosen to use a simpler standard of proof for reasons that are extremely likely to arise in cases concerning unexplained assets -- unwillingness of one of the parties to provide evidence that is relevant to the decision.

The Code of Civil Procedure does not contain special requirements for evidence to be provided by both parties. Evidence which, under the general rule (section 5 of the Code of Civil Procedure), is used in civil proceedings, must also be used in cases on recognition of assets as unexplained. During the recent legal reform, the institution of proof in civil proceedings underwent significant change, which directly impacts the quality of proof in cases on recognizing assets as unexplained.

The duties of the parties include, inter alia, submission of all available evidence pursuant to the procedure and time frame established by the law or by court and non-concealment of evidence (Code of Civil Procedure, Article 43, part 2). This principle is critical in the context of concealment of evidence, as both law enforcement agencies and the defendant will try to cover only the facts which, respectively, support or refute the claims. Such balance should be preserved:

A) first, by expanding the discretion of the court in the field of proof, in particular by giving it the opportunity to collect evidence on its own initiative in exceptional cases — when it has doubts about the conscientious exercise of the parties’ procedural rights or obligations as to evidence, and as well as other cases provided by the Code (Code of Civil Procedure, Art. 13, part 2; Art. 82, part 7);

B) secondly, due to the fact that the court is authorized to apply measures of procedural coercion in cases of abuse of procedural rights and failure to comply with the obligations of evidence (Code of Civil Procedure, Article 84, part 8, Article 143, part 1, Article 146; Article 148, part 1, clauses 1, 2).

Despite criticism of the possible violation of the adversarial parties principle, these provisions of the procedural legislation on the option to require evidence on the initiative of the court in case of dishonest conduct of the parties concerning evidence, are designed to maintain the balance between the adversarial principle, which ensures the exercise of private legal interest in civil proceedings, and the court activity in the context of judicial management of the proceedings, which reflects the public legal interest in the effectiveness of civil proceedings. The need to maintain this balance follows directly from the objective of civil proceedings — fair, impartial and timely trial and resolution of civil cases for the purpose of effective protection of violated, unrecognized or disputed rights, freedoms, or interests of natural persons, the rights and interests of legal entities and state interests (Code of Civil Procedure, Art. 2, part 1).

The right of interested parties to provide evidence merits special attention. Interested parties are notified of the lawsuit and are engaged as third parties who do not make independent claims. At the same time, such persons are participants of the case (Code of Civil Procedure, Art. 42, part 1) and, on par with the claimant and the defendant, have the right to submit and examine evidence, participate in court hearings, file motions, petitions and objections, and appeal against court decisions (Code of Civil Procedure, Art. 53, part 6; Art. 43, part 1).”

CONCLUSIONS:

1. The statutory concept of recognition of assets as unexplained and their collection to the state revenue is clear and understandable. It applies only to cases of acquisition of assets by a person authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government or cases of de facto disposal of assets by such a person. The possibility to file a lawsuit against the “legal” owner of the property serves to ensure their procedural rights, which is consistent with the ECtHR practice.

2. The law does not provide for automatic administration of punishment to a person in case of non-submission of written explanations as per Article 50 of the Law of Ukraine “On Corruption Prevention.” Civil forfeiture is administered only at the court decision and following proof by law enforcement agencies in court of the fact that the public official’s assets are unexplained, as well as of his/her connection with said assets.

3. The standard of proof in civil proceedings is lower than in criminal proceedings. In this category of cases, it is justified and fully complies with ECtHR standards.

C. LEGAL CERTAINTY

The authors of the petition claim that the provisions regulating civil forfeiture are not consistent with the principle of legal certainty due to the fact that the law is not foreseeable and not clear. They say:

“Namely, the contested provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure of Ukraine and the Laws of Ukraine ‘On Corruption Prevention,’ ‘On Prosecution,’ ‘On the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine,” “On the State Investigation Bureau,’ ‘On the National Agency of Ukraine for finding, tracing and management of assets derived from corruption and other crimes,’ contain the following concept in the context of actions with assets: ‘identical in their content to the right to dispose of assets.’ In this regard, the question arises how to define the concept of something being ‘identical in their content to the right to dispose of assets.’ What does ‘identical’ mean?”

The provisions of the Law are clear and understandable. They comply with the principle of legal certainty. The provisions of the law make the concept “identical in their content to the right to dispose of assets” clear.

We dwelled on the fundamental nature of the principle of legal certainty in greater detail of section 2, item A of this brief. Here, we provide reasoning connected with the contested provision.

Below is an excerpt from the caveats mentioned in this section of the study:

“Ukrainian law stipulates that civil forfeiture is applied only to unexplained assets which directly or indirectly belong to persons authorized to perform the functions of state or local self-government (hereinafter — public official).

Direct ownership means assets which officially belong to the public official.

Indirect ownership means that officially, the assets belong to third parties, but such third parties have acquired them on behalf of the public official, or the public official can perform actions directly or indirectly in connection with such assets which are in their content identical to the right to dispose of assets.

What “on behalf of” means

In the first case, there is indeed a risk of too narrow an interpretation of the idea of performing actions “on behalf of” a public official, which can also shift into the realm of “power of attorney” in the Ukrainian language. Civil law (Section 68 of the Civil Code of Ukraine) considers “power of attorney” as a contract under which one party (attorney) undertakes to perform certain legal actions on behalf and at the expense of the other party (principal). The code does not contain a mandatory requirement for the form of the contract. Therefore, this agreement can be concluded both orally and in writing. At the same time, the Civil Code of Ukraine, Article 1007 obliges the principal to issue a power of attorney to the attorney to perform legal actions under the agreement, regardless of the form of the agreement.

It clearly follows from the Civil Code, Article 244, part 3 that power of attorney is always done in writing. In turn, the Civil Code of Ukraine, Article 245, part 1 establishes that the power of attorney must correspond to the form of the transaction in question that the principal authorizes the attorney to perform. That is, in case of transactions on acquisition of assets, most of which require an agreement not just in writing, but also notarized (the right to dispose of real estate, management and disposal of corporate rights, use and disposal of vehicles), the power of attorney must also be in writing and notarized.

We hope that the judges will not interpret “behalf” as “power of attorney” as described above. If a person intends to conceal illegally acquired income, they are unlikely to use written agreements to acquire such assets through a third-party formal owner. The existence of a spoken agreement is almost impossible to prove when both parties deny the fact of its conclusion. The analysis of a number of court decisions has shown that the phrase “on behalf of” is used as synonymous to the phrase “as instructed by.” Apart from formal instructions (written instructions, payment orders, etc.), all other instructions concerning actions performed on behalf of public officials were received in a spoken form. And the only way to see if such instructions have been given was to take the word of persons who received such instructions.