>

Аналітики>

Сivil forfeiture of unjustified assets through the prism of property rights protectionСivil forfeiture of unjustified assets through the prism of property rights protection

*This analytics is published in English only

UDC 347.952.1/.2:347.77

Ц579

Tetiana Khutor. ; Civil forfeiture of unjustified assets through the prism of property rights protection. — Kyiv: LLC RED ZET, 2020. — 24p.

ISBN 978-966-97673-9-4

Editors: Science Editor: Oksana Nesterenko. Literary Editor: Nataliia Minko. DTP Professional: LLC RED ZET.

© Tetiana Khutor – PhD candidate on the topic за темою «Civil forfeiture of unjustified assets through the prism of property rights protection», Head of the “Institute of Legislative Ideas ”think tank.

© Anti-Corruption Research and Education Centre at NaUKMA. All rights reserved.

This scientific study is devoted to the study of the Ukrainian model of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets, in particular the issue of ensuring the protection of property rights through the prism of international standards and best practice. The results of this research will be included in the dissertation carried out by Tetiana Khutor.

This report is issued within the hink ank Development nitiative for kraine, implemented by the International Renaissance Foundation in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE) with financial support from the Embassy of Sweden to Ukraine. The opinions and content expressed in this Policy Brief are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Embassy of Sweden to Ukraine, the International Renaissance Foundation and the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE)

Introduction

The news of the US Department of Justice’s claims for the civil forfeiture of assets from a company associated with the Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky in the amount of $70 million, which were illegally withdrawn from the Ukrainian PrivatBank, spread around the world’s most influential media1 . Although his activities have been investigated both in Ukraine and abroad, no country has yet issued convictions. So, on what basis does the US demand the confiscation of his property? US law2 provides an opportunity to file a claim for the confiscation of any assets related to a crime without waiting for a court conviction.

Almost a year ago, the Ukrainian parliament passed a new law3 reflecting the idea of civil forfeiture without a court conviction. At the same time, most of the controversy concerned the possible violation of human rights, in particular the unjustified restriction of property rights.

In this regard, this study is intended to answer an analytical question: what is the Ukrainian model of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets and does it provide protection of property rights through the prism of international standards and the best practices?

The methodological basis of the research is the analysis of legislative acts (Ukrainian, foreign and international): case studies when analyzing decisions of national courts, key decisions of the ECHR and national constitutional courts in terms of civil forfeiture of assets without a conviction by the court; analysis of approaches in the legal literature as well as positions, views, proposals for developing the foundations of civil forfeiture. The method of interviews to obtain opinions and positions of representatives of law enforcement and other state bodies regarding the practice of application and effectiveness of the institution of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets has also been used in the research.

This policy paper is based on a broad study and largely reflects its second part on the Ukrainian model of civil forfeiture. The full version of the study, which is available by the link, contains a more detailed analysis, in particular, of international regulations, foreign models of civil forfeiture in the US, the UK, Colombia, the EU.

Section І

Civil forfeiture of unjustified assets without a ourt onvition: orld pratie and property rights

1.1 Briefly about the prerequisites for the introdution of civil confisation without a court conviction

Civil forfeiture without a court conviction is an effective tool in the hands of law enforcement officers, which in world practice is considered an effective tool, including the fight against corruption4 , 5 . Various countries use it to simplify the process of returning illegally acquired property, not limited to lengthy and complex procedures within the framework of the criminal process. At the same time, the list of crimes, as a result of which such assets were obtained, and which can be confiscated in a simplified civil procedure, varies from country to country: from a very wide range (from theft to transnational money laundering – like in the USA), to very narrow (conditional linking only to illegal enrichment (as in Ukraine).

However, the reasons for the effectiveness of civil forfeiture without a conviction are common to all:

a) the standard of proof is established at the level of “preponderance of evidence”, instead of the criminal one – “beyond reasonable doubt”, which provides that “any doubt shall be interpreted in favor of the accused”;

b) a dynamic burden of proving guilt has been established – the defense side is deprived of the right not to testify against themselves or their relatives and friends, because the refutationof the unfoundedness of assets is imposed on the defendant;

c) the ability to confiscate property, even if:

• it is impossible to open criminal proceedings for procedural or technical reasons;

• criminal proceedings are closed;

• criminal proceedings are open, but the evidence confirming that the income were obtained illegally is not enough for a criminal standard of proof “beyond reasonable doubt”;

• the national legislation complicates the procedure of investigation in relation to certain categories of persons, such as members of parliament, judges, etc;

• the suspect is endowed with great power and has the ability to pressure witnesses, destroy evidence of a crime, etc.

Usually, the process of civil confiscation outside criminal proceedings can be conditionally divided into 4 stages: 1) gathering of evidence; 2) seizure of assets; 3) the trial phase, when the gathering of evidence is completed and directed to trial, at which the court determines whether sufficient convincing evidence has been provided and whether the rule of law was respected at the first stage; 4) confiscation of property6 .

The Ukrainian model of civil forfeiture, as noted, is associated exclusively with the institution of illicit enrichment and, in fact, is a “procedural-facilitated” version. Thus, the adoption of the law on the civil forfeiture of unjustified assets in Ukraine at the end of 2019 was due to the need to bring to justice the persons whose proceedings were closed as a result of the recognition of the provisions of the criminal law regulating the crime of illegal enrichment unconstitutional7 and the impossibility to do so due to the principle of irreversibility of the law in time. And there were 65 such industries, 27 of which had to be closed completely, and 38 – partially. The amount of assets, the legality of which was being investigated, reached half a billion hryvnias8.

