>

Analysts>

Evidentiary standards in the practice of the UN Compensation Commission: Lessons for UkraineEvidentiary standards in the practice of the UN Compensation Commission: Lessons for Ukraine

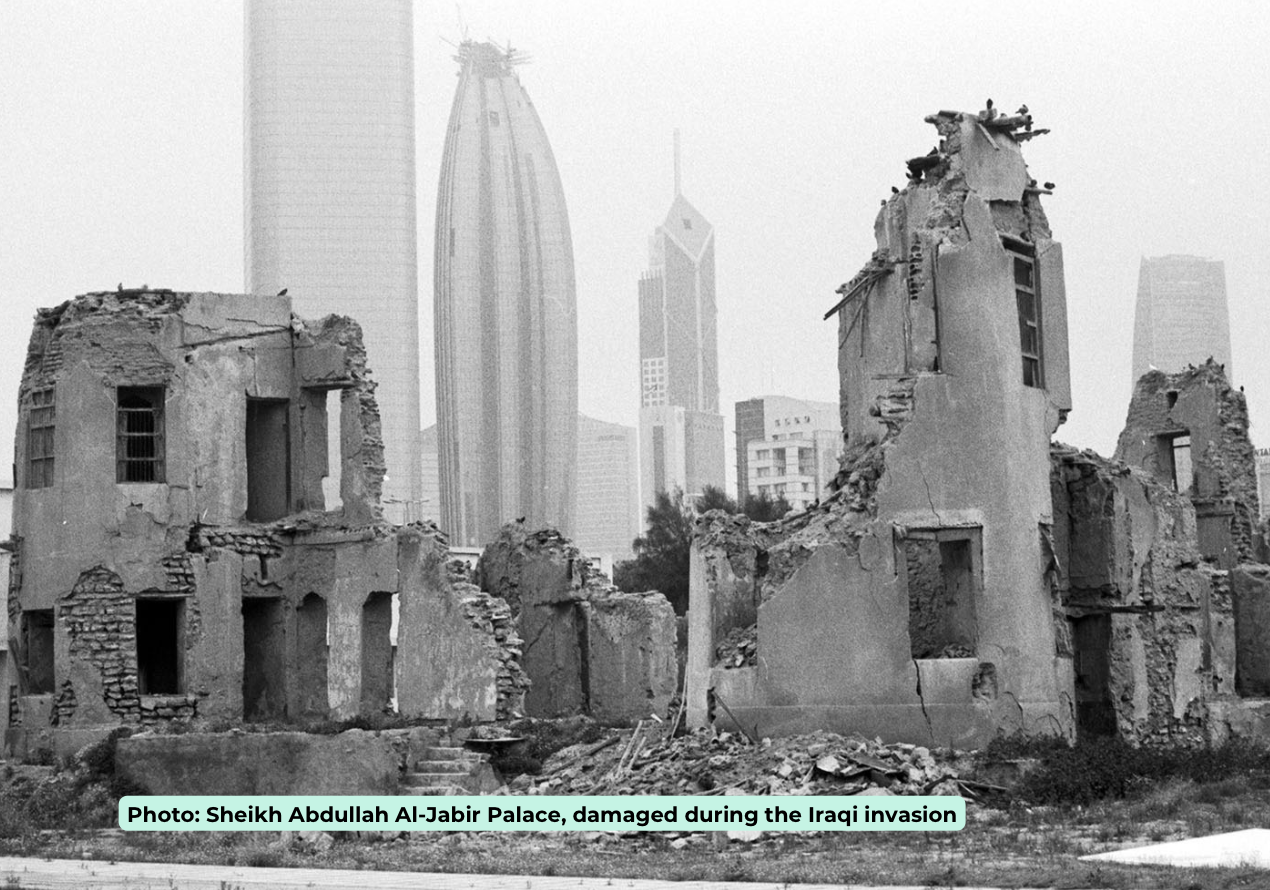

This document contains our analysis of the practice of the UN Compensation Commission, which was established in 1991. by the UN Security Council to consider claims and pay compensation for damage and losses caused by Iraq's illegal invasion of Kuwait and subsequent occupation of Kuwait in 1990-1991.

This is a successful case of implementing a compensation mechanism, the experience of which should be taken into account when implementing the Global Compensation Mechanism for Ukraine after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation in February 2022.

Publisher: think tank “Institute of Legislative Ideas”. All rights reserved.

Authors: Tetiana Khutor, Bohdan Karnaukh, Andrii Klymosyuk

Photo sources: AFP, Rare historical photos. Cover photo - For the first time in Kuwait's history, the country's main towers were illuminated with the flag of another state on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the restoration of independence, 2021

Introduction

Summary

The aggressive war waged by the Russian Federation against Ukraine causes tremendous devastation. According to the World Bank the estimated cost of reconstruction amounts to USD 486 billion (as of December 2023). According to other estimates, the total amount of damage may be close to USD 1 trillion.

These figures do not take into account the heaviest of all losses - human casualties. According to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, as of the February of 2024, civilian casualties alone amounted to 30,755 people, including 10,675 killed and 20,080 injured. And these figures are always presented with the caveat that the real losses may be much higher, as statistics reflect only confirmed cases, while in wartime it is often impossible to obtain verification.

A huge number of Ukrainians had to leave their homes: according to the Ministry of Social Policy, the number of officially registered internally displaced persons in the country currently reaches 4.9 million (Internally Displaced Persons, n.d.). About 6 million Ukrainians were forced to flee the country. All of it is a consequence of the aggressive war waged by the Russian Federation against Ukraine.

According to international law, a state responsible for internationally wrongful acts is obliged to compensate in full for the damage caused by such acts (Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, Article 31).

Thus, all damage caused by the Russian aggression must be compensated by the aggressor state. To this end, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe adopted a Resolution (Resolution CM/Res(2023)3), which introduced the first of three elements of the international compensation mechanism for Ukraine, namely the International Register of Damages Caused by the Aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine.

Section I

About the Commission in general

The United Nations Compensation Commission (hereinafter referred to as the Commission) was established in 1991 pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 692 to consider claims and pay compensation for damage and losses caused by Iraq's illegal invasion of Kuwait and subsequent occupation of Kuwait in 1990-1991.

The legal basis of the compensation mechanism was the provision of paragraph 16 of UN Security Council Resolution 687, according to which:

“Iraq… is liable under international law for any direct loss, damage - including environmental damage and the depletion of natural resources - or injury to foreign Governments, nationals and corporations as a result of its unlawful invasion and occupation of Kuwait”.

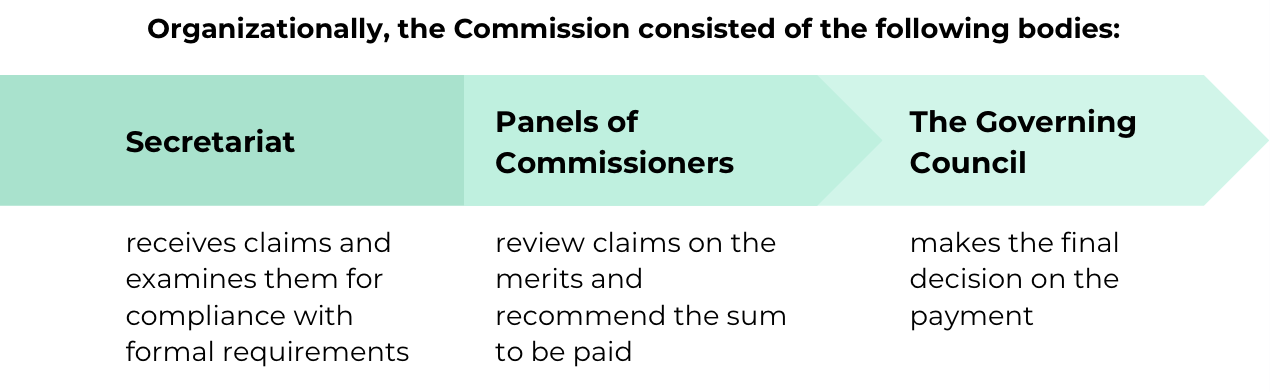

The Commission was not a court or tribunal, as there was no need to establish Iraq's responsibility - the internationally wrongful character of the invasion was established by the UN Security Council and openly acknowledged by the Iraqi government. The Commission's rules do not provide for detailed adversarial procedures. Therefore, the Commission's operations were more of an administrative rather than a judicial nature. Its task was mainly to establish the facts and determine the amount of compensation(1).

Injured individuals and legal entities did not submit claims to the Commission directly, but through their governments, which collected these claims in the field and submitted them to the Commission in consolidated packages.

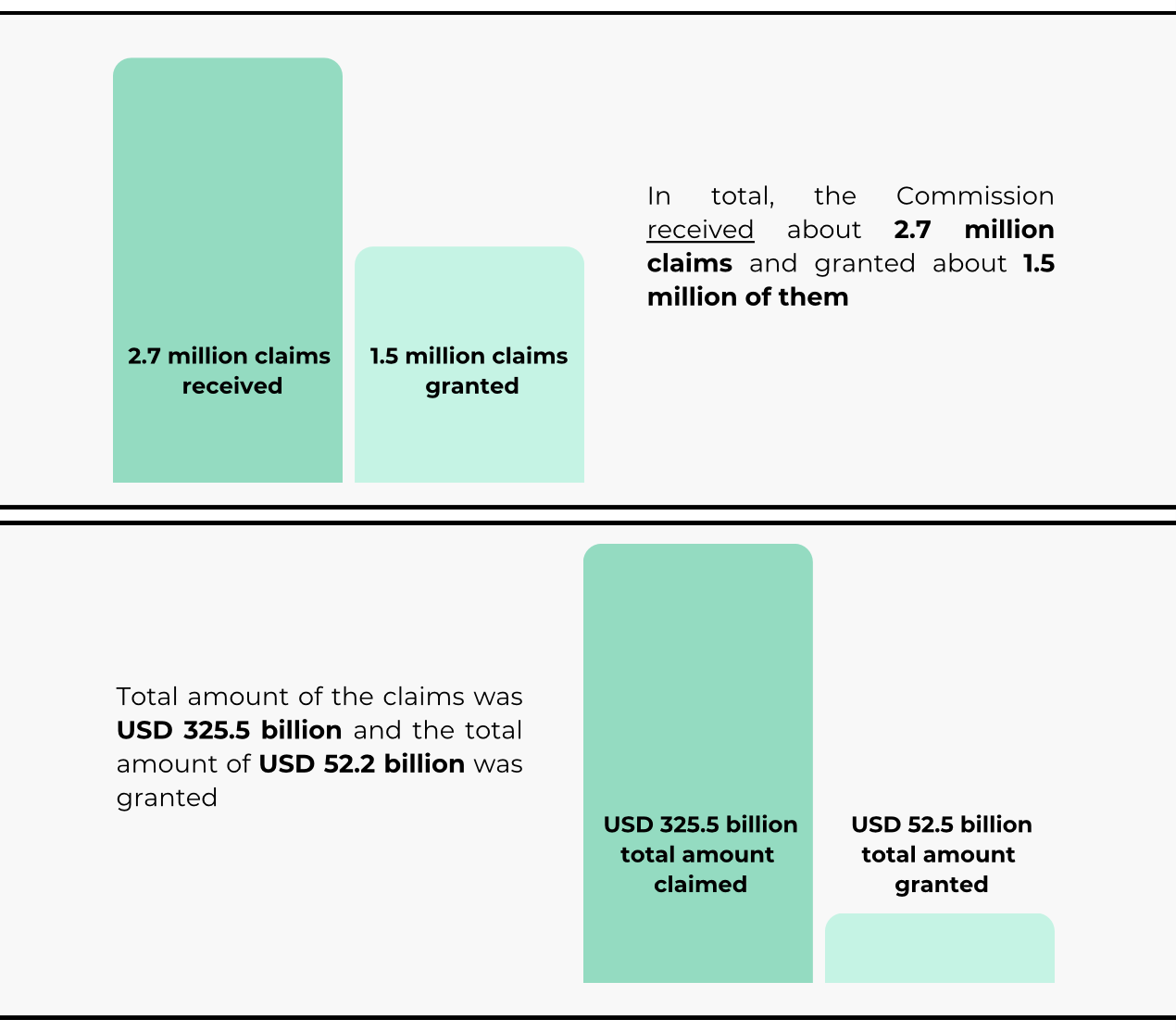

Commission worked for 31 years and completed its work, having made payments in full, at the end of 2022.

The President of the Commission's Governing Council presented the Final Report to the UN Security Council two days before the Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, on February 22, 2022.

Section II

Categories of claims

The Governing Council has defined six categories of claims:

These claims were filed by people who were forced to leave Kuwait or Iraq between August 2, 1990 (the day of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait) and March 2, 1991 (the day of the ceasefire).