Such a move is neither extreme, nor unexpected. Indeed, firstly, civil forfeiture in world practice is considered an effective tool in the fight against corruption9 , 10. Secondly, as the Colombian Constitutional Court rightly noted, the concept of illicit enrichment is much broader than the concept of a criminal offense – it does not fit within the framework of criminal law and goes into the sphere of property law; and its purpose is not only to impose punishment on the offender, but to deprive the offender of ownership of assets obtained as a result of illegal actions11.

1.2. International regulation and key elements of foreign models (US, UK, Columbia, EU)

Unjustified/corrupt assets are often located in other jurisdictions and the ability to obtain international assistance is an extremely important element of their confiscation. At the same time, in response to previous attempts by Ukraine to impose civil forfeiture, the US Department of Justice has officially warned that Ukraine will not be able to seize foreign property if legislative provisions do not comply with world practice of special confiscation and international principles of democracy and human rights12.

Quite often, the success of the civil forfeiture mechanism is kinked to the experience of Western democracies such as the United States and Great Britain13.

Indeed, historically, the concept of asset confiscation outside of criminal proceedings originated in the countries of the Anglo-Saxon legal system and is based on the idea that if a “thing” breaks the law, the state has the right to confiscate it. In the United States, civil forfeiture/non-conviction based forfeiture laws apply to two categories of property: proceeds of crime and instrumentalities. That is, the proof of the connection between property and criminal activity is a mandatory component. For example, the already mentioned civil lawsuits for the confiscation of two commercial real estate objects acquired with funds withdrawn from Privatbank14 are based on the links with the money laundering crimes under investigation. At the same time, unlike in Ukraine, the civil forfeiture of unfounded assets as a purely anti-corruption mechanism directed against unscrupulous American officials is not established in the USA.

The UK, thanks to relatively recent changes in the legislation in 2018, introduced a special institution of civil confiscation without a court conviction – unexplained wealth order (UWO), – which differs from the American one and is intended to oblige a person to explain the origin of their property. First, the civil procedure is initiated in personam – against the person who owns the asset, and not in rem – against the asset. Secondly, state authorities should not prove the connection of property with a predicative offense. Third, the court decides on the basis of the principle of “evidence preference” that the assets were obtained from unknown sources, without specifying which crime/other illegal action was the source of the proceeds. Fourth, it is the UWO that transfers the burden of proof from the state to the owner of the property, who must prove that the asset’s origin is legal15.

Despite the pessimistic forecasts, now this institution is actively working16. With regard to possible infringement of property rights, the British court has already ruled17 that the intervention takes place only in case of loss of the value of the asset. And since the requirement to simply explain the legality of its origin does not in any way affect its value, there is no violation of Article 1 of Protocol 1 (right to property) (see paragraphs 98–100 of the National Crime Agency v Zamira Hajiyeva decision).

It is important to understand the effectiveness of the application of this mechanism not only in developed countries, but also in developing countries18. Colombia ranks 96th in the Corruption Perceptions Index, Ukraine is 126th, and the United Kingdom and the United States are 23rd and 12th respectively.19The civil confiscation model of unfounded assets in Colombia, like the UK, pursues the same goals as Ukrainian law. At the same time, Colombia will better illustrate the difficulties that Ukraine can face in implementing similar legislation.

Colombian civil forfeiture model exists alongside the legally criminalized illicit enrichment. While the most comprehensive and detailed of its kind in Latin America20, the law did not work well in practice, as the process became lengthy and complicated due to many appeals of both evidence and decisions21. Insufficient staffing in the prosecutor’s office, corruption in local investigative bodies and unwillingness to cooperate with prosecutors, unclear data in registers (especially land registers), imperfect asset management22 and even destruction of documents – all this prevented the effective implementation of the law23.

In terms of respecting property rights, the Colombian Constitutional Court determined that in matters of conflict of private and public interest, the latter should be preferred, because the legal system protects the rightful owner, and the purpose of the law is to hold down the results of illegal activities24.

The practice of European countries also provides for many different approaches to civil confiscation, with most countries enshrining the American model in their legislation.

General European standards that rely upon states to protect property owners’ rights during civil forfeiture without conviction are best reflected in the practice of the European Court of Human Rights.

When considering complaints in the application of confiscation, the European Court of Human Rights formulated an approach according to which the compliance of national law with Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the European Convention on Human Rights is determined, which essentially guarantees the right of individuals to peaceful possession of their property and the right of the state to exercise control over the use of property in accordance with the general interest25.

The ECHR’s approach is to provide answers to the following questions: 1) Is the confiscation legal, that is, is it provided for by the national law? 2) Is there a legitimate aim being pursued? 3) Are the measures applied (in our case – confiscation) proportional to achieve this goal?

With the answers to the first 2 questions, difficulties almost never arise. So, firstly, if confiscation is provided for in the law clearly and comprehensively, it is considered legal. Secondly, if the confiscation was applied regardless of the existence of a criminal charge and is rather the result of a separate “civil” judicial proceeding, the purpose of which is to return property acquired illegally, such a measure qualifies as state control over the use of property in the sense of the second paragraph of Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the Convention26. After all, confiscation in the case of combating corruption is carried out in accordance with the general interest, so that the use of property is not a benefit for its illegal owners and does not harm the society.