The amount of compensation for this category was fixed at USD 2,500 per person and USD 5,000 per family. However, if the applicant did not claim compensation under any other category, the amount was USD 4,000 and USD 8,000, respectively.

"Serious personal injury" has been defined in Decision 3 to mean:

a) Dismemberment;

b) Permanent or temporary significant disfigurement, such as a substantial change to one’s outward appearance;

c) Permanent or temporary significant loss of use or limitation of use of a body organ, member, function or system;

d) Any injury which, if left untreated, is unlikely to result in the full recovery of the injured body area, or is likely to prolong such full recovery(2).

The amount of compensation for such claims was USD 2,500 per person and USD 10,000 per family. However, if a person believed that this amount was not sufficient to remedy the damage, he or she could also file a category C claim.

Claims in this category included twenty-one types of damages, including: damage related to leaving Kuwait or Iraq, serious personal injury, mental pain and anguish, loss of property, loss of bank accounts, shares and other securities, loss of income, loss of real estate, and individual business losses.

This category included eight subcategories:

C1: Damages arising from departure from Iraq or Kuwait, inability to leave Iraq or Kuwait, a decision not to return to Iraq or Kuwait, hostage taking or other illegal detention;

C2: Damages arising from personal injury;

C3: Damages arising from death of [the claimant's] spouse, child or parent;

C4: Personal property losses;

C5: Loss of bank accounts, stocks and other securities;

C6: Loss of income, unpaid salaries or support;

C7: Real property losses;

C8: Individual business losses.

In addition, for the sub-categories C1, C2, C3 and C6, applicants could also claim compensation for mental pain and anguish (MPA) in accordance with the standards and limits set out in Decisions 3 and 8 of the Governing Council(3).

The types of damage were the same as in category "C".

Such claims related to losses under construction or other contracts, losses from non-payment for goods or services, losses related to the destruction or seizure of business assets, lost profits, losses in the oil sector, etc.

Such claims covered the costs incurred by states in evacuating their citizens, providing them with aid, damages in connection with the destruction of diplomatic buildings, loss or damage to other state property, as well as environmental damage and depletion of natural resources in the Gulf region, including as a result of oil well fires and oil dumps into the sea.

2) See: Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Individual Claims For Serious Personal Injury or Death (Category “B” Claims), 26 May 1994, p. 20.

3) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages Up To Us$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 7.

Section III

Prioritization and expedited procedure

An important innovation of the Commission was granting priority to individual claims of affected natural persons over claims of governments and corporations, as it was the case before. This humanistic and victim-centered approach was a significant step in the evolution of international compensation mechanisms.

The Governing Council decided(4) to consider under the expedited procedure and treat as urgent individual claims of victims in categories "A" (forced abandonment of Kuwait or Iraq), "B" (serious personal injury and/or death of a family member) and "C" (various types of damage up to $100,000).

Specific features of the expedited procedure are provided for in Article 37 of the Provisional Rules For Claims Procedure. These, in particular, include the use of special methods of analyzing claims, including computerized comparison of claim details with verification data, sampling, statistical modeling, absence of oral hearings, etc.

Pursuant to Article 37(d) of the Provisional Rules, each panel of commissioners had to complete its review of the claims submitted to it and publish a report as soon as possible, but no later than 120 days from the date of submission of the claims to the panel.

In decision S/AC.26/1991/1, the Governing Council stated:

“For a great many persons these procedures would provide prompt compensation in full; for others they will provide substantial interim relief while their larger or more complex claims are being processed, including those suffering business losses” (para 1).

Thus, a person who suffered significant economic losses of more than USD 100,000 could file a category C claim and receive at least partial compensation through the expedited procedure, and at the same time, based on the same facts, file a category D claim (claims over USD 100,000) under the regular procedure, prove that his or her losses were actually greater and eventually receive full compensation.

The expedited processing of the three categories of claims was also made possible due to the lowered standards of proof established for these categories by the decision of the Governing Council S/AC.26/1991/1 (discussed further).

Section IV

Burden of proof

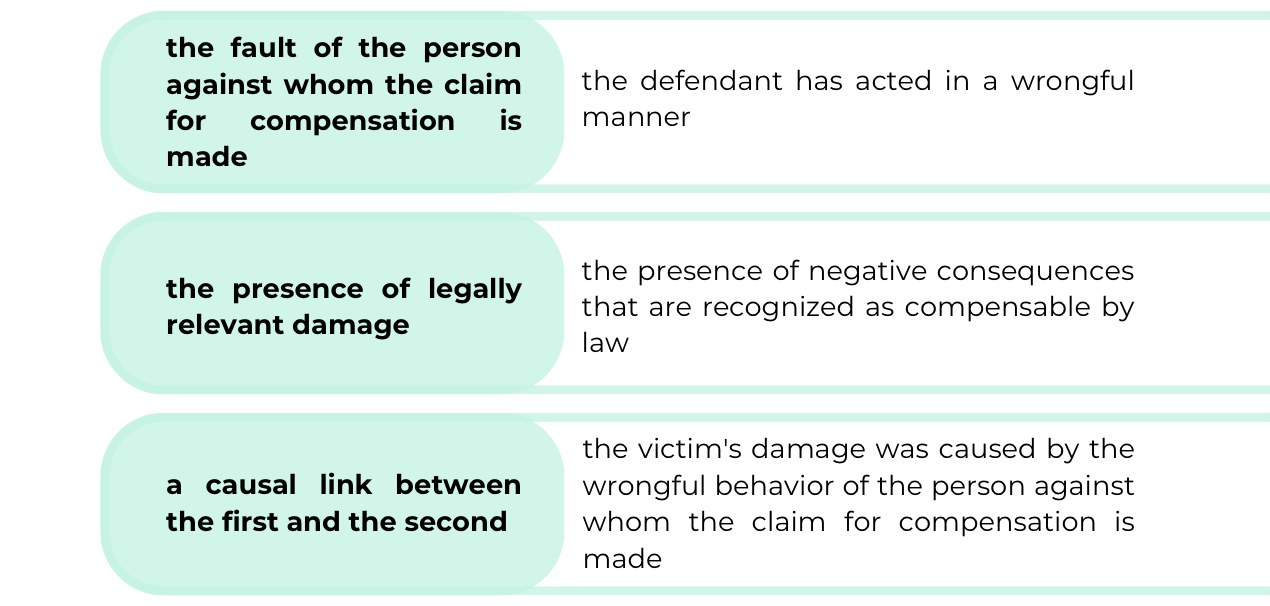

According to the general principles of tort law, the injured person has to prove:

However, as has been noted above, there was no need for the Commission to establish Iraq's fault - the fault had already been established by the UN Security Council and acknowledged by the Iraqi government itself.

Thus, the Commission's task was to verify:

To this should also be added the task of determining the amount of compensation, which, from a theoretical point of view, can either be considered part of the first question (presence of damage) or can be separated into a distinct inquiry.

Section V

Evidentiary standards

As a general rule, the burden of proof of a certain fact rests with the person who relies on that fact to support his or her legal standing (claim, action, complaint or objection). According to this rule, a claimant applying to the Commission has to prove with relevant evidence that he or she has suffered legally cognizable damage, justify its amount, and demonstrate that it was the result of Iraq's internationally wrongful acts.

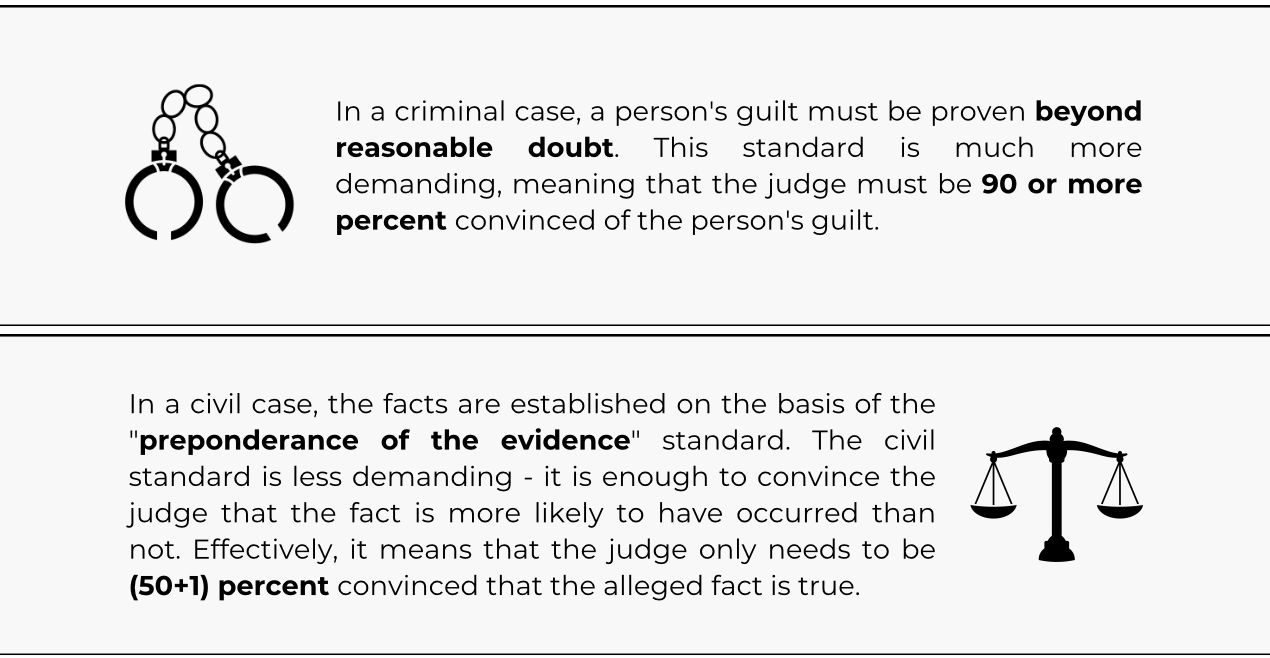

Standards of proof are of key importance in the context of probative activities. The standard of proof indicates the level of exaction with respect to the evidence submitted to prove a particular fact.

It is a sort of "bar" that the party has to meet in order for its legal stance to be recognized as well-founded. Depending on the procedural rules, this bar may be higher or lower, and, accordingly, the exaction will be greater or lesser.

For example, the standards of proof for criminal and civil cases are different.(5)

However, the consideration of claims by the Commission and similar institutions in the past has a number of distinct features that require a specially tailored, flexible and diversified approach to setting the "evidentiary bar" that claimants have to overcome. In particular, the claimants' ability to collect evidence was affected by the exceptional circumstances of the harm: in times of military aggression and occupation, collecting evidence is far from being a top priority for individuals. People are forced to flee the war in a hurry, leaving their belongings behind, and in this mess, needed documents could be lost, stolen or ruined. The operation of various government agencies and institutions is disrupted by the war, making it difficult to keep track of various civil status acts and other events that normally would have been officially documented.

In recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1, the Commission stated:

“The scarcity of evidentiary support characterizing many claims may be attributable mainly to the circumstances prevailing in Kuwait and Iraq during the invasion and occupation period. Under the general emergency conditions prevailing in the two countries, thousands of individuals were forced to flee or hide, or were held captive, without retaining documents that later could be used to substantiate their losses. In addition, many claimants chose not to or could not return to Iraq or Kuwait, and therefore had difficulty producing primary evidence of their losses,damages or injuries.”

These circumstances, coupled with the large number of claims that the Commission had to process, made it inefficient and infeasible to apply the regular standards of proof used in civil or criminal proceedings. Therefore, it was a natural step to establish special, lowered requirements for evidence to prove the damage caused.

In doing so, the Commission noted that this practice is common for similar international compensation mechanisms:

“The scarcity of evidentiary support where massive numbers of claims are involved is not a phenomenon without precedent in international claims programs, in particular if the events generating responsibility have taken place in abnormal circumstances such as those prevailing in Kuwait and Iraq during the conflict. An analysis of the practice of international tribunals regarding issues of evidence shows that tribunals often had to decide claims on the basis of meagre or incomplete evidence. It has been observed that the lowering of the levels of the evidence required occurs especially "in the case of claims commissions, which have to deal with complex questions of fact relating to the claims of hundreds or even thousands of individuals".(6)

Secondly, in addition to the context of the armed conflict, the Commission also took into account the realities of national practice in the respective country of the victims' origin when determining the level of exactingness in respect of evidence. For example, the Commission took into account the fact that Kuwait's economy is mainly cash-based, which has an impact on the specifics of proving the transactions and settlements made under them.(7)