Regarding the third question (in terms of proportionality) the situation is somewhat more complicated, since the court requires that a “fair balance” be sought between the general needs of society and the requirements for the protection of fundamental human rights. Although, in general, there are not many cases where the Court has found the interference with property rights disproportionate, according to the researchers, this is due to the lack of clear criteria for the disproportionateness of such interference and the procedural nature of the requirements that the Court puts forward to domestic law27. Most often, the Court approves a confiscation if it28:

a) is part of comprehensive national strategies to combat serious crimes, b) defendants in such cases should be provided with a reasonable opportunity to prove their own arguments in national courts, both in writing and orally, c) hearings are held in a competitive manner, d) evidence together with supporting documents are dealt with properly.

Perhaps the greatest criticism is caused by the possibility of confiscation of property from persons who are not actually involved in the commission of any crimes that led to the acquisition of the disputed assets, are not officials who may be suspected of corruption, and are not members of their families. At the same time, the purpose of civil forfeiture is not to punish persons, but to confiscate property obtained by illegal means.

The guidelines for the application of Article 1 of Protocol 1 of the ECHR (protection of property rights) state that the ECHR provides the authorities with the opportunity to apply confiscation measures, including from any persons who were believed to have owned and disposed of illegally obtained property on behalf of suspected offenders, or any others without bona fide acquirer status (Raimondo v. Italy; Arcuri and Others v. Italy; Morabito and Others v. Italy; Butler v. the United Kingdom; Webb v. the United Kingdom; Saccoccia v. Austria; Silickienė v. Lithuania)29.

Similar requirements are enshrined in the legislation of the countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia OECD30, 31. A similar approach is used by US judges, which they call “retroactive law” (used in United States v. Lazarenko32) and which stipulates that the state is deemed as the real owner of the confiscated property at the time of the illegal actions. Therefore, if the property was transferred to the ownership of another person, it is still subject to confiscation, unless the new owner provides evidence that the property was acquired by him as a result of a good faith transaction on a reimbursable basis and does not prove that he did not know that the property is subject to confiscation.

Thus, in accordance with international standards, third parties from whom property may be confiscated include: 1) nominal owners – any third parties, and not only family members or close persons who owned and disposed of illegally obtained property on behalf of the suspects; 2) unscrupulous acquisitors.

Thus, as a general rule, civil forfeiture of assets outside criminal proceedings is not recognized by the ECHR as a violation of property rights, if the state adheres to the principles of legality, legitimacy and proportionality and in practice ensures the procedural rights33 of asset owners.

Section ІІ

Civil forfeiture of unjustified assets: a comprehensive analysis of the Ukrainian model

2.1 revious attempts to introdue ivil forfeiture of unfounded assets in Ukraine

There have been attempts to introduce a prototype of civil forfeiture in Ukraine without a court conviction on more than one occasion, starting in 2015. A number of bills were initiated by both the government and individual members of the Parliament, which proposed to confiscate the property of officials without a preliminary court verdict. In some cases, the confiscation had to take place immediately at the initiative of the prosecutor’s office with the possibility of further appeal by the owners, but in other cases there is a risk for bona fide acquirers. But all the initiatives met with stiff resistance from the public34, 35, the Parliament36, 37, and international partners38. The reason is that the proposed legislation did not comply with the world practice of special confiscation and international principles of democracy and respect for human rights, in particular, the lack of protection of the procedural rights of asset owners39.

2.2 eneral harateristis and analysis of the urrent edition of the provisions on ivil forfeiture of unjustified assets

At the end of 2019, a new version of the law was adopted, introducing a completely new institution for the Ukrainian legislation of civil forfeiture of unfounded assets without a court conviction.

The purpose of the Ukrainian model is to return illegally obtained assets and deprive a person of the right to public service or positions in local government.

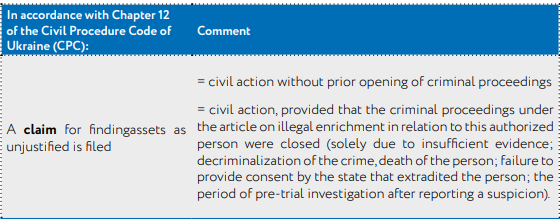

Civil forfeiture of unjustified assets is as follows:

A) Subject of proving

What must be proven by law enforcement to file a claim?

The authority “to take measures to identify unjustified assets and collect evidence of their unjustifiedness” is vested in NABU, SAP and, in limited cases, the State Bureau of Investigation and the GPU.

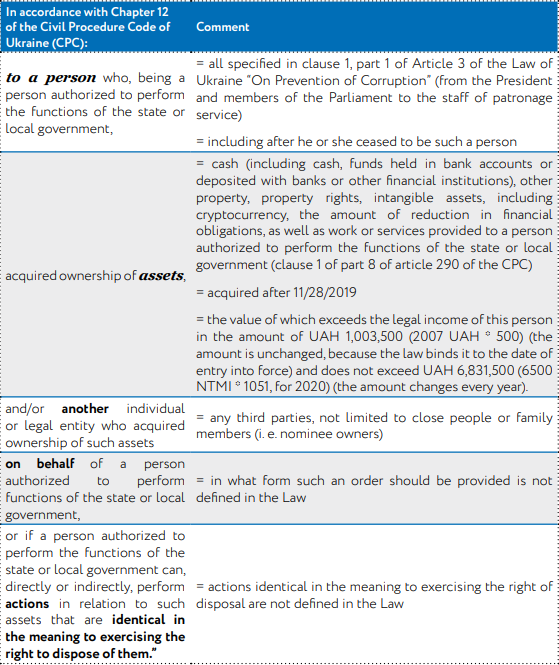

The law imposes on law enforcement officers the obligation to provide factual data on (Article 81 of the Code of Civil Procedure): 1. the relationship between assets and the authorized person: both direct (the authorized person de jure acquired the property in his/her ownership) and indirect (the authorized person de facto acquired the property in ownership, but de jure the ownership right belongs to third parties)

2. unjustifiedness of such assets.