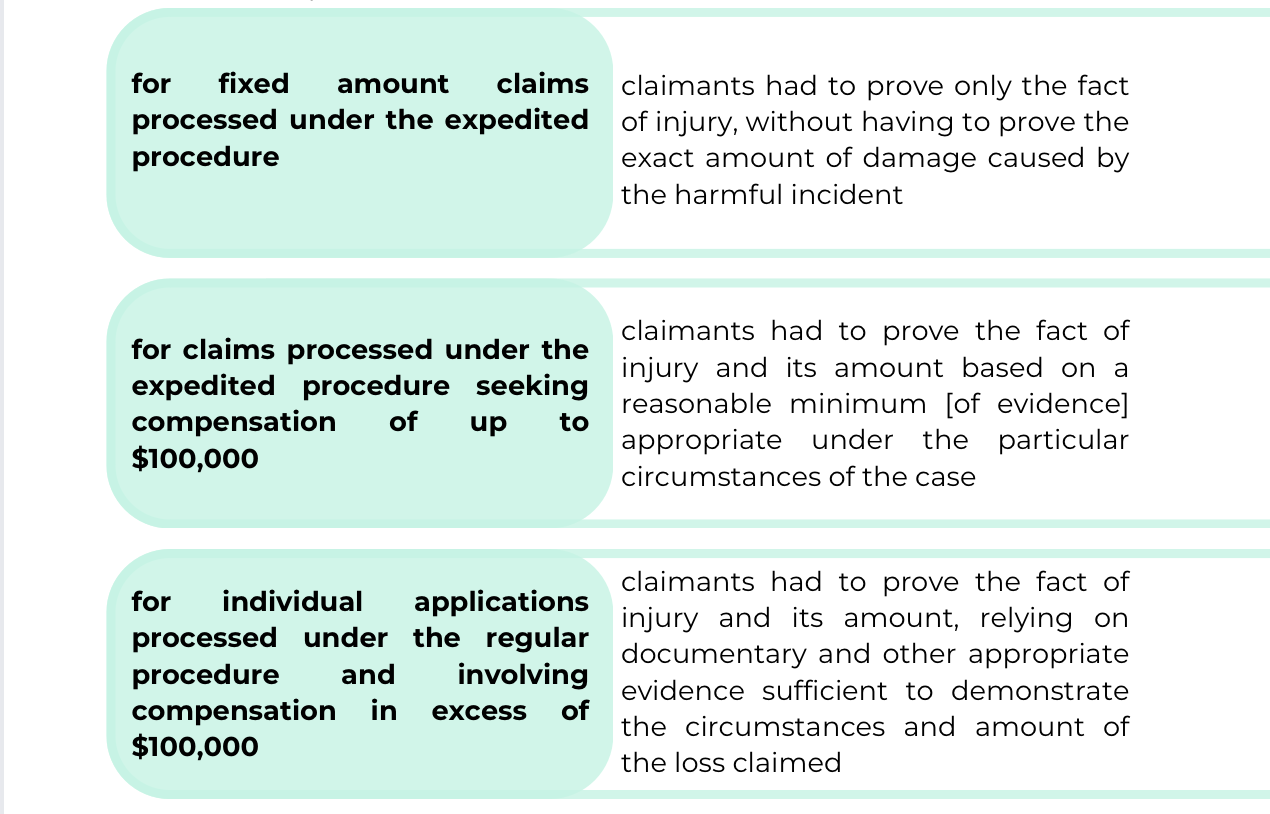

Thirdly, the Commission applied a diversified approach - different standards of proof were applied to different categories of claims. The exactingness depended directly on the amount of compensation claimed by the applicant: the lower the amount, the lower the requirements for proving damage, and vice versa. Moreover, in some cases (when the amount of compensation was fixed), even the burden of proof changed.

Thus, in category A (forced displacement) claims, for example, there was no need to prove the amount of damage at all: the applicant had only to demonstrate that he or she had left the country during a specified period of time (from the date of the invasion until the date of the ceasefire). The claimant did not have to provide any explanation or evidence regarding the costs or damages that such forced displacement entailed.”

In accordance with paragraph 11 of Governing Council decision S/AC.26/1991/1 of August 2, 1991:

“11. In the case of departures, $2,500 will be provided where there is simple documentation of the fact and date of departure from Iraq or Kuwait. Documentation of the actual amount of loss will not be required.”

The same applied to claims for serious personal injuries and death of family members, where applicants claimed a fixed amount:

“in the case of serious personal injury not resulting in death, $2,500 will be provided where there is simple documentation of the fact and date of the injury; and in the case of death, $2,500 will be provided where there is simple documentation of the death and family relationship. Documentation of the actual amount of loss resulting from the death or injury will not be required. If the actual loss in question was greater than $2,500, these payments will be treated as interim relief, and claims for additional amounts may also be submitted under paragraph`14 and in other appropriate categories.”(8)

The last, third category of claims reviewed under the expedited procedure did require the proof of the amount of damages suffered. For this category, the Governing Council established a special evidentiary standard of "a reasonable minimum [of evidence] appropriate under the circumstances." At the same time, it is stipulated that claims for smaller amounts (up to $20,000) require less documentary evidence.

In accordance with paragraph 15(a) of decision S/AC.26/1991/1

“Such claims must be documented by appropriate evidence of the circumstances and the amount of the claimed loss. The evidence required will be the reasonable minimum that is appropriate under the circumstances involved, and a lesser degree of documentary evidence would ordinarily be required for smaller claims, such as those below $20,000.”

Finally, the most demanding standard applied by the Commission was set for "D", "E" and "F" categories of claims. Such claims had to be supported by "documentary and other appropriate evidence sufficient to demonstrate the circumstances and amount of the claimed loss" (Article 35(3) of the Provisional Rules for Claims Procedure). However, the Commission in its Report S/AC.26/1998/1 emphasized that even this, most demanding standard, is not commensurate with the high criminal law standard "beyond a reasonable doubt" - instead, it is rather closer to the civil law standard of "preponderance of the evidence", with the caveat that it should also be adjusted for the exceptional circumstances of war.(9)

All evidentiary standards applied by the Commission, along with the general rule on the burden of proof, are summarized in Article 35 of the rovisional Rules for Claims Procedure:

- “1) Each claimant is responsible for submitting documents and other evidence which demonstrate satisfactorily that a particular claim or group of claims is eligible for compensation pursuant to Security Council resolution 687 (1991). Each panel will determine the admissibility, relevance, materiality and weight of any documents and other evidence submitted.

- 2) With respect to claims received under the Criteria for ExpeditedProcessing of Urgent Claims (S/AC.26/1991/1), the following guidelines will apply:

- a) For the payment of fixed amounts in the case of departures, claimants are required to provide simple documentation of the fact and date of departure from Iraq or Kuwait. Documentation of the actual amount of loss will not be required.

- b) For the payment of fixed amounts in the case of serious personal injury not resulting in deathclaimants are required to provide simple documentation of the fact and date of the injury; in the case of death, claimants are required to provide simple documentation of the death and family relationship. Documentation of the actual amount of loss will not be required.

- c) For consideration of claims up to US$ 100,000 of actual losses, such claims must be documented by appropriate evidence of the circumstances and amount of the claimed loss. Documents and other evidence required will be the reasonable minimum that is appropriate under the particular circumstances of the case. A lesser degree of documentary evidence ordinarily will be sufficient for smaller claims such as those below US$ 20,000.

- 3) With respect to claims received under the Criteria for Processing Claims of Individuals not Otherwise Covered, Claims of Corporations and Other Entities, and Claims of Governments and International Organizations (S/AC. 26/1991/7/Rev. 1) such claims must be supported by documentary and other appropriate evidence sufficient to demonstrate the circumstances and amount of the claimed loss.

A panel of Commissioners may request evidence required under this Article”

Thus, the diversified approach to evidentiary standards in the Commission's practice involved the application of three different standards of proof:

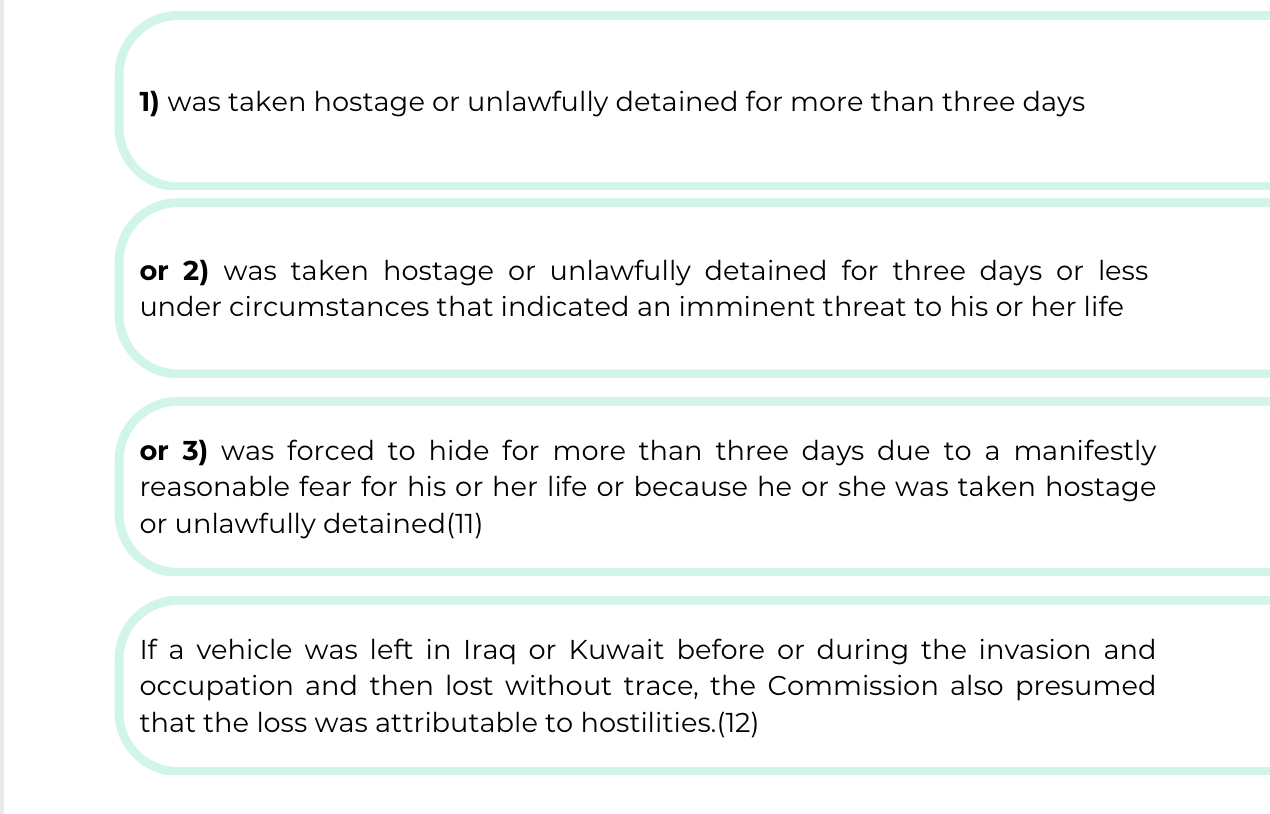

Finally, another aspect that eased the burden placed on claimants was the use of presumptions, i.e. assertions accepted by the Commission as a given without the need for proof by the claimant. Presumptions may relate to specific facts and may be drawn as an inference from other established facts.

For example, the Commission considered it reasonable to presume that the majority of deaths and injuries that occurred in Iraq or Kuwait between August 2, 1990 and March 2, 1991 were causally related to the invasion and occupation. (10)

The Commission also presumed the existence of non-pecuniary damage (mental pain and anguish) in cases where it was established that a person:

(6) Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Individual Claims For Serious Personal Injury or Death (Category “B” Claims), 26 May 1994, p. 34. The same see.: Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Installment of Individual Claims for Damages Up To Us$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 29.

(7) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages Up To Us$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 28.

(8) First Session of the Governing Council of the United Nations Compensation Commission. Criteria for Expedited Processing of Urgent Claims. S/AC.26/1991/1, 2 August 1991, para 12.

(9) REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS S/AC.26/1998/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Part One of the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages Above US$100,000 (CATEGORY “D” CLAIMS) 3 February 1998, para 72.

(10) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages up to US$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 110, 124.

Розділ VI

How it worked: selected examples of the evidentiary standards applied

Category «В»

In Recommendation S/AC.26/1994/1 (p. 35), the Panel noted that the circumstances prevailing in Kuwait and some neighboring countries between August 2, 1990 and March 2, 1991 made it extremely difficult for claimants to obtain contemporaneous medical records (i.e., medical records that were made immediately or shortly after the injury). In view of this, the Panel decided to accept medical documentation drawn up later on as sufficient evidence to confirm the fact of injury or trauma.

Moreover, the Panel noted that some claimants were deprived of the opportunity to obtain the necessary medical documents altogether, in particular given that the number of medical facilities and medical personnel in the country had been critically reduced during the occupation.(13)

Some were unable to obtain any documents because they were injured in the desert, while fleeing Iraq or Kuwait; others found it difficult to see a doctor for personal or cultural reasons, as in the case of sexual violence or torture.(14)

In such cases, the Board accepted other written evidence, witness testimony and, in some cases, the applicant's personal statements as sufficient evidence of the injury instead of medical documentation.