The unjustifiedness of assets is determined by the difference between the value of the assets and all legal income and savings. If the difference between them is more than UAH 1 million, the assets are considered unjustified and subject to confiscation. (more in the next section)

What must be proved by the court in order to find the assets to be unjustified?

This category of cases, as a general rule, falls within the jurisdiction of the Supreme AntiCorruption Court.

Unlike the requirements presented at the initial stage – filing a claim, the court deems assets as unjustified if “the court, on the basis of the evidence presented, has not established that the assets or funds necessary to acquire the assets for which a claim was filed to declare them unjustified were acquired at the expense of legal income” (Art. 291 CPC).

Thus, on the one hand, it imposes on the defendant the obligation to refute more than has been proven by the plaintiff. On the other hand, this indicates that the legislator imposed on the defendant the obligation to explain the sources of his/her income, received also before the entry into force of the law, through which the disputed assets were acquired, while not providing the opportunity to confiscate such assets, even if they are not provided evidence of the legality of their acquisition. Therefore, without risking to violate the principle of the irreversibility of the law in time, such a norm does not allow deeming assets received before the entry into force of the law as unjustified, at the same time creating a safeguard for their use as legalization of the acquisition of unjustified assets already during the law.

Thus, control over the legality of the acquisition of property by authorized persons who took office and/or received property before the entry into force of the Law (November 28, 2019) may become especially problematic. For example, there is already a practice of a member of Parliament declaring millions of hryvnias received as gifts from parents40, which were received before the entry into force of the relevant law in 2018. In this context, the Law does not define the time frame for such “partially reverse” operation of the law in time.

In this regard, the practice of the courts’ application of this provision and the limits of retroactivity of the law are very important.

The experience of other countries shows that avoiding the retrospective effect of the law is not a common practice, because this way there is a significant reduction in the range of assets that can be punished. Moreover, the effect of the introduction of such norms is delayed for years. For example, the UK, introducing the relevant legislation, clearly provided that the law applies to all property, regardless of whether such property was acquired before the entry into force of this law or after that.

B) “Unjustifiedness of assets” and “connection with an official” as key elements of confiscation

Unjustifiedness of assets as 1 of the 2 key elements of confiscation

The unjustifiedness of assets is determined by the difference between the value of the assets and all legal income and savings:

Analysis of the provisions of the Ukrainian Law indicates that the legislator has established a fairly loyal approach to the procedure for calculating the unjustifiedness of assets, because:

- costs are not included in this formula. That is, neither the costs of maintaining the property, nor the costs associated with the life of the authorized person and his/her family, in particular, which will be carried out in cash, should not be taken into account to reduce income

- the formula includes current savings both in non-cash and in cash (clause 8, part 1, article 46 of the Law of Ukraine “On Preventing Corruption”). Taking into account that the amount of available cash is not subject to verification, non-existent declared cash savings before taking office may become a “legal cushion” for legalizing illegally obtained assets in the future. A safeguard against such abuse may be the provision on the defendant’s obligation to substantiate the legality of the proceeds that were used to acquire the disputed assets. At the same time, the Law does not stipulate whether a person is obliged to substantiate the legality of income received prior to the obtaining of the status of an authorized person;

- the law provides for a nonexhaustive list of sources of income that are considered legal: “income of the subject of declaration or members of his/her family, including income in the form of wages ... and other income” 41. Other income can include winnings, inheritance and any other income (including pre-trial settlement of disputes) that can be described as legitimate. In addition, income is considered legal in form of “monetary assets available to the declarant or members of his/her family, including cash ... funds lent to third parties, as well as assets in precious (banking) metals”42. Such income must be obtained legally. The amount of legal income available for the legitimate receipt by the declarant is limited by the prohibition to engage in other paid activities (except for teaching, scientific and creative activities, medical practice, instructor and judicial practice in sports)43. At the same time, family members do not have such restrictions.

Connection of assets with an official as 2 of 2 key elements of confiscation

The connection between an official and an asset can exist in 2 forms – direct and indirect. The first one is proved by legal confirmation of the official’s ownership of certain assets. The second is proves by confirming the official’s control over the asset, regardless of who is the legal owner of the asset.

Unlike the experience of most other countries, which were described above, the Ukrainian law on civil forfeiture requires proving the connection of an asset with an official, and not with a crime committed by him/her.

At the same time, unlike the same UK legislation, which is similar in purpose to the Ukrainian, the latter does not require proof of whether the third party, who formally/ informally owns the disputed asset, had the financial ability to acquire it. At the same time, law enforcement officers must prove, and the official refute, that such property is associated with the official.

First, the law is not tied to family members or close persons, and that makes it possible to expand the range of such entities, who can not be limited only to individuals.

Second, unlike the legislation of many other countries, which were described above, Ukrainian lawmakers abandoned the construction of “transfer of assets” to another person. In fact, as the practice of applying the previous version of the article on illegal enrichment has shown, law enforcement agencies could not prove such a “transfer” in cases where assets or funds for the acquisition of such assets did not “pass” through the main entity, but were directly transferred from third parties to other third parties.

Therefore, the law provides for all cases when a person is the actual controller of these assets – either he/she has given an “order” to a third party to acquire the asset, or he/she can perform actions in relation to assets that are identical to the right of disposal.

C) Procedural guarantees designed to protect the rights of legal owners

Despite the clear advantages of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets outside the criminal process, the deprivation of a number of procedural guarantees caused a lot of concern among members of the Ukrainian Parliament44 and lawyers45 regarding possible violation of property rights, including third parties.

First of all, in contrast to the classical civil proceedings in rem (that is, against property), which is used by most countries, Ukraine chose a different path and identified the legal owners of property as the defendant in such cases. This approach is recognized as justified, because civil forfeiture in personam (against the person) turns out to be especially useful for the return of income from corruption and theft of state assets46, since it begins with an inspection of a specific subject. This makes it impossible to fail to inform about the beginning of the relevant procedure, since a claim is filed against the legal owner of the property, and all interested parties must be notified, and persons whose rights may be violated must be involved as third parties who do not declare independent claims (which, according to Art. 43 of the CPC have all the rights of the participants in the case from providing evidence to appealing the decision).

D) Proving in the process of deeming assets as unjustified

The law has defined the standard of proof – the advantage of a body of evidence that is more convincing. In fact, it is about the “preponderance of the evidence”, in which the burden of proof is fulfilled when it is proved that the subjective probability that a controversial fact took place exceeds the probability of the opposite47. The law does not directly define this, but “preponderance of evidence” usually means that the assumption is rather true than false, that is, the probability of its being true is more than 50%48.

The use of this standard of proof instead of the criminal “beyond reasonable doubt” (or “deep conviction”) is often criticized by persons whose property is subject to confiscation. At the same time, both the domestic courts and the ECHR in their decisions49 argue that its application is justified in cases where the confiscation process takes place in the framework of civil proceedings.

Applying the ngel three-way test: 1) classification of this issue in national legislation; 2) the nature of the violation that is put forward against the person; and 3) the seriousness of what is at stake or the nature of the penalty applied50, the Northern Ireland court has concluded that such cases are civil in nature, as they do not aim to impose any penalty other than the recovery of assets that do not legally belong to the person51. Therefore, the application of the stricter standard of proof that applies in criminal proceedings is not mandatory.

Moreover, cases of unjustified assets are characterized by the reluctance of one of the parties to present evidence that is important for the decision. In such cases, the ECHR itself considered it necessary to deviate from the standard “beyond reasonable doubt”52, 53.

The Civil Procedure Code does not contain special requirements for evidence that must be provided by either the prosecution or the defense. Evidence that, according to the general rule (Chapter 5 of the Civil Procedure Code), is used in civil proceedings, should also be used in cases on the deemong of assets as unjustified. During the recent legal reform, the institution of proof in civil proceedings has undergone significant changes that directly affect the quality of proving in cases on the recognition of assets as unjustified.

The obligations of the parties, among other things, include the presentation of all the evidence they have in the manner and within the time limits established by law or the court, not to hide the evidence (paragraph 4 of part 2 of article 43 of the Civil Procedure Code). This principle is very important in the context of the concealment of evidence, because it is natural that both law enforcement agencies and the defendant’s side will try to highlight only facts that support the claims or refute them. The preservation of such a balance should be ensured by the gathering of evidence by the court on its own initiative, if it doubts the good faith exercise by the participants in the case of their procedural rights or the performance of duties on evidence (part 2 of article 13, part 7 of article 81 of the Civil Procedure Code).

The above described is designed to maintain a balance between the adversarial nature of the parties, ensures the implementation of private law interests in civil proceedings and the activity of the court in the context of the principle of judicial leadership of the process, which reflects the public law interest in the effectiveness of civil proceedings and its task – fair, impartial and timely consideration and resolution of civil cases with the purpose of effective protection of violated, unrecognized or disputed rights, freedoms or interests of individuals, the rights and interests of legal entities, the interests of the state (part 1 of article 2 of the Civil Procedure Code)54.

Among the shortcomings, it is necessary to point out that the law does not give a clear answer, whether the evidence collected in the framework of criminal proceedings can be used and to what extent. In addition, the law does not explain at what stage, by what criteria and in what form the court determines the sufficiency of the evidence presented by the law enforcement agencies of the unjustifiedness of the acquired assets to shift the burden of proving the legality of the sources of the assets to the defendant.

E) Extended confiscation

The value-based approach to confiscation – that is, the fixed opportunity to confiscate property equivalent to the value of illegally obtained assets – is a positive global practice, since otherwise the loss of an asset (including for reasons beyond the control of the owner) would result in the impossibility of confiscating nothing else. At the same time, Part 3 of Art. 292 of the CPC established that in case of impossibility of foreclosure on assets deemed as unjustified, it is the defendant who is obliged to pay the cost of such assets, or the recovery applies to other assets of the defendant, corresponding to the value of the unjustified assets. Given the fact that the defendant, in accordance with Part 4 of Art. 290 Code CPC can be any other person, the foreclosure on his/her assets that are not deemed as unjustified, that is, related to an authorized person, may be disproportionate. Indeed, given that the main element for the confiscation of an asset from a nominal owner is the connection of the disputed asset with an official, a third party who does not actually dispose of the disputed assets should not be held liable with his/her property for the actions of the official. On the other hand, such a provision can serve as a cover for officials from the risk of confiscation of their own assets due to the absence of any other property of the “nominees”. In this regard, if it is proven that the real owner of the asset is an official, the extended confiscation should primarily apply to his/her assets, and not to the assets of third parties.