In particular, the Panel considered a number of cases in which claimants alleged that they had been detained by the Iraqi military and tortured in detention. The majority of such applicants submitted as evidence personal explanations stating that they had been detained and tortured, as well as an official document from the Kuwaiti authorities or the International Committee of the Red Cross confirming that the person had been detained. The vast majority had no medical documents certifying the consequences of torture.

The Commission's medical expert confirmed that victims of torture are often reluctant to seek medical help because they want to erase the memory of torture or may be ashamed to admit that their mental health has suffered as a result of their ordeal. In addition, some forms of torture do not leave visible physical scars. Taking into account the above, and the fact that the torture of Kuwaiti nationals in Iraqi captivity has been recognized as widespread in reports by international organizations(15), the Panel concluded that:

“that compensation should be awarded to those claimants who showed that they were tortured by Iraqi forces while in detention, even if they were not able to submit medical documentation, provided that the fact of detention has been attested to by an official authority.”(16)

A similar approach was followed with regard to claims of sexual violence. In addition to the fact that victims of sexual violence often avoid seeing physicians, a physician can potentially document traces of such violence only if the victim seeks treatment immediately after the attack. In the context of war and occupation, it is virtually impossible. As well as the practice of torture of detainees, sexual violence by the Iraqi military has been documented in reports by international organizations. In view of this, the Panel recommended that claims of sexual violence be upheld, even when such claims were based solely on circumstantial evidence.

In category "B" claims regarding the death of a family member, three circumstances were subject to verification, namely the fact of death, the family relationship between the claimant and the deceased, and the causal link between the death and the invasion. A death or burial certificate or similar document issued by an official institution (including a national authority, foreign embassy, or international organization), such as a letter informing the family of the deceased about the death, were recognized as conclusive evidence of the fact of death.

However, in a number of cases, death certificates could not be issued immediately upon death, in particular because the cause of death had to be determined by an expert, of which there were few due to the situation in the country, or because families received death certificates from the Iraqi authorities and then had to exchange them for Kuwaiti certificates. As a result, the death certificate could be issued several months after the death. The Commission accepted such certificates as proper and sufficient evidence.(17)

With regard to the causal link between the death and the invasion, a death certificate or any other official document (e.g., a police report) was considered sufficient evidence of causation if it stated the cause of death. If the death certificate did not indicate the cause of death, other documents explaining the connection between the invasion and the death were accepted as evidence. In some cases, the Panel recognized the applicant's personal statements of the connection between his injuries and the invasion as sufficient evidence, provided that the Commission's medical expert confirmed that the nature of the injury was consistent with the cause alleged by the claimant.(18)

Category «С»

As noted above, for this category of applications, the standard of proof was defined as a "reasonable minimum" of evidence appropriate under the particular circumstances of the case.

In determining what constitutes such a "reasonable minimum", the Panel compared the specific evidence submitted by the complainants with the background data at the disposal of the Panel regarding the availability, relevance and reliability of any such evidence in the context of the conditions prevailing as a result of the invasion and occupation.

The Panel also noted that the completed claim form itself can be of significant probative value, provided that it is properly completed and consistent with the background data and patterns identified in other similar claims. It is also important that the claim form contains an assurance signed by the claimant that the information contained in the claim is true.(19) This is especially relevant for persons who were held in Iraqi captivity:

“A special standard, furthermore, should apply to those "C2" claimants who have established that they have been taken hostage or otherwise detained or have been in hiding. Covered by the "C1" loss page, such events are likely to have had a deleterious effect on the health of these individuals, at the same time hampering their ability to provide evidence of their injuries. Consequently, their completion of the "C2" loss page may be viewed as sufficient proof of the fact of their injury”.(20)

While assessing the probative value of the completed claim forms, the Panel also considered the socio-economic characteristics of the claimants, such as education and income, as they helped to better understand the ability of the individual to present certain evidence and substantiate their position.

In addition, since the claims were not submitted directly to the Commission, but through governments, the evidentiary weight of the information provided in the claims had to be assessed by analyzing the national programs for processing these claims, and in particular whether the officials of the relevant state assisted the applicants in filling out the documents and whether they conducted any verification or checking of the information.

In particular, the following factors had to be taken into account:

(I) Whether claimants were required to complete their claim form at an officially designated location (e.g., national claims programme central or local office) or under the supervision of, or with assistance from, a national claims programme official;

(II) Whether the evidentiary items provided by claimants were reviewed by programme officials;

(III) The policies, procedures and standards employed by programme officials in screening, modifying or validating claims (e.g., whether programme officials requested additional information or evidence from claimants in support of claims, and what types of claims were held back due to deficiencies, and what types of deficiencies resulted in claims being held back);

(IV) The policies and procedures implemented by the national claims programme in connection with verifying the claims (e.g., the use of investigators or loss adjusters).(21)

The vast majority of claims in this category were supported by the applicant's personal statements as the main evidence. These statements described what had happened to the applicant at the time of the invasion, as well as the circumstances and extent of the damage he or she had suffered.

The Panel decided that the evidentiary weight of such statements should vary depending on the specific damage claimed:

“Thus, in the context of certain losses, for example, claims for MPA resulting from forced hiding, a claimant statement may be the best available evidence to indicate where, why and under what circumstances that person was hiding. The explanations and descriptions in such statements would add further to an assessment of the relevance, weight and credibility to be given to the statement, particularly when read in light of relevant background information. On the other hand, a personal statement provided in support of a claim for damages to real property, while relevant, may not be considered sufficient to establish the ownership of the property or the amount of the losses involved”.(22)

Many claimants submitted witness testimonies as evidence. Such testimony could either be an independent document or simply take the form of confirmation by one or more witnesses of the facts set forth in the claim. Notably, the witnesses were most often relatives and friends of the claimant. In its Report S/AC.26/1994/3, the Panel noted that the evidentiary weight of such testimony should be determined in the light of:

(I) the relationship of the witness to the person incurring the loss, bearing in mind that under hostile conditions and circumstances involving urgency, the only available witness may be a person related to the victim;

(II) general evidentiary principles relating to the quality and relevance of a witness statement, such as whether the statement indicates the bases for the witness' testimony (e.g., time, place, first hand knowledge of the events).(23)

Of course, written evidence (such as receipts, invoices, contracts; official government documents, civil status documents, bank and real estate documents; letters from relevant professionals, including physicians, insurance experts and former employers; photographs and newspaper articles) was recognized as having a high probative value.