F) Seizure of assets and rights of owners

The law provides for the ability to seize assets, including without the knowledge of the owners by a court decision. A safeguard against abuse is that in the application for securing a claim by seizing assets, sufficient data must be provided to allow the assets to be considered unjustified. If such an application for securing a claim raises the issue of its consideration without notifying the defendant, it must also provide a proper justification for such a need. Despite the high degree of opposition in parliament on this norm as violating the rights of third parties, this approach is a good international practice55.

At the same time, the issue of the seizure of assets in civil confiscation is essential in the practice of the ECHR. The textbook case is Raimondo v. Italy56, in which the ECHR determined that the arrest itself does not violate Article 1 of Protocol 1 of the Convention and does not violate the principle of proportionality, because the aim is not to deprive the applicant of property, but to prevent its use, and to ensure the safety property for the possibility of further confiscation, if necessary. Failure to comply with the procedural rights of property owners during the implementation of the arrest may become the basis for the recognition of the arrest as violating the property right57.

The transfer of seized assets to a professional manager is the global best practice to ensure that assets and their economic value are preserved. Therefore, the provision according to which the property58 is transferred to ARMA for management is aimed at increasing the efficiency of the arrest. An additional guarantee is that the court is obliged to consider this issue at the hearing with the notification of the defendant.

At the same time, one should take into account the fact that ARMA has the authority to manage assets, which does not include the possibility of storage, but only the transfer of property to other persons for management and sale. Any property that has been seized in criminal proceedings or in lawsuits for deeming assets as unjustified and their reclamation is subject to sale, provided that it belongs to one or more types of property defined in the Model List of Property, the storage of which is impossible without unnecessary difficulties59. At the same time, this list is not exhaustive; individual criteria for classifying assets as such property are very general and evaluative60.

ARMA has repeatedly been accused of non-transparent and poor-quality asset management. For example, both journalists and the Minister of Justice claim specific abuses due to the lack of authority to store and sell at reduced prices (by 10–50 times)61, 62.

In this regard, the activity of ARMA as a manager of seized property may contribute to the violation of the rights of the owners of the disputed assets. Therefore, in order to avoid abuse, ARMA must be empowered with the authority to store assets. In addition, the possibility of selling the asset without the consent of the owner needs to be reconsidered. And most importantly, it is necessary to change the practice of ARMA to ensure high-quality management of seized assets. Indeed, in the absence of the latter and taking into account the above-mentioned practice of the ECHR, the issue of violation of the rights of owners of assets will be very acute.

G) Features of confiscation from nominal owners

Many countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan and others) have difficulties with the confiscation of assets from nominal owners63. Ukrainian law provides that civil confiscation will only concern unjustified assets directly or indirectly owned by persons authorized to perform the functions of the state or local government (hereinafter – the authorized person).

Assets are owned indirectly if third parties

- acquired them “on behalf” of an authorized person;

- the authorized person can, directly or indirectly, perform actions in relation to such assets that are identical in the meaning to exercising the right to dispose of them.

Criticism of these provisions took place during the adoption of the law, in particular, in terms of the uncertainty of what exactly should be considered as on behalf and the actions that are identical in the meaning of the exercise of the right to dispose.

Acquisition on behalf

In the first edition of the bill, the authors suggested using the term “order”. But during the discussions in the profile committee, in particular for reasons of complexity of proof and breadth of interpretation, it was changed to “on behalf”.

After making such a decision, a risk of too narrow interpretation of this term arised. Thus, the civil legislation (section 68 of the Civil Code of Ukraine) considers an “order” as an agreement under which one party (agent) undertakes to perform certain legal actions on behalf of and at the expense of the other party (principal). The Code does not contain a mandatory requirement for the form of the agreement. Therefore, such an agreement is not prohibited to be made both orally and in writing.

At the same time, Article 1007 of the Civil Code of Ukraine obliges the principal to issue a power of attorney, which is made in writing regardless of the form of the contract of agency. And the last, in accordance with Part 3 of Art. 244 of the Civil Code must be written and correspond to the form in which the legal action is performed, for which the principal authorizes the agent (part 3 of article 244, part 1 of article 245 of the Civil Procedure Code). That is, the question is the actions for the acquisition of assets – the overwhelming majority of which requires making of an agreement not only in writing, but also with notarization (the right to dispose of real estate, management and disposal of corporate rights, use and disposal of vehicles) – the power of attorney must be also in written form and notarized.

Hopefully, the judges will not use the formal approach to the interpretation of the term “on behalf” described above. After all, usually, as the analyzed judicial practice shows64, if a person aims to hide illegally obtained income, it is unlikely that he/she will use the written form of the contract65. And it is almost impossible to prove the existence of an oral contract if both parties deny the fact of its existence.

Therefore, taking into account the intention of the legislators when adopting this provision, the term “on dehalf” should be understood in a broad sense and not reduced to an agreement that is used by the Civil Code of Ukraine.

Actions identical in the meaning to exercising the right of disposal

This reason was perceived ambiguously, in particular, due to a lack of understanding which actions should be considered identical to the right of disposal. At the same time, this legal structure is not new in anti-corruption legislation. So, part 3 of Art. 46 of the Law of Ukraine “On the Prevention of Corruption” provides for the obligation of the declarants to enter information about the objects in the declaration if the declarant or a member of his/her family can perform actions in relation to such an object that are identical in the meaning of exercising the right to dispose of it.

The interpretation of “actions that are identical in the meaning to the right of disposal” was carried out by the National Agency for the Prevention of Corruption in its Clarifications. The point in qiestion here is a situation when the declarant or a member of his/her family controls certain property through an unformalized right to dispose of it through the actual possibility of determining the fate of this property. The Clarification provides examples: “a third party purchased a vehicle at the expense of the declarant. At the same time, although the vehicle is owned by a third party, but the declarant has the opportunity to use it at its own discretion or to direct a third party to sell it at any time66.” It is also emphasized that the possibility of control over the property of a third party must be justified, that is, exclude cases when the third party is the real owner of the property and acts of its own free will (on its own initiative) in the interests of the declarant. When determining whether a third party is the real owner, one should take into account, in particular, the property status of such a person, namely, whether he/she could have acquired the relevant property, taking into account income and monetary assets67.

In practice, this condition also causes certain difficulties of proof. The analysis of the court decisions that provide for its application indicates the extreme limitation of its use.

Considering the explanations of the NACP, a telling illustration is the case of the nondeclaration by the head of the National Academy of Ground Forces named after Petro Sagaidachny of two vehicles as assets for which he could perform actions identical in the meaning of exercising the right of disposal68.

NACP found as a violation the failure to declare Lexus LX 570 and Volkswagen Passat, despite the presence of written power of attorney for the disposal of the vehicles, issuing insurance policies in its own name and crossing the border as a driver in one of the vehicles. The subject claimed that he was not aware of the existence of the powers of attorney and appealed against the NACP’s decision in court.

According to investigative journalists, the car is registered to the general’s 92-year-old mother-in-law, and the estimated cost of the car at the time was $34,00069.

At the same time, the court of both the first and the appellate instance deemed the decision of the NACP as illegal, since the actions of the declarant, in the court’s opinion, had nothing to do with the exercise of the right to dispose of it. The court noted that taking into account the “persuasiveness of the evidence”, the court believed the subject, not the NACP. The case is currently pending at the cassation instance.

In another case against a judge, the court decided that 1) a person who has a power of attorney for the right to own or use property (7 luxury cars) acquires the status of the declarant only on condition of actual possession and use of the object of declaration as of December 31 of the year of declaration, and not formal ownership of a power of attorney; 2) the power of attorney to perform a certain action to dispose of the thing makes the declarant only a representative of the owner. The court additionally substantiated this by the fact that the mother of the declarant (who is the owner of the property) independently sold this property without the participation of the declarant. Therefore, the the declarant, according to the court, in this case only performs the functions of representation by proxy, that is, acts on behalf of the owner, acting in his/her interests and not receiving profit from the disposal of the thing70.

The cited decision is no exception to the general rule. The judges narrow down and formalize the content of “actions that are identical in the meaning of the exercise of the right to dispose” and in every possible way avoid using it.

In none of the above mentioned decisions did the court assess the income of third parties and the real opportunity to acquire assets for these incomes. In addition, the court imposed the obligation on the NACP to prove that the declarant can perform actions that are identical in the meaning of the right to dispose. But taking into account the limited powers of the NACP in the framework of monitoring the lifestyle and full examination (comparing the declared assets and data in information registers) the effectiveness of such actions is minimal.

Unlike NACP, NABU, as an investigative body, has broader powers to collect evidence, including access to bank secrets. Therefore, we hope that the practice of considering cases of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets and the court’s reasoning will not be as restrictive as in cases of inaccurate declaration described above.

Therefore, he key subject in cases of civil forfeiture is the court, and it is on its understanding of these provisions that the successful implementation of the institution of civil forfeiture in Ukraine depends.

Conсlusions

Reсommendations

Сivil forfeiture is recognized worldwide as an effective mechanism to combat the acquisition and use of illegal and unjustified assets.

There are various models for its introduction. Ukraine has chosen a model that does not require either a court conviction or the opening of criminal proceedings. The chosen approach reflects the signs of the institution of “unexplained wealth orders”, which in world practice is aimed, in particular, at the confiscation of corrupt property of officials. First, due to the fact that the claim is filed against the person – the owner of the asset in personam, and not against the asset itself in rem (classic for the institution of civil forfeiture), the investigation and gathering of evidence is greatly simplified, and at the level of law enforcement, the proof of proportionality of the confiscation will not cause questions. Second, state authorities should not prove the connection of property with a predicative offense. In confiscation in the framework of criminal proceedings, the state is obliged to prove that the property is either the object or the means of committing a crime. Ukrainian legislation provides for that law enforcement agencies prove, and the court decides on the basis of the principle of “preponderance of evidence” that the assets were obtained by the official from unknown sources, without specifying which crime/other illegal action was the source of the income. Third, after the court validates the evidence of the unjustifiedness of the assets provided by law enforcement agencies, the burden of proof is transferred from the state to the owner of the property, who must prove that the asset’s origin is legal. That is, in fact, it is “dynamic” burden of proof.

The model of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets without a court conviction set forth in Ukrainian legislation complies with international standards and best existing practices by providing broad procedural rights to the defendant and third parties.