As with the previous category of claims, the Panel also relied on general background information, including reports and statistical data prepared by national authorities, international organizations and other independent institutions, on the nature and causes of the losses occasioned by Iraq's invasion and occupation of Kuwait.

Category «D»

For this category of claims, a higher standard of proof (compared to categories A, B and C) was required, as well as consideration of each claim individually. Describing the standard, the Panel noted:

“72. The Panel is aware that international tribunals, however composed, and entrusted with the task of adjudicating a dispute between two States belonging to whatever legal system or systems, have recognized the principle that the law of evidence in international procedure is a flexible system shorn of any technical rules. 39/ The Panel is also conscious of the fact that the lack of standard international law rules of evidence and the fact that international tribunals are liberal in their approach to the admission and assessment of evidence does not waive the burden resting on claimants to demonstrate the circumstances and amount of the claimed loss. On the other hand, considering the difficult circumstances of the invasion and occupation of Kuwait by Iraq, as outlined in the Background Reports referred to above, many claimants cannot, and cannot be expected to, document all aspects of a claim. In many cases, relevant documents do not exist, have been destroyed, or were left behind by claimants who fled Kuwait or Iraq. Accordingly, the level of proof the Panel has considered appropriate is close to what has been called the “balance of probability” as distinguished from the concept of “beyond reasonable doubt” required in some jurisdictions to prove guilt in a criminal trial. Moreover, the test of “balance of probability” has to be applied having regard to the circumstances existing at the time of the invasion and loss”(24)

At the same time, when assessing the evidence in this category of claims, the Commission took into account a number of factors that affected the availability of certain evidence, in particular:

- the circumstances of the armed conflict;

- the socio-economic characteristics of the claimants;

- the predominantly cash-based nature of the Kuwaiti economy;

- the specifics of the national compensation programs through which the initial gathering of information from the claimants was carried out.

As in the previous categories, background information, i.e. general data on the events of the military conflict consolidated in reports and statements of international organizations, played an important role in assessing the credibility of claimants' statements. Thus, even the most demanding of the evidentiary standards used by the Commission remained flexible enough to take into account circumstantial evidence in the form of background data sets.

(13) Three main factors affected the availability of medical and related services during the invasion and occupation. First, there was a massive outflow of medical personnel from the country. Secondly, the closure, destruction and looting of medical facilities: by the end of the occupation, all 87 medical facilities were either closed or operating at far less than normal capacity. Thirdly, it is the restriction of access to medical facilities, in particular, because the occupation authorities have conditioned the ability to receive medical care on the exchange of a Kuwaiti passport for an Iraqi one, established curfews and priority treatment for the Iraqi military.

(14) Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Individual Claims For Serious Personal Injury or Death (Category “B” Claims), 26 May 1994, p. 36..

(16) Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Individual Claims For Serious Personal Injury or Death (Category “B” Claims), 26 May 1994, p. 37.

(17) Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Individual Claims For Serious Personal Injury or Death (Category “B” Claims), 26 May 1994, p. 39-40

(18) Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Individual Claims For Serious Personal Injury or Death (Category “B” Claims), 26 May 1994, p. 41.

(19) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages up to US$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 24.

(20) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages up to US$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 110.

(21) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages up to US$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 28.

(22) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages up to US$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 25-26

(23) Report and Recommendations S/AC.26/1994/3 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages up to US$100,000 (CATEGORY "C" CLAIMS), 21 December 1994, p. 26.

(24) REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS S/AC.26/1998/1 made by the Panel of Commissioners Concerning Part One of the First Instalment of Individual Claims for Damages Above US$100,000 (CATEGORY “D” CLAIMS) 3 February 1998, para 72.

Conclusions

In the extraordinary conditions of armed conflict and occupation, collecting evidence of injury is considerably more difficult for victims. There are many various reasons for that.

First of all, documenting the events unfolding around is not the first priority of people facing imminent danger.

Secondly, the nature of the undergone experience is often such that victims may consciously or unconsciously avoid any actions that remind them of the horrific past.

Thirdly, official certification of certain facts ususlly made by state bodies or other institutions (including medical institutions) may prove impossible or close to impossible due to malfunctions of such bodies and institutions, loss of control over a part of the territory by the state, physical destruction or loss of archives, registers, etc.

All of these circumstances call for special attention from international compensation mechanisms, which cannot afford the rigid approach and strict formalism characteristic of ordinary proceedings in national courts.

For this reason, the law of evidence in this area is flexible and sensitive to the special circumstances in which claimants find themselves. It is reflected in the special, lowered standards of proof employed in international compensation mechanisms. Diversification of the standards of proof in the practice of the UN Compensation Commission consisted of applying three different approaches to different categories of claims.

One approach was that claimants had to prove only the damage and its connection to the invasion without the need to provide any evidence of the amount of damage.

The second was that the amount of damage had to be proved by a "reasonable minimum" of evidence appropriate to the circumstances of the case.

Finally, the third standard, reminiscent of the civil law standard of "preponderance of the evidence", required applicants to submit "documentary and other appropriate evidence sufficient to demonstrate the circumstances and extent of the damage suffered."

However, even this standard was subject to adjustment for the special context of war.

In addition, the burden placed on claimants was eased by presumptions that were developed in the Commission's case law.

The approaches pioneered by the UN Compensation Commission should be utilized and developed within the framework of an international compensation mechanism for Ukraine.

First of all, it is the revolving human-centered approach and prioritization of individual claims of injured natural persons.

Secondly, it seems to be a productive idea to introduce two different tracks for processing claims - regular and expedited (fast-track), with the same damage being claimed in both tracks, so that while a person is waiting for his or her claim to be considered in the regular track, he or she can receive interim, fast-track compensation for at least part of the damage suffered.

Ultimately, the approach to the standards of proof in compensation mechanisms dealing with war and mass harm incidents cannot be anything other than flexible and sensitive to the special circumstances of the harmful events.

The burden of proof imposed on victims of war should not become an excessive, unbearable weight - it should be tailored flexibly to the conditions in which victims find themselves and to the realities of wartime that limit the ability to collect and present evidence.

The Institute of Legislative Ideas is an independent think tank that studies the implementation of anti-corruption policy in Ukraine and its compliance with international anti-corruption standards. We analyze the asset recovery mechanism and explore the opportunities for its improvement and extension. Today, we consider it one of the primary tasks to ensure compensation for the damage caused by the Russian aggression against Ukraine at the expense of Russian assets.