The grounds for the confiscation of assets only formally owned by third parties are provided for in current legislation and provide an opportunity to cover a wide range of assets and nominees to whom they may belong.

At the same time, to ensure a fair and impartial implementation of the institution of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets, as well as to prevent further rulings of the European Court of Human Rights on human rights violations by Ukraine, we recommend that the Supreme Court and the High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine consider the possibility of implementing the following proposals:

1. to develop clarifications with a thorough interpretation of what should be understood and how to define “the actions of an official that are identical in content to the exercise of the right to dispose of assets” and “the acquisition of assets on behalf” in cases of the civil forfeiture of unjustified assets from nominee owners.

While the grounds for the confiscation of assets only formally owned by third parties are provided for in current legislation and potentially provide an opportunity to cover a wide range of assets and nominees to whom they may belong, previous cases of their interpretation by national courts indicate the use of restrictive interpretation. This, firstly, does not correspond to the goal set by the legislator, and secondly, it does not contribute to the effective implementation of this provision. The court should not limit actions that are identical to the right of disposal solely to “possession and use of the asset as of December 31,” but, when assessing the level of income of third parties, should find out whether these persons could acquire assets at their own expense as a result of a real transaction. Also, we do not recommend using a formal approach when interpreting the term “on behalf” only in the sense of a formal agreement in accordance with the requirements of the Civil Code of Ukraine. Indeed, the latter greatly complicates the proof of the existence of such an agreement.

2. Taking into account international standards and the practice of the European Court of Human Rights, in considering this category of cases, the High Anti-Corruption Court should provide the necessary procedural guarantees for the owners of the disputed assets:

• defendants in such cases should be provided with a reasonable opportunity to prove their own arguments in national courts, both in writing and orally,

• the hearings must be held in a competitive manner,

• the evidence, together with supporting documents, must be properly considered,

• seizure should only take place in accordance with the law and in cases where there is a reasonable risk to believe that the assets may be destroyed/hidden or otherwise lose their value through the fault of the owner.

3. Enshrining the civil forfeiture of unjustified assets in legislation is in line with the general principles that ensure the rights of the owner. At the same time, some details, in the absence of previous practice, require additional legal definition.

3.1. Until the relevant changes in legislation are adopted the Supreme Court should clearly define at what stage, by what criteria and in which form the court determines the sufficiency of the evidence presented by law enforcement agencies that the acquired assets are unjustified to shift the burden of proving the legality of the sources of the assets to the defendant. An additional settlement is required by the issue of admissibility of evidence, in particular, whether the evidence collected in the framework of criminal proceedings can be used, and to what extent, what evidence can be used if the criminal proceeding was not previously opened.

3.2.Until the relevant legislative changes are adopted, the Supreme Court should clarify – 1) whether a person is obliged to prove the legality of the sources of his or her income received before his or her assumption of office; 2) how “deeply” the owner should prove the origin of his or her wealth, necessary for the acquisition of the disputed assets. Actually, according to Art 291 of the Code of Civil Procedure71, the court must establish the legality of the income necessary for the acquisition of the disputed assets, but the law doesn’t specify the time limits within which such income could be obtained.

Realizing the need to provide the court with reasonable discretion, the lack of legal certainty on the above issues can prevent the owners of the disputed property, law enforcement agencies and the courts themselves from acting within the law and exercising their rights to the fullest extent.

4. The transfer of all disputed property to the management of ARMA (taking into account the threshold amounts for the initiation of claims and assets that must be transferred to management) should be ensured by the improvement of legislation regarding the handling of seized assets by empowering ARMA with the authority to store property, limiting the possibility of selling seized assets in disputes on declaration the assets as unjustified until the case is resolved on the merits. In addition, ensuring the procedural rights of the owner is associated with the preservation of the value of the asset, which is problematic without a qualitative improvement in the operational work of the Agency as a whole.

5. The law provides for the possibility of applying extended (equivalent) confiscation. That is in the case of destruction/alienation or decrease in the value of the disputed property, compensation for the lost value occurs at the expense of other property of the defendant. At the same time, the defendant, in accordance with Part 4 of Art. 290 Code of Civil Procedure of Ukraine, can be any other person. The foreclosure on his/her assets that are not deemed as unjustified, that is, related to an authorized person, may be considered as disproportionate. Indeed, given that the main element for the confiscation of an asset from a nominal owner is the connection of the disputed asset with an official, a third party who does not actually dispose of the disputed assets should not be held liable with his/her property for the actions of the official. On the other hand, such a provision can serve as a cover for officials from the risk of confiscation of their own assets due to the absence of additional property of the “nominees”. In this regard, if it is proven that the real owner of the asset is an official, the extended confiscation should primarily apply to his/her assets, and not to the assets of third parties.

Therefore, The Parliament needs to amend part 3 of Article 292 of the Civil Procedure Code of Ukraine, which should provide for the possibility of applying extended confiscation only to the assets of an official, but not to third parties.

In general, the institution of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets without a preliminary court conviction has many advantages and can significantly strengthen the system of combating corruption in Ukraine. At the same time, given the experience of foreign countries that have introduced such instruments, their effectiveness directly depends on the practice in the application of these provisions by both law enforcement agencies and courts. The broad discretionary power of the courts to determine “sufficiency” or “inadequacy” of the legitimacy of sources of income requires a high level of transparency and integrity to ensure fair and impartial enforcement of this legislation.